The following is the first of a two-part series.

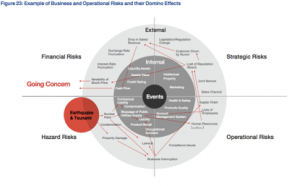

As this clip from the 7th Edition of The World Economic Forum (Davos) Global Risks Report 2012 illustrates, the event as catastrophic emergency has become the point of application for the biopower wielded by contemporary governance both local and global.

But the event is a trope common also, however, to revolutionary philosophers (Badiou), deconstructionists (Derrida), genealogists (Foucault), philosophical iconoclasts (Agamben) and Christian theologians (the Christ event), as it is to security managers, risk analysts, financial gurus (financial tsunamis, blank as well as black swans), complexity

(http://www.weforum.org/reports/global-risks-2012-seventh-edition) (I have Bradley Evans to thank for drawing my attention to this report.)

scientists, and global governors (icons that Agamben seeks to ‘take down’ include some of his own most seminal influences: Heidegger, Derrida and Foucault).

There is no space, here, for me to go into this intriguing conjunction. But it is this very conjunction which lies behind the motivation of our conference here this weekend, and I thank you for the platform it gives me to reflect on the ‘thinking about thinking’ traversing all of these domains and that is so intimately bound up with their articulation and impacts.

It is therefore important for me to note the conjunction if only in passing because it so clearly gestures towards that wider field of formation to which the rules of truth as well as the truths of rule that they share, and which are in turn so deeply lodged in the thought and practices of our age, certain aspects of which I am going to address in this essay.

In any event – I will begin by expressing a truth fundamentally to all evental thinking – and that is this: an event is never that which simply happens. The time of the event, however the event is conceived, is not only a time of rupture, it is a conception of time as ruptured and rupturing. It is a time that strictly accords with the etymology of the Greek word καταστροφή (katastrophḗ) from καταστρέφω (katastréphō, “I overturn”), from κατά (katá, “down, against”) + στρέφω (stréphō, “I turn”).

Such a rupture, or catastrophic overturning, spaces time out. It creates an interval which interim, as Alain Badiou observed, “is a space of consequences.” The event is eschatologically structured, then, and where there is an eschaton there will always be a katechon; a katechon whose task, as St Paul enigmatically first taught in Thessalonians 2, is to hold back the event to ensure that when it takes place it does so in an approved eschatological fashion; not subverted by a false Messiah, or by the machinations of an Anti-Christ.

The evental eschaton of revealed religion, its catastrophe – which catastrophe like all catastrophes combines the promise of renewal within the context of mortal danger – thus signaled the threshold obtaining onto-theologically between the eternal and the mortal, the transcendental and the immanent, the sacred and the profane.

Ultimately, it is the ontico-ontological difference which is the source of eschatological thought and practice. The space of consequences thus opened up, to employ Badiou’s felicitous expression again, was one in which the rule of truth of revealed religion became acted out as the truth of rule of its redemptively enframed problematisation of government and politics. Here, the very temporal field of formation in which the problematisation of politics, government and rule was staged was that provided by time as salvation history.

Human beings were mortal, but, as ens creatum, their finitude was a soteriological finitude integrally bound up with the manifestation of the eternal presence of an all powerful creator God. Christianity’s claimed incarnation of that God in Jesus Christ further promised redemption and everlasting life for all mankind, conditional on a final judgment to be conducted at the end of days when Christ was prophesized to come again, and the world of human beings, together with the entire universe of God’s creation, would return to the eternal presence from which it was said to have first issued in an act of divine will.

The manifestation of this rule of truth – knowledge of it confessed and formulated over millennia by Christian theology, political theology and subsequently also in the natural philosophy, or scientitia, of the Scholastics – found its expression also, of course, in the truths of Christian rule. It is in this sense, then, that human beings were regarded as sub specie aeternitatis. That is to say their very finite appearance read as a manifestation of the truth of the eternal God. Ultimately, their government both secular and religious – the very differentiation of the secular from the religious being the theological work of Christian differentiation from St. Augustine onwards – revolved around it as well.

