Shame as an affect, an emotion, or a feeling serves a critical purpose in the construction and maintenance of hegemonic power relations. Sara Ahmed defines it in her book The Cultural Politics of Emotion as an “intense and painful sensation that is bound up in how the self feels about itself (103).”

Neoliberalism has deepened the role of shame through the individuation of shame wherein the “apartness of the subject is intensified in the return of the gaze; apartness is felt in the moment of exposure to others, an exposure that is wounding (105).” The purpose of this essay is to examine the ways in which shame and other related negative affective responses are invoked in the poor and working classes as a tool of social control.

More specifically, I seek to reveal where and how poor and working class people are interpellated through shame and how shame functions as a coercive and, idyllically, a restorative social force, reproducing formations of power. I also examine the affects of the dominating class—disgust, pity, and contempt. I conclude with a brief exploration of the “refusal of shame,” restorative justice, and collective emotionality as potential modes of resistance for oppressed groups.

What is shame and how does it act on the body? Silvan S. Tompkins categorized shame as one of the primary “negative affects.” Shame is a complex, painful emotion caused by the consciousness that one has done something “bad”; that one has a moral shortcoming, or has engaged in an impropriety. Shame is not only a judgment we make about ourselves, but it is also dependent on our awareness of how we are perceived by others.

As Sartre writes, “I am ashamed of what I am. Shame therefore realizes an intimate relation of myself to myself,” but also, “I am ashamed of myself as I appear to the Other (222).” Shame is also closely related to, and often occurs concomitantly with, guilt and embarrassment. However, guilt is typically rooted, not in a judgment about one’s nature, but in a judgment about one’s behaviors. In other words, shame is about who we are, whereas guilt is about what we have done.

Because we often conceptualize ourselves as fixed subjects, moving through time, shame has a way of sticking to our being, whereas guilt, because it is attached to “bad” acts, is bound by temporality in a way shame is not. Further, shame carries a weight beyond embarrassment. For example, if I am walking down the street and someone walking towards me waves and I wave back, only to realize a second later they were waving at someone walking behind me, describing my affective state afterwards as “shamed” is probably an exaggeration.

These cloudy distinctions and the highly individualized experiences of shame, guilt, and embarrassment essentially make the case Sara Ahmed’s work on affective economies. She writes, “emotions work as a form of capital: affect does not reside positively in the sign or commodity, but is produced as an effect of its circulation (45).”

Ahmed, perhaps channeling Foucault a bit, posits that hate does not reside within the individual; it is economic and “circulates between signifies in relationships of difference and displacement (44).” The subject is just one point in this affective economy. Emotions do not rush to inhabit the subject and then wilt there; they circulate through that subject’s interactions with other subjects, with institutions, with the state, etc. The delineations between the affects themselves are murky, but “it is through emotions, or how we respond to objects and others, that surfaces or boundaries are made (10).”

As it circulates, shame acts upon the body in a variety of ways. It makes us want to become smaller, conceal ourselves, and, as Ahmed argues, “turn away from others who witness the shame. […] The subject, in turning away from another and back into itself, is consumed by a feeling of badness that cannot simply be given away or attributed to another (04).”

Most people are imbued with a certain level of “socialized shame,” wherein shame is experienced as simply being aware of how one’s body is moving through society. This kind of constant, low-level, intrinsic shame is culturally and socially relative and highly individualized. Fat, female, trans, disabled, racially-othered and otherwise non-conforming bodies are generally subject to more intense levels of shame in our society when compared to white, thin, cis, male, and able bodies. Alternatively, those that act without regard for socialized shame might be labeled as “feeling no shame” or “shameless.”shame,

Shame, like hate and love, according to Robert Solomon, is one of the few emotions “which are responsible for (as well as responsive to) the structures of moral responsibility which we impose upon our world (301).” Unlike anger, shame is rooted in a judgment about oneself, and unlike pride, it is unfavorable. In neoliberalism, shame operates as one of the primary tools of social control deployed against the poor and working classes.

We are interpellated by neoliberalism through shame in various ways: when we are unable to pay our mortgage or our rent; when bill collectors call; when we have to label ourselves as “indigent” to receive healthcare; or when our junky car stalls on the highway.

Class shame is a result of forcing the lower classes to take responsibility for things that were once seen as luck or fate. It serves the upper- and middle-classes by keeping the poor “in their place” and preventing them from taking advantage of the few social programs neoliberalism has not managed to decimate. It displaces the blame of poverty back onto the poor themselves. It reorders affective structures where positive, “good feeling” affects, just like resources and wealth, are funneled to the top, while the poor are left to twist in the wind, knowing that they must have failed, but never knowing exactly where they went wrong.

