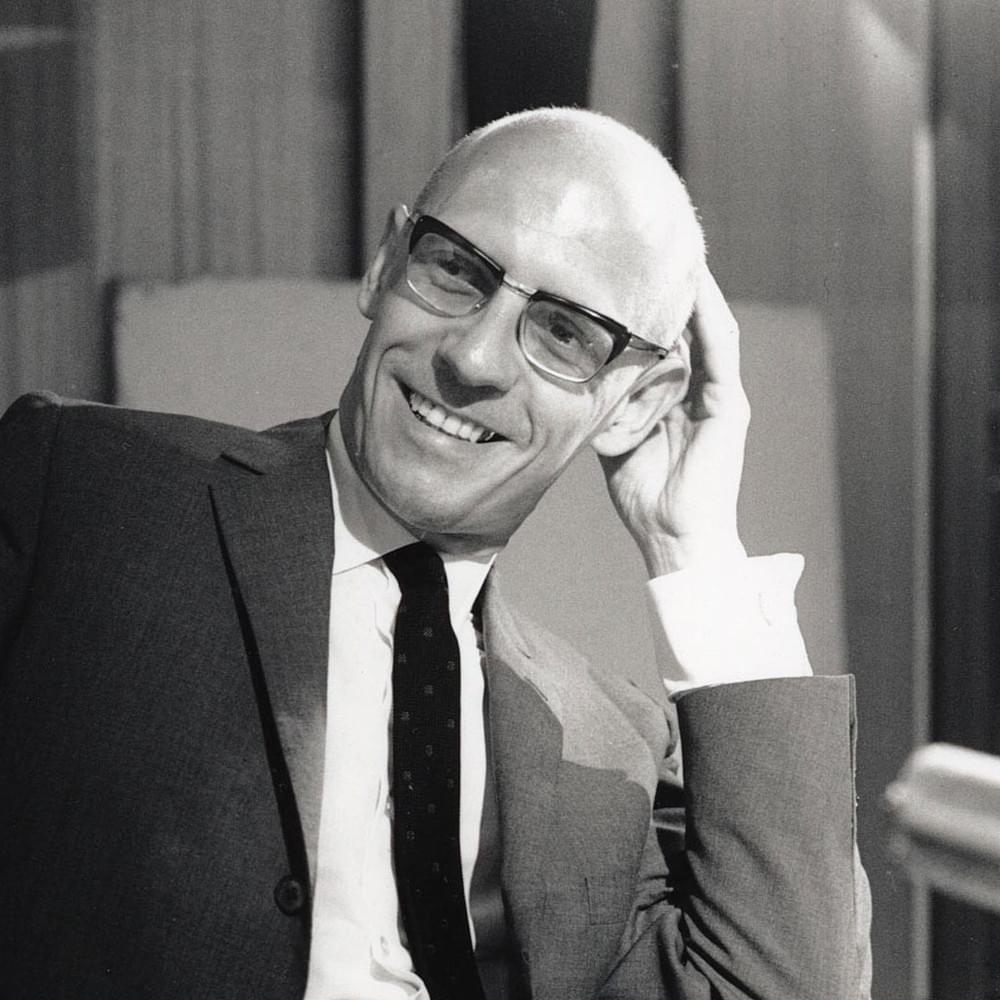

Recently scholars have begun to consider various ways that the work of Michel Foucault and James Baldwin might converge. Typically, comparisons between the two writers have been staged on the field of politics, through considerations of how they thought, for example, about power or identity.(47-64) Instead this paper proposes to consider Foucault and Baldwin as reluctant prophets, that is, as thinkers who reject one mode of prophesy but that they finally end up espousing another modified, chastened form of prophetic thought. I argue that both men are suspicious of the universal intellectual who seeks, in Foucault’s terms, to serve as legislator and prophet.

In other words, the modern conception of the intellectual is one that both should and must be rejected. It should be rejected, among other reasons, because the Enlightenment model of the universal intellectual forgoes risk in favor of objectivity. Another problem that Foucault pinpoints in his characterization of the prophet is the problem of representation, that by which an intellectual speaks on behalf of another. Both the problem of objectivity and the problem of representation are problems that Foucault traces back to the conception of the intellectual as prophet. Nevertheless, I argue that Foucault and Baldwin provide us with a conception of intellectual prophecy that avoids these pitfalls.

