The following is the first of a two-part series. The article originally appeared in The Journal for Cultural and Religious Theory 22:1.

Introduction

As the world becomes increasingly globalized the colonizing influence of western nations have repeatedly proven to be a precursor to global movements. One of the specific areas wherein colonial influence can be seen is that of gender roles. By observing the social and political development of the feminism movement as a human rights issue alongside the more recently developing LGBT+ movement, we see the development of a new panarchial influence beginning in the west.

Colonial influence has not been heteronormative since the acceptance of the women’s rights movement. Today we are seeing the effects of yet another development in western ideology with the potential to affect a globalized people in much the same way as the women’s rights movement. This panarchial-normative influence not only transcends the binary gender role formatting in the public and private sphere, but also allows space for those outside of the gender binary to be included in an accepting and affirming social environment.

Heteronormative Beginnings

Heteronormativity, as first coined by Michael Warner in 1991, has been ingrained in the mindset of the polis throughout history, conferring social power and privilege to the exclusions of LGBT+ individuals.[1] Brandon Robinson describes heteronormativity as “a hegemonic system of norms, discourses, and practices that constructs heterosexuality as natural and superior to all other expressions of sexuality.”[2] This retroactive perspective draws attention to the invisible gorilla[3] of heteronormativity by illuminating the historical discrimination of sexual minorities found in most social institutions including religion, family, education, media, law, and state.

The result of this heteronormative framework has led to widespread disadvantages imposed on LGBT+ individuals. Between 2016 and 2020 the rate of homelessness in LGBT+ populations increased by 88% and the number without shelter rose by 113%.[4] LGBT+ individuals experience barriers in finding adequate healthcare. Trans and non-binary people in particular report negative experiences with healthcare providers.[5] Many insurance policies do not cover LGBT+ needs to the extent that they cover heterosexual needs.[6] Even LGBT+ students report discrimination and poor health service at 4.5 times the rate of cis-heterosexual students.[7] Instances of disadvantage and discrimination are widespread throughout the world and its history, however, statistics representing such disparities are scarce and often attributed to a lack of recognition amongst the scholarly elite until recent years.