Shame is virtue for the poor in neoliberalism. Poor people are supposed to be ashamed when their poverty is made visible, even when visibility occurs by way of simply existing. The virtuous poor are ashamed that they cannot feed their children, that they use food stamps, that they have an EBT card, that they receive Medicare. Like a twisted postscript to modern Christian prosperity gospel, neoliberalism demands that the poor must prostrate themselves on the altar of individual responsibility and the free market in order to be made whole.

However, the poor can never be shamed enough. The bootstrap myth of neoliberalism relies on shame to be a prod to self-improvement. If one were adequately shamed for their failure to become a proper neoliberal subject, they would break out of poverty. It is in these cases that shame’s inverse, pride, is deployed against the poor.

Consider the following anecdote: “My mother had too much pride to apply for food stamps, even though we needed them.” Pride is closely related to shame as its inverse. It is a positive judgment of the self and our achievements. It is, as Schopenhauer writes, “an established conviction of one’s own paramount worth in some respect (222).”

In neoliberalism, the prideful poor person is aware that asking for help is shameful and the distinction between pride and shame becomes obfuscated. The poor person knows they need assistance, yet also know that asking for help is shameful, thus the statements “my mother had too much pride to apply for food stamps” and “my mother was too ashamed to ask for assistance” come to mean the same thing.

Despite this fact, the language of pride and shame is still used to pit the good prideful, stoic, socially useful poor person against the bad “shameless,” parasitic poor person. This shows the ways in which affective responses are deployed against the lower classes through the lower classes. For instance, neoliberalism, in its emphasis on competition, pits different groups of lower classes against one another for jobs and access to wealth and stability. Thus, in the United States, the lower classes (and middle-class) often view one another as foes, competing for the same resources, rather than rightly viewing the bourgeoisie as the wealth-hoarders, economic oppressors, and divisive rhetoric spinners.

Of course the dominant upper and middle-class are not without their own affects. After all, shame is partially dependent on the perceived or anticipated affective response of the witnesses to the shame. I am only going to focus on a few of these potential affective responses. First, Ahmed points to “disgust” as one of shame’s corollaries. However, shame does not originate in the shamed. That is, it does not well up for no reason.

For example: A man is waiting behind a woman in a checkout line. The woman is using an EBT card to pay. The cashier loudly tells her that she has thirty dollars on her card and it is not enough to cover the total. The man behind her looks at the woman; she has on Nikes and has an iPhone. Her nails are done. He looks at her items, and judges that they are not sufficiently modest. He rolls his eyes and sighs loudly, disgusted at this apparent abuse of the system and his tax dollars.

As the woman sorts through her items, trying to determine what to put back, she notices his gaze and his sigh and feels deeply ashamed. The man notices this, sees her blush, and feels justified. Her shame, for him, becomes a confirmation, an acknowledgment, that her need is not genuine. Ahmed writes, “In disgust, the subject [in this case, the man] may be temporarily ‘filled up’ by something bad, but the ‘badness’ gets expelled and sticks to the bodies of others (104).”

When the man sighs, he expels his disgust and generally goes on with his life without much thought. The woman recognized this, converted it into shame, and used it to make a judgment about herself; one that sticks to her being and continually informs her relationship to herself, the man, and the world around her.

By contrast, pity often serves as the morally righteous hegemonic anecdote to disgust (note here I did not bring in compassion or sympathy. I believe that these emotions exist, not within the neoliberal affective economy, but outside it; in spite of it). Pity, says Solomon, is compassion “mixed with glee” and conveys a “better him than me” (281) meaning.

Pity is condescending and, thus, is defined, in part, by its superiority. This is why “I pity you” is such a biting insult, “implying that you are at least an inferior human if not subhuman and depraved (281).” Pity is enacted through the same affective routes as disgust, as we’ll see later, contempt. If the man in the earlier scenario had shown pity rather than disgust, he might have offered to pay for the woman’s items, refusing her attempts to pay him back, and then post about it on Facebook to show his friends what a great person he is.

Of course, individual (and even collective) acts pity are never enough to create real change for the poor. Thus, pity is actually a self-serving affect. It both reinforces the humanity of the giver and the alterity and dehumanization of the poor.

Ahmed writes that, “Hate is always hatred of something or somebody, although that something or somebody does not necessarily pre-exist the notion (49).” Neoliberalism, in its emphasis on individual responsibility enacted through its “financialization of everything,” places little to no value on the poor body. They are viewed as “drains on the economy,” “welfare queens,” “trailer trash,” etc.

