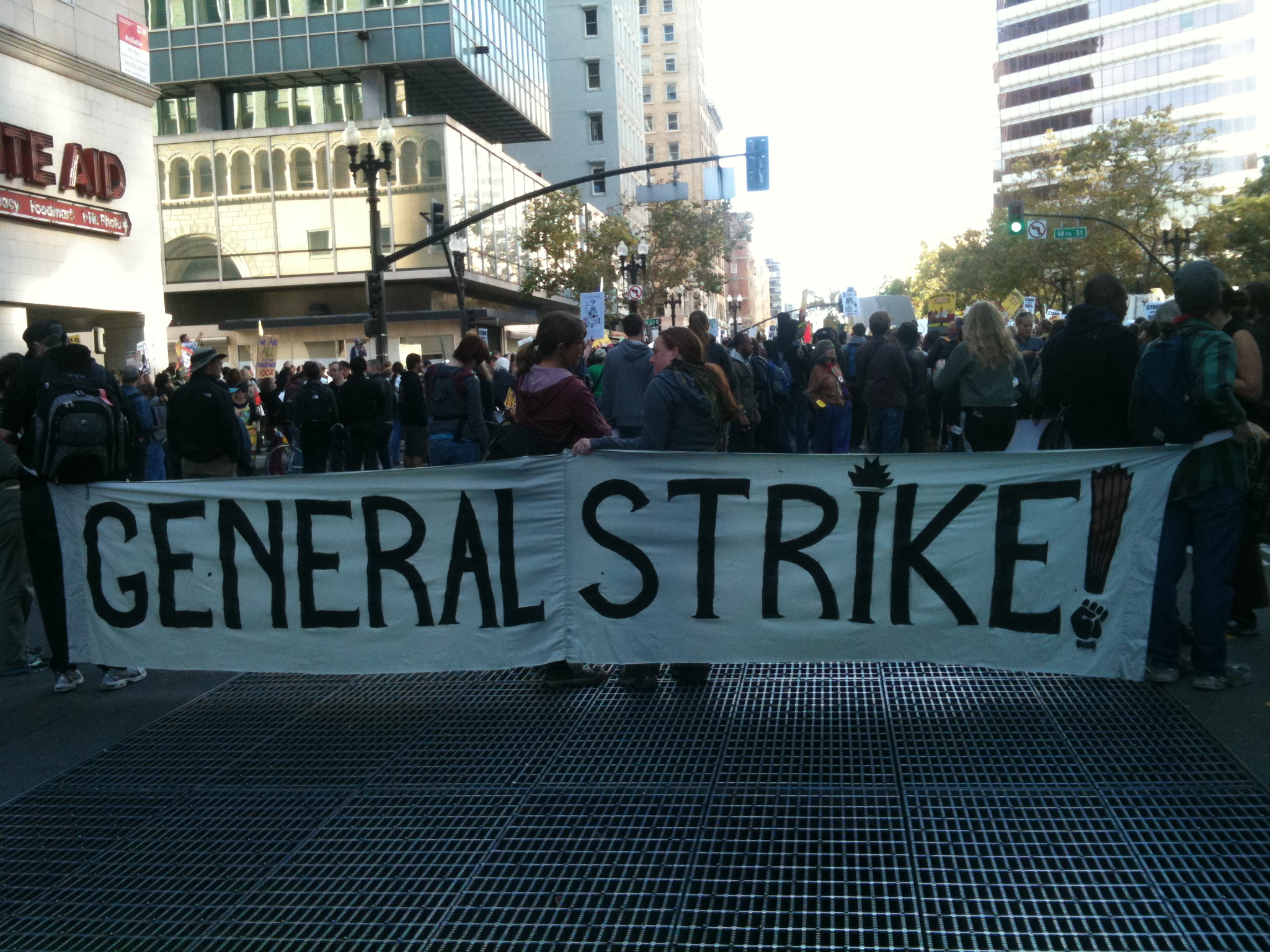

The crisis of the global, neoliberal order has now entered an acute phase, distinguished by what has become de facto what radical agitators and insurrectionists have dreamed about since the high water mark of the industrial era – a general strike.