The question concerning the intellectual’s role in modern society is a recurring theme throughout Foucault’s writings, though this theme manifests itself more in his occasional writings and lecture courses than in his published writings. For example, “Intellectuals and Power,” a dialogue between Foucault and Gilles Deleuze conducted in March of 1972, addresses the changing role of the intellectual in modern European societies.

This piece dates from the pair’s involvement with the Groupe d’information sur les prisons (GIP), a loosely-affiliated group of intellectuals and activists who sought to provide French inmates with a platform so that they could draw attention to the squalid prison conditions in France. It was important to the intellectuals involved that the prisoners be given an opportunity to speak for themselves rather than acting as their representatives. Hence, one of the topics covered in the dialogue was representation, i.e. an analysis of the various conditions under which the intellectual should be authorized to speak on behalf of another.

By 1972 Foucault has already begun to contest the Marxist conception of the engaged intellectual, according to which the intellectual both speaks on behalf of the exploited proletariat and attempts to get the members of this class to see their own wretchedness. By 1972 Foucault sees that this conception of the engaged intellectual, one that extends from Marx and Engels at least through Sartre, was inadequate. He endeavors to replace this Marxist conception of the engaged intellectual who speaks on behalf of others and serves as their representative with the conception of the specific intellectual. Among other things, this individual does not pretend to have privileged knowledge that remains inaccessible to those she represents.

Baldwin poses this question of representation in various ways throughout his work as well, but the need to think through its implications becomes especially acute during the 1960s as he becomes more involved in the Civil Rights Movement. The Fire Next Time, which became a manifesto of the movement, consists of two essays: a shorter one entitled “My Dungeon Shook” written as a letter addressed to his nephew James, in which he implores him not to internalize the racist ideals of the dominant white culture.

The second, longer essay “Down at the Cross” presents, among other things, an extended reflection on how the Christianity of his youth and the Islam of Elijah Muhammed both repeat the sins of the dominant white culture and thereby fail their prophetic vocation. And here we see Foucault and Baldwin diverge: Foucault’s critique focuses primarily on the secular Enlightenment figure of the prophetic intellectual that Marxism inherits, while Baldwin’s critique of prophecy focuses on his own vexed relationship with the black church.

Despite these differences in focus, we also find in Baldwin’s work a sustained critique of the (white) intellectual’s pretensions to objectivity. Baldwin sees these pretensions as a function of white innocence, a form of epistemic blindness that he claims is characteristic of white identity that manifests a retreat from reality that blinds white people to the tragic dimension of existence. African-Americans generally lack the luxury of this blind innocence.

My essay proceeds in two parts: I begin with Foucault’s analysis of modes of truth in his final lecture course, The Courage of Truth. Prophecy is understood as a form of truth-telling that differs in important ways from philosophical parrhesia. I conclude this section by considering Foucault’s analysis of the Cynical attitude. This rehearsal of The Courage of Truth provides the basis for my reading of Baldwin’s early writings in second section, in which I read him in terms of prophetic Cynicism.

Prophets, Philosophers, Truth-Tellers, and Cynics: The Courage of Truth

In his final Collège de France course Foucault focuses is on the nature of parrhesia, and it continues the investigation of fearless speech begun during the previous year’s course. He begins, as he so often does in the lecture courses, with an attempt to define the term. Parrhesia is an attitude in which the truth-teller risks herself by telling the truth. It’s not a technique, but rather a specific modality of truth-telling. Foucault proceeds to contrast parrhesia with three other modes of ancient truth-telling: prophecy, wisdom, and teaching.

Three ways of being correspond to these modes of truth-telling, those of the prophet, the sage, and the teacher. The prophet speaks in another’s name, usually that of a divine figure. Foucault writes that, while the prophet tells the truth just as the parrhesiast does, “the prophet, by definition, does not speak in his own name. He speaks for another voice; his mouth serves as the intermediary for a voice which speaks from elsewhere.