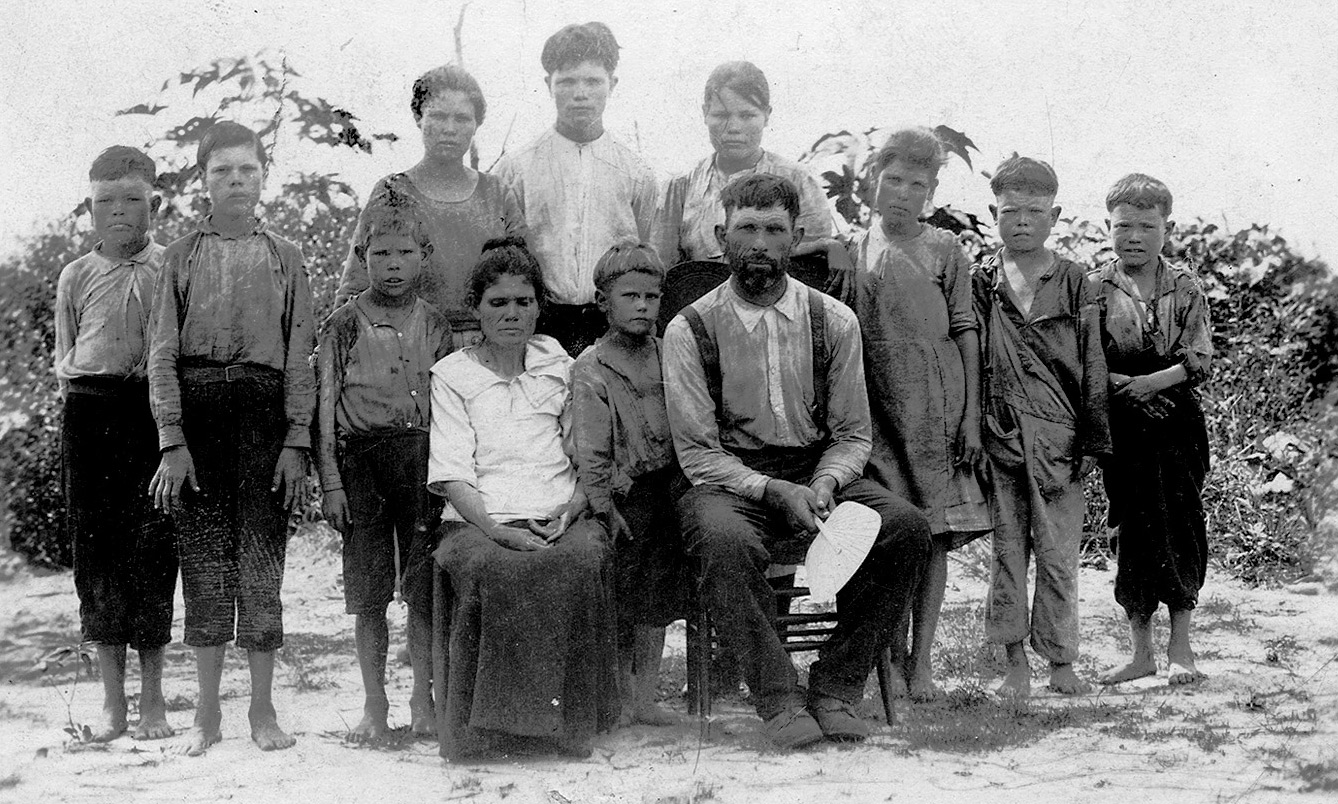

As Dorothy Allison writes in her piece “A Question of Class”, “We were the they everyone talks about—the ungrateful poor […] I did not know who I was, only that I did not want to be they, the ones who are destroyed or dismissed to make the “real” people, the important people, feel safer (112).”

Ahmed shines light on this dichotomy, saying, “Hatred may also work as a form of investment; it endows a particular other with meaning or power boy locating them as a member of a group (49).” Businessmen, (proper) homeowners, and other “productive members of society,” stand in contrast to the hated class.

While a case could be made for the “hatred” of the poor, contempt is a more accurate descriptor for how the middle and upper-classes view the poor within neoliberalism. Contempt is the hegemonic inverse of shame: a severe judgment about someone else’s nature or being and it sticks to bodies. Contempt, according to Solomon, is “morally tinged, (but double-edged with the suggestion that the person is incapable of morality) (234).”

Like pity, contempt implies superiority. The contempt of the poor is captured in narratives that describe them as lazy, stupid, worthless, and “as drains on the system.” In an anti-Trump essay in the National Review columnist Kevin Williamson argued that the white working class had “failed themselves” and that “the truth about these dysfunctional, downscale communities is that they deserved to die.”