The “strike” has neither been fomented from the grass roots nor implemented with any kind of agenda or strategy. From airline pilots to restaurant servers to dock workers, what are popularly and often euphemistically referred to as “labor shortages” have put the global economy at large, and the American economy in particular, in an ever tightening vise grip.

The result has been shortages of basic goods and accelerating inflation of the kind not experienced since the 1970s. A headline in The Atlantic in early October entitled “America Running Out of Everything” eerily mimicked the cover of Newsweek on November 19, 1973 at the height of the Arab oil embargo and the start of what would become a decade of economic upheaval highlighted by the unprecedented and seemingly intractable phenomenon known at the time as “stagflation”.

A slithering slew of explanations for what is going have been offered by opinionators from the aging of the world population to a postulated anti-work ethic of Gen Z employees. And course the long-term impact of Covid to the lack of child care to misalignments between what business are used to demanding and what workers are increasingly willing, or unwilling, to provide factors into the equation.

The trendline, however, no matter what the causal connectors turn out to be, is toward a slow, lumbering, but inexorable breakdown of the system. It has all the makings of a revolution without revolution, a radical transformation without any discernible transformative agents to initiate or propel it.

A perhaps overused descriptor would be “apocalyptic”. But the original Greek term apokalypsis, from which the English version is derived, does not so much connote a violent breakdown so much as a breakthrough, a sudden manifestation that clears away of all the detritus and distractions that have inhibited the mind hitherto from focusing on what is truly true, what ultimately matters.

That is what in an important sense may be going on these days. As an in-depth analysis of what has come to be dubbed “The Great Resignation”, Inc. magazine observed in its trademark bland yet magisterial manner that “those fleeing what might be viewed as perfectly good jobs are simply choosing to put themselves first for a change.” It added: “More importantly, workers simply want to be recognized.” They “also want to work for companies they can be proud of, that are involved in their communities and that take a stand for things that they believe matter.”

That sentiment may be more of the all-too-familiar educated, elite idealism that once saturated the workplace attitudes, not to mention the political values, of millennials more than a decade ago and now has morphed into a kind of clueless sclerosis of thinking, as well as a toxic fanaticism in numerous instances, that has come to be labelled “wokeness”. Yet it also reveals a disturbing disconnect between the power and wealth of the “knowledge classes,” about which I have written extensively, and the quotidian labor that makes it possible.

As the celebrated French economist Thomas Piketty in his most recent book opines, “history shows that inequality is essentially ideological and political, not economic or technological.” (11-12). What does he mean by that statement? In an earlier work entitled The Economics of Inequality, Piketty re-assesses a variety of standard economic theories in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, including neo-Marxist models, that ferret out the intricate web of connections between capital and labor in current systems of production. Piketty concludes that the rise in inequality since the 1970s has arisen from commanding shifts in the distribution of “human capital.”

Piketty writes that “during the first phase of the Industrial Revolution…wage inequality increased as industry demanded more and more skilled labor and large numbers of unskilled laborers streamed in from the countryside. From the end of the nineteenth century to the 1970s, wage inequality decreased in all the developed countries.”(121).

However, with the advent in the late 1960s of what political economists have dubbed “de-industrialization”, the presumed differential between labor and capital, which historically has been propelled by discrepancies between different shares of ownership in the means of production, the engines of inequality began incrementally to be fueled by corresponding disproportions between varying forms of “human capital”. Piketty calls this maldistribution “human capital inequity”, which originates largely but not entirely from diverging educational attainments. In other words, economic efficiencies and class inequities go hand in hand.

In addition, because of the centrality of the educational component in both “capital formation” and the soaring valuation of what Maurizzio Lazzarato has termed “immaterial labor”, present day “capitalism” rests on an economy of infinitely generated signifying processes. It is semiotic. As Felix Guattari famously noted:

Capital is not an abstract category: it is a semiotic operator at the service of specific social formations. Its function is to record, balance, regulate and overcode the power formations inherent to developed industrial societies, power relations and the fluxes that make up the planet’s overall economic powers. One can find systems of capitalization of power in the most archaic societies. These powers can assume multiple forms: capital of prestige, capital of magical power embodied in an individual, a lineage, an ethnic group.(244)