Not so with modern finitude, to which I therefore give a different name, that of factical finitude. Here, things do not exist sub specie aeternitatis. They exist ad infinitum. Here, time is not soteriological. History is not salvation history. There is, simply (factically), an infinity of finite things. And infinity is very definitely not eternity. If eternity is the temporal cause and ground of finite things conceived faithfully in terms of sub specie aeternitatis, infinity is simply the correlate of the finite conceived positivistically, and, in contemporary terms of post Cantorean mathematics, of an infinity of infinities.

The very positivity of modern science – premised upon the infinity of finitely knowable things – could not be conceived or pursued without the correlation of finitude with and through infinity. It is against that posited infinity of finitely knowable things that the positivistic and material properties of finite entities are differentiated, measured and mapped-out.

Whereas politics, government and rule problematised according to the rules of truth and truths of rule of soteriological finitude is, consequently, thought theologico-politically, its models of catastrophe drawn from the Fall, the war in heaven and earth against Satan, and, ultimately, the Christian eschaton – such is not the case with the problematisation of modern politics, government and rule. The rules of truth and truths of rule of modern problematisations of politics, government and rule are instead those posed by the spatio-temporal order of factical finitude.

Whereas the mortal politics, government and rule of Christianity’s redemptively inspired soteriological finitude was cast as a necessary but limited human expediency, awaiting the pleroma or fulfillment of God’s plan, such, again, was not the case with the problematisation of politics, government and rule obtaining under the terms and conditions of factical finitude. Here rules of truth and truths of rule are very differently posed and derived. Thus, politics, as a performative field of formation and self-actualization, gets problematised very differently.

According to the rules of truth of factical finitude, then, the first truth of rule is that politics concerns the infinite government of finite things, that is to say the infinite government of things that, by definition, will end, whereas the task of governing them never will. That they end, and how they end, is the catastrophe around which modern politics, government and rule revolves. As with revealed religion, so also the catastrophes of modern politics, government and rule are the locus not only of mortal danger, but also of (a differently conceived articulated and pursued) renewal.

In consequence, the second truth of rule of the rule of truth of factical finitude is that since everything is impermanent – a matter of an infinity of comings and goings, of the deaths as well as the births, that must make way for the new – the infinite government of finite things revolves less around the business of the ends of which finite entities may be said, in Aristotelian or perhaps Hegelian fashion, to be comprised, than the business of their endings.

In as much as the formulation of the modern task of politics, government and rule is, therefore, construed foundationally as keeping formless, that is to say lawless, chaos at bay, deferring the end that nonetheless defines all finite entities, or ordering the execution of those that threaten and offend against the prevailing order of things, the task of politics, government and rule is foundationally considered to be that of katechontic restraint in the exercise of which lawful killing is not simply licensed but vitally necessary.

One defining aporia of this, our prevailing problematisation of politics, government and rule, is that it offers no formula capable of specifying how much killing is enough to exercise the katechontic restraint required of it. When asked how much killing is enough – a question which of course ramifies into who will be killed or, in biopolitical terms, systematically exposed to mortal danger for the good of Life politics itself – the answer is more.

Hence, foundationally speaking, modern politics is a politics of security – indeed an infinite securitization of finite things, which securitization is, of course, a politics of war masquerading as a politics of peace – before it is a politics of anything else. Thus, if you desire a different politics, you have to posit a different order to time, and specifically if you are not part of one of the communities of belief of revealed religion, to factical temporality than the one that has predominated thus far in modern history and political thought, which thought has of course always revolved around this its catastrophe of thought.

Factical finitude is, of course, saturated with endings and a profoundly imminent as well as immanent sense of endings. But the end of factical finitude is not the ending conceived in the texts and sayings, as well as theology. of Christian redemption, a faith progressively policed, its liturgies and practices regulated via the rule of an imperial Church, which rule is operationalised governmentally though the mechanisms of pastoral power.

