May 1968 was known in France as l’eventement, or “the event.” It was compared to the French uprisings of 1789, 1830, 1849, and 1871 when governments dissolved and new “republics” were proclaimed. It was spontaneous, unscripted, and to a certain extent unorganized. Like so many “spontaneous” insurrections and cultural singularities of that period, there was no obvious causal chain of occurrences that precipitated it.

It was perhaps the most visible and iconic disturbance of that now iconic period in Western history, which current historical consensus now seems to agree ushered in the transition from the modern to the postmodern. It was the last of the great revolutionary spectacles that were to convulse the Western world. But what does it mean today, if anything at all?

The year 1968 has already gone down in the annals of Western historians as the last great transcontinental “revolutionary” earthquake comparable perhaps to 1848 and 1917. The success of the Vietcong and North Vietnam armies in the Tet Offensive that spring forced the resignation of US President Lyndon Johnson. Simultaneously, the assassinations of presidential candidate Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King fomented an unprecedented crisis atmosphere in American politics, which was matched by the challenge to the hegemony of the Soviet Union in Eastern Europe by the so-called “Prague Spring” which ended with an invasion of Russian tanks.

But it was the headline-grabbing incidents in Paris that took center stage. Students walked out of classes at universities all over the country. Workers staged what came closest to Georges Sorel mythical “general strike” than had happened at any time in modern French history. France’s President and World War II resistance hero Charles DeGaulles fled the Élysée Palace in order to prevent a confrontation between the insurrectionists and the national army.

At the same time, the events of May 1968 have also been called by Michael Seidman the “imaginary revolution,” largely because the drama was over almost soon as it flared up, and nothing really changed politically once it was all over. By June the Gaullist regime was more entrenched than ever.

Whether it was “imaginary” or not with respect its tangible, political outcomes, May 1968 came to be seared in the memories of activists and intellectuals alike, who as loose aggregate of political thinkers were then and later known as the New Left. It was at the same time decidedly a cultural revolution, inasmuch as it flaunted a critique of virtually every established social practice and institutions.

Finally, it was inherently anti-collectivist, as all revolutions had been. The famous slogan of both the student movement in America and second-wave feminists that the “personal is political” was derived in many respects from the same sentiment that inspired the Paris radicals.

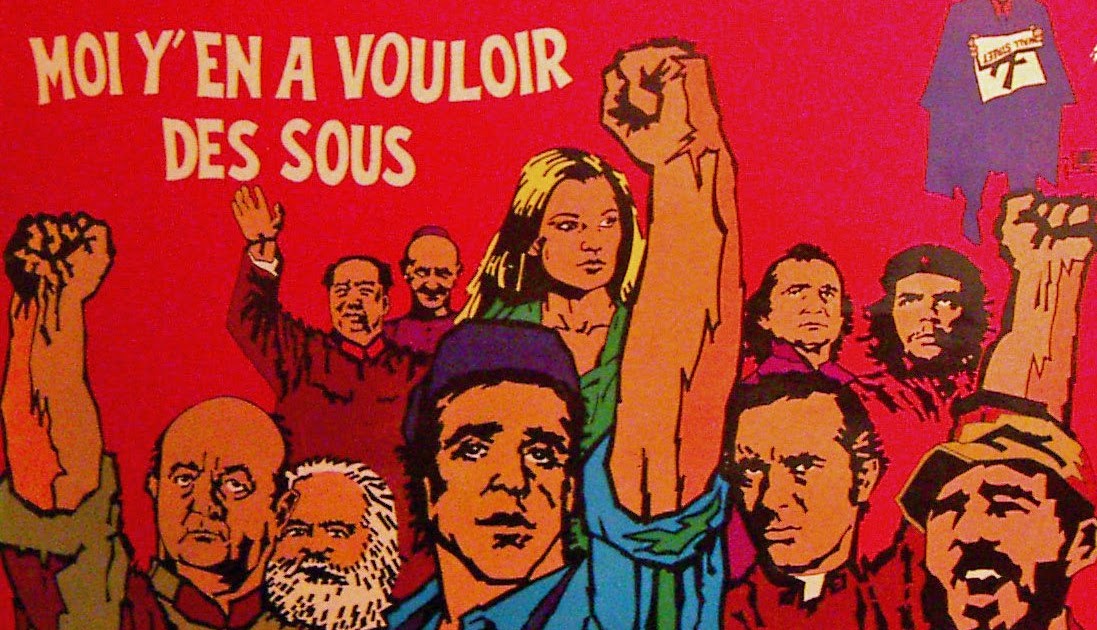

A telling example is the common placard slogan seen repeatedly during the chaos of that memorable month. The famous Jacobin motto liberté! egalité! fraternité! was re-inscribed as liberté! egalité! sexualité!. There could be no political revolution without a sexual revolution, which in turn morphed into an insurrection of previously unacknowledged or marginalized social groups deploying the established rhetoric of Marxist firebrands to a signally different purpose.

“Class consciousness” now came to be differentiated and dissociated in terms of the now standard “intersectional” categories of race, gender, sexual identity, and ethnicity. From l’eventement there emerged gradually, but relentlessly a reorientation of radical politics away from the kind of millenarian historicism and universalism that had suffused Marxism, socialism, and even Christian progressivism throughout the first half of the twentieth century along with a new fixation on structures of oppression that could no longer be codified through economic discourse.