The familiar Marxist notion of capital as private, concentrated ownership of the means of production in the age of digital media, digitized finance, blockchains, and crypto-currency thus becomes utterly obsolete. All capital is “human capital”, or what Gary Genosko names “semiocapital”, because it boils down to the generativity of the signifying apparatus itself, what Jean Baudrillard referred to as “procession of simulacra”. It is tantamount to the potential for immanent schemas of reciprocal referentiality not only to reproduce, but rapidly transform themselves. “Intelligence” in the sense that Bernard Stiegler has in mind when he talks about the transition from tool-making to the “grammatization” of culture suffuses everything and, at least from the theoretical perspective, seems to permeate the world of manufactures.

If it is signs and significations that mold all capital as human capital in the current age, then all culture wars are really class wars. The “capitalists” are the cosmopolitan knowledge and cultural elites, who do not technically possess the systems of production, yet through their domination of the discursive regimens and symbolic machineries that signal legitimacy and authority are able to arrogate for themselves a ghostly, though unassailable sovereignty that carries over into what classically is understood as the economic sphere. That is the very insight the Frankfurt School acquired between the World Wars in their discovery that, contrary to orthodox Marxism, capitalism is inseparable from its own “culture industry”.

For Piketty, the every complexifying growth of a global economy dependent on human capital inequities, which in turn mirror educational disadvantages and widening discrepancies in the ability to manipulate the very sign-operations that produce both prestige and wealth, mean that dysfunctions, interruptions, and breakdowns are ever more likely to arise. As Piketty puts it in economistic jargon, “the elasticity of the supply of human capital (defined in an analogous way to the elasticity of the supply of capital) is very high” (135). And such elasticity inexorably leads to deepening income inequalities, so long as the efficiencies of old-fashion material labor remain in place.

But a funny thing happened in the historical saunter toward a progressive neoliberal arcadia of machine-based productivity, expanding custodial or “biopolitical” management of the lives and livelihoods of the less educated working classes, and an airy-fairy appreciation of all asset classes through the promiscuous play of digital simulacra in an investment universe no longer tethered to the actual output of goods and services. It was the Covid-19 pandemic.

Following long-nurtured Keynesian fiscal prudence and protocols, fiscal policy-makers goosed the volume of money in circulation to sustain both businesses and quarantined populations throughout the pandemic. As the latest surge of the pandemic eased, consumers throughout much of the developed world acquired excess savings which were not spent incommensurately on goods rather than services. Labor shortages, supply chain tangles, and runaway energy and transportation costs, an appreciable percentage of which have been fostered by tightening government policies aimed at reducing carbon emissions have all converged to drive up the price of both commodities and finished products, creating a negative feedback loop that exacerbates an already deteriorating situation.

Fears concerning the safety of the workplace with seemingly unending cycles of virus upsurges, state-mandated lockdowns, and festering “pandemic fatigue” have seriously attenuated the size of the workforce in many countries, which in light of the uncoupling of economic production with demand has seeded what is beginning to look like mounting inflationary pressures of a global magnitude. But lifestyle choices and personal re-appraisals of the meaning of work have also played a crucial role. In recent weeks the media has been awash with various anecdotal and armchair analyses as well as more data-infused styles of punditry about the causes of the “Great Resignation”. Besides a vast array of randomized speculation referenced earlier, assignment of blame for the sudden dearth of labor force participation has run the gamut from a drop in families with dual wage earners to employee fastidiousness about what they consider acceptable jobs to lack of remote job options.

But Gallup polling has found the The Great Resignation actually needs to be reconceived as “The Great Discontent”. Gallup found that “the pandemic changed the way people work and how they view work. Many are reflecting on what a quality job feels like, and nearly half are willing to quit to find one.” What is egregiously absent, however, in all the polling and punditry is a more penetrating structural diagnosis concerning how the makeover of global capitalism in recent decades has come to its own unique and perilous pass that corresponds, broadly speaking, to what Marx himself denoted as a “crisis”.