The Women’s Rights Movement

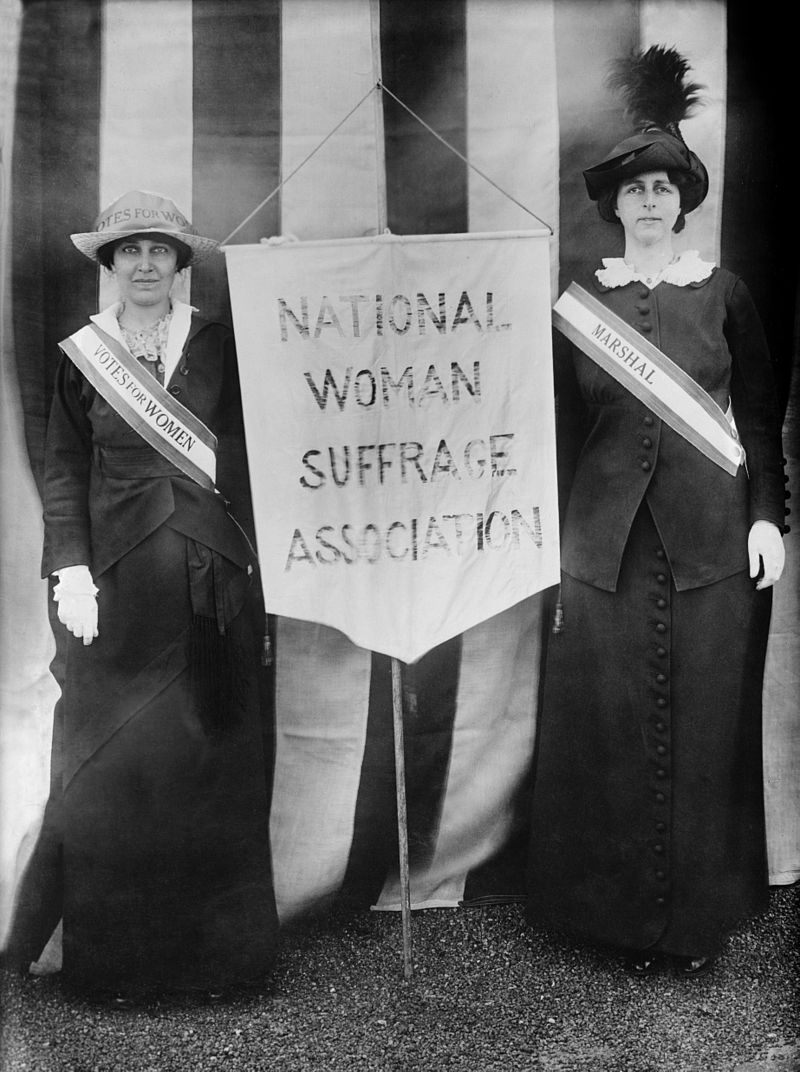

The case study to which we will effectively compare the progression of the LGBT+ movement is that of the women’s suffrage movement. One of the first public actions dedicated to women’s empowerment took place during the enlightenment era in 1509. Cornelius Agrippa authored several works as did M. Henri Baudrillard and Anthony Gibson which signified the first time that gender equality ideologies were taken seriously. Mercy Otis Warren, the sister of James Otis and a strong advocate for the American Revolution, was the first to describe the feminist struggle as an issue of ‘inherent rights.’ Mrs. Warren asserted that ‘inherent rights’ belonged to all of mankind and have been conferred on all by the God of nations.[8] The ideology of women’s inherent rights inspired scores of women to write across the west, such as Mary Wollstonecraft in London (who published Vindication of the Rights of Women in 1790) and Frances Wright in Scotland.

At the beginning of the 1800s the anti-slavery movement was gaining popularity and feminist activists found allies. The two movements often aligned their arguments as two groups of oppressed minorities fighting for their inherent rights. This alignment is evidenced by occurrences such as that of 1837 when the first National Women’s Anti-Slavery convention was held in New York, represented by seventy-one delegates. Among several results of this convention, one was the appointment of Angelina Grimke to prepare a letter for John Quincy Adams thanking him for his services in defending the right of petition for women and slaves.

Sarah Grimké was another significant figure publishing her book Letters on the Equality of the Sexes, foreshadowing many of the demands of the women’s rights movement. Her writings outlined an analogy between the condition of the woman and the slave, insisting on equality for all under the law. The anti-slavery movement provided a public forum for reformation that the women’s rights movement would later capitalize on for their own purposes.

In 1848 in Seneca Falls, New York, The Women’s Rights Convention released their Declaration of Sentiments, beginning with an amended opening of the Declaration of Independence, stating:

We hold these truths to be self-evident: That all men and women are created equal; that they are endowed by their Creator with certain inalienable rights; that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness; that to secure these rights the governments are instituted, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed…

It goes on to state:

…In view of the unjust laws above mentioned, and because women do feel themselves aggrieved, oppressed, and fraudulently deprived of their most sacred rights, we insist that they have immediate admission to all the rights and privileges which belong to them as citizens of the United States.[9]

Not long after these sentiments were expressed, Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony formed the American Equal Rights Association. This was an organization for white and black women and men who petitioned in Congress for “universal suffrage.”

Victory for the anti-slavery movement with the ratification of the 14th and 15th Amendment in 1868 and 1870 respectfully were not just victories for the anti-slavery movement. They were victories for the human rights movement and therefore belong to the anti-slavery movement, the women’s suffrage movement, and the LGBT+ movement. Each of these political and social movements had built from the same historic call for human rights regardless of race, gender, or sexuality. Such sentiments of inalienable human rights continued to grow in popularity through the ratification of the 19th amendment on August 26, 1920. This movement became a precursor for a global movement of women’s rights. In a study conducted by the Pew Research Center, the development of this movement can be seen in Figure 1.[10]

Social Holdouts

The ratification of legislation inevitably leads to social conformity. This conformity may not be universal since there are always holdouts and resistance movements. A significant instance of a social holdout for the women’s rights movement is the resilience of the glass ceiling. The glass ceiling of division between men and women is still very much intact. According to the World Economic Forum[11] as of 2021, the United States is currently ranked 30th (23 places higher than in 2020) in the global gender gap index with the UK at 23rd, France at 16th, and Iceland at 1 (See Figure 2 for full ranking). Furthermore, the world Economic Forum arrived at such rankings by sub-assessing countries on economic participation and opportunity (Figure 3), educational attainment (Figure 3) , health and survival (Figure 4), and political empowerment (Figure 4).

The culmination of such findings indicates that absolute gender equality is not perfectly achieved but that it is narrowing. The drastic and consistent improvement of the United States on this issue is evidence of the long journey toward social integration of women’s equality as established legally. However, movements toward shattering the glass ceiling cannot be allowed to fall to the wayside as newer social movements begin to transcend the gender binary.