In other words, the infinity of finite things knows no eschatology in the traditional religious sense of an ending to time combined with the advent of a different, an eternal, time to come. There have, of course, been many modern eschatologically inspired political ideologies and movements. The very understanding of the temporal enframing of the modern, possesses no mechanism, however, not even a telos to History, by which all finite things may be securely gathered together and exalted before being assigned to their eternal end.

Among other questions, the question of hope as well as truth arises here. However many answers may be offered to it, hope is not itself an answer but a problematic, one said in many ways, open to many different kinds of interpretation including also the one that states bluntly that there is no hope, and that the narrative of human existence is consequently a tragedy not a pilgrimage.

The question of hope nonetheless remains central to all modern rules of truth and their correlate truths of rule. It is an integral part of the very decorum that is required of modern political subjects of truth. Not to offer hope is as sinful in modern terms as the denial of salvation was in religious terms. The confession of hope is simply that – a necessary aspect of the decorum we are obliged, perfomatively, to act out as subjects of modern truths.

For people of faith, factical finitude is the catastrophe in as much as it offers no hope and denigrates the one offered by revealed religion. For people of no such faith, soteriological finitude has long been the catastrophe, serving the interests of domination, mystification and rule more than the interests of truth, even its own truths. Both abhor the nihilism that refuses to be governed by the decorum of hope. But even in Nietzsche the problematic of hope, heavily reformulated, remains a necessary trope.

For modern finitudinal accounts of time, then, the evental eschaton functions to punctuate the infinity of finitudinal orders instead. Here Badiou’s space of consequences takes governmental as well as revolutionary form. One of the concerns of my work long focused on the probematization and organization of government revolving around the event as the catastrophic emergency of Life understood as complex emergence that now dominates the biopolitical account of Life prevailing throughout the societies of the North Atlantic Basin.

At this point I want to foreground a point operating implicitly in my talk, making it explicit in order to move towards delivering on the rash promises made in my title, segueing to an argument which, first positing the radical ineffectiveness of modern critique, substitutes for it the allied issues of refusal and resistance in terms of insurrection and rebellion, the courage of truth and political spirituality.

This is a very long stretch I admit. It is still a raw chain of argument, one deeply inspired by Foucault’s last lectures, and his newspaper reports from Tehran at the height of the insurrection against the Shah in which he used the term ‘political spirituality’ for the first and only time. Turbulent and raw as this chain of argument no doubt is, then, I want to try it out here for the first time.

I start then by emphasizing that when I employ the term catastrophe of thought I do so in two ways, of which the second is the one most interesting to me and the more pertinent to my argument about the time of this reformulated catastrophe – the time that remains – in which we moderns live. Human beings have always lived in catastrophic times of course.

The point is the nature of the catastrophe in which they describe themselves as living: and, more to the point for a political thinker or one who tries to think politically, the material and historical fields of problematisation from whose conditions of possibility they derive their conditions of operability as well in the form of truths of rule as well as rules of truth.

There are in the first instance then, as I have just been discussing, the catastrophes around which political and religious thought in our tradition revolves. But there is also a catastrophe integral to thought. Something that continuously overturns thought – the kata-strophe of thought itself. It is this catastrophe that I want to explore now. It needs to be approached carefully. But, given the time and the occasion, rather than keep it secret from you, while I do the intellectual labor of qualification and elaboration it requires. I will simply venture a blunt account of it for you.

Thought is a vehicle for truth telling. Truth finds its manifestation among many other means, in thought. Thought is not the only way in which truth is manifested, then, but it is one way. There are many other ways of manifesting truth, just as there are many kinds of truth tellers. But thought has always claimed, and been accorded, a privileged position in the playing out of the truth games characteristic of our civilization. Truth has a history. It is said in many ways. In Foucault’s terms thought is, then, a veridical apparatus concerned with manifesting truth, a manifesting that, however much it includes radically also exceeds knowledge and apparatuses of knowing.

Michael Dillon is a professor emeritus at Lancaster University with a focus on politics, philosophy, and religion.