Piketty has a rather bland take on the crisis that masks its more congenital dynamics. He writes:

At the global level, the share of the world’s poorest 50% of the world’s population has clearly increased from 7% of total world income in 1980 to around 9% in 2020, thanks to the growth of emerging countries. However, this progress must be put into perspective, as the share of the world’s richest 10% has remained stable at around 53%, and that of the richest 1% has risen from 17% to 20% of total world income. The losers are the middle and working classes of the North, which is fueling the rejection of globalization. (323)

The Great Resignation is also a Great Refusal of “the losers”, no matter how one bowdlerizes or sanitizes it, to take part, even if it is for now merely a vast tableau of privatized, ad hoc gestures in the aftermath of the pandemic, to take part in the exploitation of human capital that has functioned as the lifeblood and arterial meshwork of the neoliberal order. Covid forced mass withdrawals from the labor markets, but during the time of these copious and far-flung employee “sabbaticals” a new sensibility seemed, like an arabesque of spring wildflowers, to be peeking out across the pandemic-ravaged workscape.

As a modicum of data attained so far shows, the Great Refusal has been concentrated among previously underpaid and expendable service and menial worker, together with a mish-mash of overburdened and poorly paid professionals that include teachers and lower-level health care personnel. It is not a co-ordinated “general strike” with the intent of collapsing the current political system in the romanticized sense that radicals and revolutionaries from Georges Sorel to W.E.B. Dubois have framed it. But, despite its indeterminate motivations as well as its lack of visible leaders along with its amorphous makeup, it displays many of the same causes and effects.

As former U.S. Labor Secretary Robert Reich puts it,

You might say workers have declared a national general strike until they get better pay and improved working conditions. No one calls it a general strike. But in its own disorganized way it’s related to the organized strikes breaking out across the land – Hollywood TV and film crews, John Deere workers, Alabama coal miners, Nabisco workers, Kellogg workers, nurses in California, healthcare workers in Buffalo.

Pundits in the mainstream press, including the mouthpieces of the international business establishment, have gone out of their way and quoted profligately from their own harems of “experts” to convince us that the trend, like inflation, supposedly is but a fleeting distemper. But the comfortable neoliberal world picture is cracking everywhere at the seams because of its own structural defects from which academic grand theory, addicted to social (pseudo)-science, digital utopian fantasies, and the intellectual idolatry that confuses truth with quantification, habitually averts its gaze.

The Great Resignation, or Great Refusal, the Great General Strike That Isn’t, or whatever we may name it, whether deliberate or desperate, is not only cry for recognition in the spirit of Hegel’s master-slave dialectic, but a demand for dignity. Like all revolutions, it starts with something unexpected and inconspicuous, such as Rosa Parks’ refusal to go to the back of the bus or the anonymous Tunisian vendor whose self-immolation sparked the Arab Spring. But on this occasion it is not a singular incident, but an invisible and rhizomic labyrinth of personal decisions.

Like the Corona-virus pandemic that occasioned it, is origin seems indecipherable. Yet its impact is tremendous. If in the Marxist universe inert capital gobbles up living labor, in the post-Communist neoliberal land of Oz the transformation of labor into human capital secretly means that “capital” is capable of revolt. The pandemic is the little dog that has pulled back the curtain, and the next decades promises to unleash the tornado that blows away the land of Oz to which the captains of the Moloch-like digital industrial complex, the Babylon on the virtual seven hills they proudly call the Metaverse, have seduced us all these years into selling our precious souls.

Carl Raschke is Professor of Philosophy of Religion at the University of Denver, specializing in Continental philosophy, art theory, the philosophy of religion and the theory of religion. He is an internationally known writer and academic, who has authored numerous books and hundreds of articles on topics ranging from postmodernism to popular religion and culture to technology and society. Recent books include Postmodern Theology: A Biopic(Cascade Books, 2017), Critical Theology: An Agenda for an Age of Global Crisis(IVP Academic, 2016), Force of God: Political Theology and the Crisis of Liberal Democracy (Columbia University Press, 2015) and The Revolution in Religious Theory: Toward a Semiotics of the Event (University of Virginia Press, 2012). His newest book is entitled Neoliberalism and Political Theology: From Kant to Identity Politics, (Edinburgh University Press, 2019). He is also Senior Consulting Editor for The New Polis.