Other lasting holdouts to the social integration of equality legislation can be observed as females’ attempts to break into senior positions in organizations and public life are often faced with male ‘homosociability.’ This takes the form of boys’ networks, male bonding, banter/sexist humor, and out of work activities that create a culture characterized by hegemonic masculinity that is commensurately hostile to women participants. Heteropatriarchal norms are socially perpetuated through media stated by Shona Bettany et al.: “there is no denying that marketing is implicated in the perpetuation of gender inequality, and the relationship between marketing, gender, and feminism remains an area of significance for marketing and consumer research in the 21st century.”[12]

Marketing practices continue to depict women (disproportionately more so than men) in domestic settings while depicting men (disproportionately more so than women) in workplace settings.[13] Such disparities continue to reinforce a gender binary by presenting an overwhelming failure to represent minority genders such as transgender, gender-neutral, non-binary, agender, pangender, genderqueer, or other individuals. Furthermore, such practices also perpetuate a heteropatriarchal norm reminiscent of a bygone time of the nuclear familial norm. As members of the LGBT+ movement increase in voicing their desires for equality, their movement has begun to harmonize with the lasting efforts of the women’s rights movement in dismantling the heteropatriarchy and attaining social and political equality through the preceding human rights movement.

The LGBT+ Rights Movement

As demonstrated by the impact of western ideologies surrounding women’s rights as demonstrated through the legalization of women’s voting and the progression of its social integration, we can conclude that the ideologies of western nations regarding gender roles hold significant potential for social and legal reform on a global scale. Therefore, we arrive at today’s situation where there is a new trend surrounding gender roles. The LGBT+ community has made significant headway since the national legalization of gay marriage on June 26, 2015, with the ruling of the Obergefell v. Hodges case.

The LGBT+ movement has aligned itself with the human rights movement since the foundation of the Society of Human Rights in 1924 as the first gay rights organization. However, due to political pressure, the organization was forced to disband only to be replaced by the Mattachine Society founded in 1950 by Harry Hay. The aim of the Mattachine Society was to “eliminate discrimination, derision, prejudice, and bigotry, to assimilate homosexuals into mainstream society, and to cultivate the notion of an ‘ethical homosexual culture.’”[14]

In an article from 1997 Paul Haglane became one of the first in the academy to conduct a study on the LGBT+ movement in conversation with the human rights movement.[15] He observed the reluctance of countries around the world to accept LGBT+ rights and acknowledge them as part of the human rights movement. He also observed the academe performing just as poorly stating:

Nor has international relations (IR) theory to date considered LGBT politics and human rights a topic of interest or scrutiny: leading theorists have simply ignored LGBT rights as a concern, whether normative or empirical. Hence the question of LGBT rights as human rights simply has not been engaged in any systematic fashion by mainstream IR theory.[16]

After Haglane’s writing, LGBT+ scholarship has increased drastically, inspiring scores of scholars such as Queer theorist Ryan Richard Thoreson who outlines two key effects of the LGBT+ movement’s engagement in the human rights conversation on an international level.[17] First, when LGBT+ activists and professionals engage in matters of legislation, social justice, or international affairs using the discourse of human rights they prompt ideas of humanity, citizenship, and responsibility that reshape the pre-existing social framework. These ideas permeate both the public and private sphere while fostering empathy at the behest of women and slaves who have fought for rights in the same way. Thoreson’s second point of significance describes a responsibility on the part of the state to protect the rights of these individuals. He states:

The violated subject may find a voice for their suffering through the international arena and may productively bring pressure on the state apparatus to rectify its wrongs, but the process ss if ultimately focused on recognition and legitimation by a state apparatus that is often quite hostile to queerness[18].

In effect, as the discourse for LGBT+ rights and social acceptance becomes more publicly recognized as a facet of the human rights movement, there is a greater responsibility on the state to protect these individuals. The perpetuating forces of the human rights movement have become a powerful aid in the political and social adaptation of the LGBT+ movement’s integration into normative practice.

Relevance of the Conversation

This conversation has become almost impossible to ignore as LGBT+ populations skyrocket in recent years. There have been increasingly more population studies conducted as individuals with non-binary gender identities are empowered to speak up and become more visible. In a study conducted by Van Caenegem in 2015 in Flanders, Belgium, findings showed that the prevalence of ‘gender ambivalence’ or non-binary individuals was 1.8% in natal men and 4.1% in natal women.[19] A recent UK study conducted in 2014 by the METRO Youth Chances organization found that 5% of lesbian, gay, bisexual, trans, and questioning (LGBT+) youth identified as neither male nor female.[20]

In a 2011 US study found that the average across all surveys conducted is 3.8 percent of adults self-identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender.[21] This implies that there are roughly nine million LGBT-identified Americans. The study went on to include an estimated nine million lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender people exist in the United States along with estimates suggesting that 8.2% of Americans (nearly nineteen million) report having had some same-sex sexual behavior since age eighteen and approximately 11 percent (nearly twenty-six million) reporting at least some same-sex sexual attraction.[22]

Equally important to the rising populations of those identifying outside of the gender binary is the social perception of such a group. In a 2011 study, it was uncovered that in American adults the perception was that 25% of the population are members of the LGBT community.[23] What we might conclude from such statistics is that not only is the LGBT community growing at an exponential rate, but public perception of the LGBT community is exceptionally higher still.