Williamson, like many in the dominant classes, is skilled at seamlessly braiding together a group’s economic value with their social worth. Only those that have proven they are worth assistance are deserving of it. However, the only ones that have seemingly ever met this impossibly high bar are the ones that created the financial crisis: the banks, the CEOs, and the upper class.

Of course, this narrative also blames the poor for the economy’s ills, charging them with having significantly more power than they could ever have in neoliberalism. Meanwhile, the middle-class clings to their contempt of the poor, hoping that it will distinguish them for what they could be close to becoming. Thus, contempt reveals its defensive characteristics; it “dramatizes”, writes Solomon, and projects outwards one’s own standards “to make oneself appear, by way of contrast, superior, powerful, and noble (235).”

Shame intrinsically lends legitimacy to the structure of authority that generates it. When we feel shame for our class status, our debt, when we need financial help; or—extrapolating outward to the ideological—when we feel ashamed for needing a day off, for “being lazy”; when we fail to maximize our precious, commodified time; and, finally, when our bodies breakdown from labor and we need someone to take care of us; we are legitimizing neoliberalism through the internalization and enactment of its ideological and repressive ends.

Perhaps, then, the first and primary mode of resistance for the poor (and other socially shamed bodies) should be the refusal of shame; denying neoliberalism and its ideologies the satisfaction of shaming us for living without shame, taking without feeling guilty, giving without communicating pity; operating shamelessly on the assumption that everyone deserves food, shelter, healthcare, and nice things independent of their “social value.”

The beauty in this strategy is it absolutely enrages those that hold fast to neoliberal values when they are flagrantly violated. This is why the myth of the welfare queen persists; why the image of “trailer trash” with the flat screen outside and the “thug” with the gold chain and tricked out car remains a cultural touchstone. If the narrative is “poor people should not have nice things because reasons x, y, and z,” and x, y, and z are based on a fundamentally corrupt ideological system (in this case, neoliberalism) that ties an individuals social value and to their economic utility, then that narrative needs to be dismantled.

Ahmed writes, “to transform bad feeling into good feeling (hatred into love, indifference into sympathy, shame into pride, despair into hope) is not necessary to repair the costs of injustice. Indeed, this conversion can repeat the forms of violence it seeks to redress, as it can sustain the distinction between the subject and object of feeling (193).” Restorative justice “allows emotions to return to the scene of justice (197).”

Originating in the criminal justice system, restorative justice forces perpetrators of crimes against other people to feel the material consequences of their actions; they meet the victim or the victim’s family and the victims are allowed to emote their anger, fear, and suffering. Through this process, the perpetrator is enfolded back into society, where they are made to “face the emotional consequences of the crime (198).”

Ideally, they feel and express remorse. They apologize to the victims, make some kind of reparation, and the victim is made more whole through this exchange. With this in mind, perhaps we could force restorative justice through the act of shaming of those people who are destroying the environment, making astronomical profits, and boosting CEO pay, while exploiting workers through the systematic and collective shaming of those individuals that have long deployed shame as an ideological tool of control.

As Oleg Komlik writes in his piece on resistance strategies within neoliberalism, “[we must] publicly name and shame specific actors and organizations (in politics, in the academia, in the press and everywhere) embracing neoliberal logics and promoting ‘profit above all’ practices, directly disgrace them and continuously condemn them.”

Ahmed writes in the conclusion to The Cultural Politics of Emotion, “anger against injustice can move subjects into a different relation to the world, including a different relation to the object of one’s critique (201).” The anger that motivates with the shaming of corporations and individuals they are comprised of is, itself, a mode of “feeling better.”

Though they are negative, emotions like anger and rage can also be enabling or creative, often through the motivating collectivity of affect (i.e. collective emotionality through shared experiences or shared identity). But, “the emotional struggles against injustice are not about finding good or bad feelings, and then expressing them. Rather, they are about how we are moved by feelings into a different relation to the norms that we wish to contest, or the wounds we wish to heal (201).”

Of course, it will not be as easy as it is stated here. Neoliberalism’s tenure has made the rich in the U.S. far more skilled in refusing shame than the poor. However, it is worth it to speak out against the worship of money, and fairytales involving “invisible hands” and trickle-down wealth, even if the only success is recuperating what is lost of the self within the affective economy of shame.

Samantha Pinson Wrisley is a PhD student in the Department for Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Emory University. She also holds an MA in Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies from Georgia State University (2017) and a BS in Psychology and a BA in Women’s Studies form the University of Georgia (2014). Samantha’s research uses affect theory, theory of emotion, and feminist theory to understand the affective, discursive, and social contours of “gender reactionary” movements (e.g., “Incel”).