What Jean-François Lyotard had termed a “distrust of metanarratives” became the new norm, manifesting in a hypercritique of all secular soteriologies from liberalism to historical materialism that arose from a broad spectrum of intellectual sources. The fact that the enragés of May 1968 centered their polemical attacks on both orthodox Marxism and the favored emancipatory narratives of French bourgeois nationalism going all the way back to Napoleon was a testimony to this special legacy.

Thus the true bequest of May 1968 was an intellectual one, and it had perhaps the greatest impact on America since Lafayette and the French armies blocked the British resupply fleets from the harbor at Yorktown in 1781, thereby ensuring the victory of the rebel colonists in the War of Independence.

From 1969 onward the writings of French post-structuralists and “neo-Marxists” who had both participated in, and been theoretically molded by, l’espirit of the previous year, began to fill the new intellectual canon of post-Vietnam American academia. From Michel Foucault to Jacques Derrida, from Julia Kristeva to Luce Irigaray, what eventually came to be known as “postmodern” philosophy became the dominant genre of avant-garde letters.

Indeed, at the political level one of the most influential movements that planted the seeds of what came to be known as “identity politics” were the writings of the New Historicists, pioneered by Catherine Gallagher and Stephen Greenblatt, which they characterize as “a fascination with the particular…the refusal of universal aesthetic norms, and the resistance to formulating an overarching theoretical program.”(6) Gallagher and Greenblatt took many of their cues from the writings of Foucault, especially his general notion which at the end of his career he termed “technologies of the self.”

Foucault explains the meaning of the concept of “technologies of the self” in a seminar he gave at the University of Vermont in 1982:

My objective for more than twenty-five years has been to sketch out a history of the different ways in our culture that humans develop knowledge about themselves: economics, biology, psychiatry, medicine, and penology. The main point is not to accept this knowledge at face value but to analyze these so-called sciences as very specific “truth games” related to specific techniques that human beings use to understand themselves. (224)

Foucault’s general idea that theorizing – even political theorizing – must somehow always be grounded in the practice of self-formation through an expansion of the process of reflection from one’s own experience, especially as a result of personal subjugation and the techniques of resistance to it, thus evolved into an overhanging conceptual template for analyzing systems of social marginalization and domination.

Simultaneously, the dialectical paradigm of class conflict and revolutionary struggle diffused into a preoccupation with singular and more nuanced forms of oppression which clamored for equal status with generic forms of injustice. Whereas Marxism in particular with its claim of the proletariat as the “universal class” had performed a unique kind of synecdoche with the part signifying the whole, the new genre of political rationality repudiated, in effect, such a way of thinking as both privileging and patronizing.

The dialectic was torn asunder and replaced with a kind of agonism of disrespected subjectivities all competitively vying for cognizance and a route of escape from a history of enforced invisibility. The politics of “identification” was, according to Nancy Fraser, in reality a “politics of recognition,” a term that traces back to Hegel’s “master slave dialectic” in the Phenomenology of Spirit.

Whereas the early politics of recognition has historically been truly liberationist, according to Fraser, particularly when it was paired with demands for the redistribution of social and economic benefits to excluded communities, its latter day expression as “identity politics” has reduced its former emancipatory potential to a legitimation of group-think. In her article “Rethinking Recognition” written in 2000, Fraser criticizes identity politics as having “the overall effect…[of imposing] a single, drastically simplified group identity which denies the complexity of people’s lives, the multiplicity of their identification and the cross-pulls of their various affiliations.”

In a variety of subsequent books and essays Fraser documents the transformation of identity politics into a subtle ideology of neoliberal economic hegemony, which manipulates the “vulgar culturalism” behind such a “reified” taxonomy of group differences into a permanent conflictual logic that entrenches the power of progressive or “cosmopolitan” elites around the world.

Looking back, therefore, we may conclude that the uprisings of May 1968 truly shattered once and for all the modernist “humanistic” metanarratives of secular salvation through the historical development of the species. The mantra of politics as personal became for a short while at least the catalytic converter for a new vision of effective grass-roots solidarities that served to eliminate the secret and unspoken mechanisms of oppression which earlier generations of revolutionaries had overlooked.

But in the same breath l’eventement also unleashed new strong forces of atomization, reification, and commodification which, superimposed upon the global triumph of consumer capitalism after the collapse of international communism, paved the way for the kind of neoliberal hegemony that has entrenched the power of the global ruling classes who go by the nickname of the “one percent.”

The old saying that “revolutions devour their children” is not an adage that pertain only to past social upheavals and political turnabouts on the dais of world history. The “children” who are now known as “millennials” have not been so much “devoured” as dispossessed.

The “imaginary revolution” of 1968 must be re-envisioned at this point as a real social and political insurgency that does not repeat history, but re-engages with it profoundly and resolutely.

Carl Raschke is Professor of Religious Studies at the University of Denver, specializing in Continental philosophy, art theory, the philosophy of religion and the theory of religion. He is an internationally known writer and academic, who has authored numerous books and hundreds of articles on topics ranging from postmodernism to popular religion and culture to technology and society. Recent books include Postmodern Theology: A Biopic (Cascade Books, 2017), Critical Theology: An Agenda for an Age of Global Crisis (IVP Academic, 2016), Force of God: Political Theology and the Crisis of Liberal Democracy (Columbia University Press, 2015) and The Revolution in Religious Theory: Toward a Semiotics of the Event (University of Virginia Press, 2012).