Kevin Grane is a PhD student in the University of Denver-Iliff School of Theology joint doctoral program.

[1] D. Knutson, C., Goldbach, and S. Kler. “Heteronormativity.“ In The Sage Encyclopedia of Trans Studies, edited by A.E. Goldberg and G. Beemyn (Newbury Park CA: SAGE Publications, 2021), 377-79.

[2] Brandon Robinson, “Heteronormativity and homonormativity,” The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Gender and Sexuality Studies (2016): 1-3.

[3]Christopher Chabris and Daniel J. Simons, The Invisible Gorilla: And Other Ways Our Intuitions Deceive Us (New York City: Crown, 2010).

[4] Transgender Homeless Adults & Unsheltered Homelessness: What the Data Tell Us. Washington, DC: National Alliance to End Homelessness; 2020. Available: https://endhomelessness.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/07/Trans-Homelessness-Brief-July-2020.

[5] Linn Jennings, Linn et al. “Inequalities in lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) health and health care access and utilization in Wisconsin,” Preventive Medicine Reports 14, no. 100864, (April 2019), doi: 10.1016/.

[6] L. D. Tronstad L.D. and K. Kearns, “‘Anything is helpful’: Examining Tensions and Barriers Towards a More LGBT-Inclusive Healthcare Organization in the United States,” Journal of Applied Communications Research (2021): 1–20, doi:10.1080/00909882.2021.1991582.

[7] A. Kirkland A., S. Talesh , and A.K., “Transition Coverage and Clarity in Self-Insured Corporate Health Insurance Benefit Plans”, Transgender Health 6 (2021): 207–216, doi:10.1089/trgh.2020.0067.

[8] Paul Buhle, and Mary Jo Buhle, eds. The Concise History of Woman Suffrage: Selections from History of Woman Suffrage (Champaign IL: University of Illinois Press, 2005), 51-69.

[9] Ibid.. 94.

[10] Katherine Schaeffer, “Key Facts about Women’s Suffrage around the World, a Century after U.S. Ratified 19th Amendment.” Pew Research Center, October 5, 2020[SG2] [SG3] , https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/10/05/key-facts-about-womens-suffrage-around-the-world-a-century-after-u-s-ratified-19th-amendment/.

[11] “Global Gender Gap Report 2021”, World Economic Forum, https://www.weforum.org/reports/global-gender-gap-report-2021/.

[12] Shona Bettany, Susan Dobscha, Lisa O’Malley, and Andrea Prothero. “Moving Beyond Binary Opposition: Exploring the Tapestry of Gender in Consumer Research and Marketing”, Marketing Theory 10 (2010): 3–28.

[13] A. Nassif and B. Gunter. “Gender Representation in Television Advertisements in Britain and Saudi Arabia,” Sex Roles 58(2008): 752–60.

[14] Milestones in the American Gay Rights Movement. Public Broadcasting Service, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/stonewall-milestones-american-gay-rights-movement/.

[15] Ryan Thoreson, “Sexualities in World Politics: How LGBTQ Claims Shape International Relations”, Ethics and International Affairs 30 (2016): 178.

[16] Manuela Lavinas Picq and Markus Thiel, Sexualities in World Politics: How LGBTQ Claims Shape International Relations (Routledge Taylor & Francis Group: London, 2017), 24.

[17] Ryan Thoreson, “The politics of brokerage and transnational advocacy for LGBT human rights,” PhD disseration., University of Oxford, 2011.

[18] Ibid., 17.

[19] Eva Van Caenegem, “Prevalence of Gender Nonconformity in Flanders, Belgium.” Archives of Sexual Behavior 44 (2015): 1281-7, doi:10.1007/s10508-014-0452-6.

[20] METRO Youth Chances, Youth Chances Summary of First Findings: The Experiences of LGBTQ Young People in England (London: METRO, 2014).

[21] Gary J. Gates, “LGBT Identity: A Demographer’s Perspective”, Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review 45(2012): 693.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Lymari Morales, “U.S. Adults Estimate That 25% of Americans Are Gay or Lesbian,”May 27, 2011, http://www.gallup.com/poll/147824/adults-estimate-americans-gay- lesbian.aspx.