The prophet, usually, transmits the word of God.”(15) Like the figure of the poet in Plato’s Ion, the prophet mediates between the divine and the human, and is therefore divinely inspired. While both the parrhesiast and the prophet function as truth-tellers, they are opposed in each of these specific respects. While the parrhesiast speaks in her own name, the prophet is a divine mouthpiece. Indeed, Foucault calls this speaking-for-oneself “the price of [the parrhesiast’s] frankness.”(16)

While the prophet’s words are meant to foretell future events, the parrhesiast’s words focus squarely on the present. “He unveils what is,” Foucault writes. Finally, whereas the parrhesiast’s focus lies in the current conditions and speaking out against these, the prophet’s words pertain to something otherworldly—either a future to come or an otherworldly realm that transcends this one.

The parrhesiast’s focus is mundane, while the prophet’s is extramundane. In this way, the parrhesiast’s task here can be characterized as a moral one: “[The parrhesiast] helps them in their blindness, but their blindness about what they are, about themselves, and so not the blindness due to some moral fault, distraction, or lack of discipline, the consequence of inattention, laxity, or weakness.”(16) Their social functions are both revelatory, but in very different ways.

The prophet speaks in riddles that burden her audience with the task of interpretation, while the parrhesiast speaks plainly and thereby burdens her audience with a moral task that demands a fundamental change in how they’ve been living their lives. Although he never references “Intellectuals and Power” in The Courage of Truth, the ancient prophet, like the modern Marxist intellectual, represents another, though she interprets the divine word for a human audience.

Recall that Foucault in 1972 had criticized the prophetic Marxist intellectual who speaks on behalf of the exploited masses and promises a future world where they will be free of exploitation. Foucault’s relative interest in the prophet can be inferred from the fact that he course focuses on the parrhesiast, the individual who speaks directly and frankly, rather than the individual who serves as the gnomic mouthpiece of the gods. The prophet is introduced as a contrast to the parrhesiast, the frank teller of direct truths.

But the main difference between the prophet and the sage is that the sage “speaks in his own name.”(16) The sage must manifest herself in the words she speaks, but she feels no special need to speak. Indeed, this reticence is the feature that most readily distinguishes the sage from the parrhesiast. The sage’s words, like those of the prophet, can be enigmatic and make an interpretive demand upon their audience; nevertheless, the sage’s utterances yield prescriptive value in the form of “a general principle of conduct.” The parrhesiast, by contrast, has a duty to speak absent in the sage’s relationship to truth. Finally, Foucault briefly contrasts the teacher as the technician of truth with the parrhesiast.

Foucault distinguishes these three modes of truth-telling from parrhesia early in the course so that he can complicate them later on. Socrates embodies the first complication of the neat distinction between the four modes of truth Foucault presents in the first hour of The Courage of Truth. Indeed, he claims that one of the reasons to return to the Greeks is because one can find these modes of truth-telling neatly distinguished, though not for long.

“Already you can see how Socrates puts together elements of prophecy, wisdom, teaching, and parrhesia. Socrates is the parrhesiast.”(26) But, Foucault quickly reminds us, it was the oracle at Delphi (that is, truth-telling in a prophetic mode) that makes Socratic parrhesia possible, so we cannot neatly distinguish between Socrates the prophet and Socrates the parrhesiast.

In a similar fashion, Socrates is also a figure of wisdom, which transmutes the sage’s reticence into Socratic ignorance. Finally, at times Socrates also embodies the technical acumen of the teacher, albeit reluctantly and ironically. These four groupings form the basis of an organizing structure that Foucault will employ in these final lectures to show how philosophy works both in ancient Greece and in more recent epochs.

Roughly, Foucault claims here that Greco-Roman philosophy “brought together the modalities of parrhesia and wisdom” while the Middle Ages fused the prophet with the parrhesiast on the one hand and wisdom with teaching in the context of the university on the other. Foucault’s analyses of the various ways these four modalities of truth are combined and recombined in various historical contexts extend all the way to the modern era once he begins thinking about the figure of the Cynic, to which I now briefly turn. I will conclude this section with a brief examination of this figure in The Courage of Truth before thinking about how Baldwin might fit into Foucault’s genealogy of the modes of truth-telling in the second section of my paper.

The second hour’s lecture on the 29 February represents a departure in the course. Foucault has just completed his analysis of Socrates’ ethical parrhesia and he is turning his attention to the ethical parrhesia of the Cynics. He points out that the initial interpretive problem is that it is impossible to discern a distinctive Cynical doctrine.

Hence it is better to consider the Cynical tradition as “an attitude and way of being, with, of course, its own justificatory discourse.”(178) Consequently, it recurs in various guises throughout the centuries, what Foucault calls “a trans-historical category.” He is struck by how German authors are returning to the Cynics, citing Paul Tillich, Klaus Heinrich, Arnold Gehlen, and Peter Sloterdijk (though he focuses on the first three because he has yet to read the Sloterdijk).(178-79)

Tillich, Gehlen, and Heinrich all distinguish between ancient and modern forms of Cynicism, between Kynismus and Zynismus, and they all focus on the individual’s assertion of her own existence in opposition to the uncertainties of the ancient world and the absurdity of the modern one, but this focus on individualism misses the core problem at the heart of Cynicism which is that “of establishing a relationship between forms of existence and manifestation of the truth.”(180)

Foucault emphasizes three permutations of the Cynic mode of being in Europe. The first is the institution of asceticism in early Christianity and the role that these practices of bearing witness to the scandal of truth play in the medieval Church. He next sketches a modern example “of Cynicism understood as form of life in the scandal of the truth,” exemplified by the figure of the political revolutionary, understood as both a form of life and a form of sociality.(183)

Finally, he sketches this Cynical attitude as it expresses itself in modern art. Art’s scandalousness no doubt has a long history, but Foucault finds the Cynical attitude especially relevant in modern art in two basic ways. First, artists’ lives become a fascination for people, and the style of each artist’s life should be a testament to the truth of her art: “The artist’s life must not only be sufficiently singular for him to be able to create his work, but it must in some way be a manifestation of art itself in its truth.”(187) And, secondly, modern art strips existence bare, down to its essentials. “Art (Baudelaire, Flaubert, Manet) is constituted as the site of the irruption of what is underneath, below, of what in a culture has no right, or at least no possibility of expression.”(188)

Modern art is the Cynic’s refusal to abide by established cultural norms. “The consensus of culture has to be opposed by the courage of art in its barbaric truth. Modern art is Cynicism in culture; the cynicism of culture turned against itself.”(189) Asceticism, revolt, art: three modes of Cynical life that develop out of the original provocations of the ancient Cynic.

In this first section, I’ve spent some time thinking about a couple key moments from this last lecture course because we find Foucault thinking about how truth relates to life, and some of the various forms that this true life might take. It is clear that Foucault is interested in the question of the relationship between truth and existence up until the end of his life. He remains suspicious of various prophetic modes of truth-telling, but nevertheless he sees that these are important for understanding the adversarial role of philosophy in ancient and modern culture.

But I also want to show how Foucault and Baldwin are both suspicious of the prophet understood as a figure who either represents the downtrodden and speaks on their behalf or represents a divine Other and speaks in her name. So, Foucault and Baldwin both critique this conception of prophecy, but (and this is the reason for my examination of The Courage of Truth) I believe that Foucault’s analysis of the Cynical attitude can help us make better sense of Baldwin’s distinctive prophetic voice.

Baldwin as Cynical Prophet

For Baldwin whiteness means the privilege of innocence. He pronounces this white innocence in many places throughout his work. Most famously, perhaps, is the pronouncement of white innocence in The Fire Next Time. However, white innocence is a brutal form of forgetting. As he writes to his nephew in “My Dungeon Shook,” “This innocent country set you down in a ghetto in which, in fact, it intended that you should perish. […] You were born into a society which spelled out with brutal clarity, and in as many ways as possible, that you were a worthless human being.”(293)

He had previously noted that this innocence in fact constitutes the crime. Only the innocent can flee from reality, but this innocence of whiteness comes at a steep cost. Toward the conclusion of The Fire Next Time, Baldwin lays out its terms:

Behind what we think of as the Russian menace lies what we do not wish to face, and what white Americans do not face when they regard a Negro: reality—the fact that life is tragic. Life is tragic simply because the earth turns and the sun inexorably rises and sets, and one day, for each of us, the sun will go down for the last, last time. Perhaps the whole root of our trouble, the human trouble, is that we will sacrifice all the beauty of our lives, will imprison ourselves in totems, taboos, crosses, blood sacrifices, steeples, mosques, races, armies, flags, nations, in order to deny the fact of death, which is the only fact we have. […] But white Americans do not believe in death, and this is why the darkness of my skin so intimidates them.(339)

This passage is significant for two reasons. First, it shows Baldwin’s complicated relationship with religious faith, a theme that runs throughout The Fire Next Time and Baldwin’s work more generally. Political theorist George Shulman argues in his book American Prophecy: Race and Redemption in American Political Culture that Baldwin sought to secularize the prophetic vision of his dear friend Martin Luther King, Jr.

Whereas King used the language of prophecy to show how African-Americans could only be redeemed through the holy and moral struggle against racism. But this struggle is not holy for Baldwin, nor is the suffering endured by African-Americans redemptive. Nevertheless, it does provide a painful insight that is lost on white Americans who have the luxury of flight.

Secondly, the above passage shows how Baldwin replaces King’s theistic moral prophecy with a Cynic’s moral prophecy. Innocence is a form of blindness that makes it impossible to see reality for what it is: contingent and ever-changing. Baldwin the Cynic announces that the acknowledgement of the tragic reality revealed by the precarious lives lived by most African-Americans is the very condition of freedom.

“But the renewal becomes impossible if one supposes things to constant that are not—safety, for example, or money, or power. One clings then to chimeras, by which one can only be betrayed, and the entire hope—the entire possibility—of freedom disappears. And by destruction I mean the abdication by Americans of any effort really to be free.”(339) Freedom can only be found in the acknowledgement of finitude.

And, just as Foucault finds the Cynical attitude displayed in modern art and the figure of the modern artist, Baldwin sees the important role that art plays in this secular prophet’s call to remember the horrors of history that condition the American present. In a short essay written in 1962 (roughly contemporaneous with The Fire Next Time) called “The Creative Process,” Baldwin discusses what Foucault would later call the artist’s cynical attitude.

He begins with the claim that the artist’s task is to cultivate the state of being alone. Here Baldwin begins with the figure of the artist and the distinctive task that the artist faces—to cultivate loneliness. The artist’s sole task is to simply make sense of himself, but for Baldwin this making sense of oneself must occur in extremis. “The state of being alone is not meant to bring to mind merely a rustic musing beside some silver lake. The aloneness of which I speak is much more like the aloneness of birth or death. It is like the fearful aloneness which one sees in the eyes of someone who is suffering, whom we cannot help.

Or it is like the aloneness of love, that force and mystery which so many have extolled and so many have cursed, but which no one has ever understood or really been able to control […]The states of birth, suffering, love, and death, are extreme states: extreme, universal, and inescapable. We all know this, but we would rather not know it. The artist is present to correct the delusions to which we fall prey in order to avoid this knowledge.” By cultivating the Cynic’s loneliness, the artist might dispel, among other things, the delusional innocence of whiteness. It is this power which makes the artist “an incorrigible disturber of the peace.”(669)

Baldwin’s prophetic task is to call us back from the serenity of history told as a fairytale that denies the brutal conditions under which this nation was founded. In doing so, he combines the modes of prophecy and Cynical parrhesia to herald a future that he hopes will be radically different from our present. It is only through acknowledging this past and working through it that we can become worthy of ourselves—a Cynic’s task if ever there was one.

As he writes in “Nothing Personal” in 1964: “It is perfectly possible—indeed it is far from uncommon—to go to bed one night, or wake up one morning, or simply walk through a door one has known all one’s life, and discover, between inhaling and exhaling, that the self one has sewn together with such effort is all dirty rags, is unusable, is gone: and out of what raw material will one build a self again? The lives of men—and, therefore, of nations—to an extent literally unimaginable, depend on how vividly this question lives in the mind.”(695)

Corey McCall is Associate Professor of Philosophy at Elmira College in upstate New York. His research interests include aesthetics and political philosophy. He is co-editor of Melville Among the Philosophers (Lexington Books, 2017) and Benjamin, Adorno, and the Experience of Literature, forthcoming from Routledge later this year.