The New Polis is honored to present Dr. Tinker’s follow-up piece to “Redskin, Tanned Hide: A Book of Christian History Bound in the Flayed Skin of an American Indian: The Colonial Romance, christian Denial and the Cleansing of a christian School of Theology,” published in The Journal of Race, Ethnicity, and Religion, Volume 5, Issue 9 (October 2014). Due to the importance of source work for this piece, we have left all of Dr. Tinker’s own notes and citations intact at the and of the draft. We have only added hyperlinks when helpful and broken paragraphs for online readability.

“Damn it, he’s an Injun!”

The settlers on the upper waters of the Monongahela often went in canoes and flat-boats to Fort Pitt, where they exchanged skins, furs, jerked venison, and other products of the wilderness for ammunition and necessaries. Jesse Hughes and Henry McWhorter made a trip together. One day they put ashore where a number of children were playing, among them a little Indian boy. The incident which followed I will give in McWhorter’s own words. [i.e., Henry McWhorter, the author’s great grandfather]

“The instant that Jesse caught sight of the little Indian boy his face blazed with hatred. I saw the devil flash in his eye, as feigning great good humor, he called out, ‘Children, don’t you want to take a boat ride?’ Pleased with a prospective glide over the still waters of the Monongahela, one and all came running towards the boat. Perceiving Hughes’ cunning ruse to get the little Indian into his clutches, I picked up an oar, and gruffly ordering the children away, quickly shoved the boat from the bank. When safely away, I turned to Hughes and said, ‘Now, Jesse, ain’t you ashamed?’ ‘What have I done?’ he sullenly asked. ‘What have you done? Why, you intended to kill that little Indian boy. I saw it in your every move and look, the moment you got sight of the little fellow.’ ‘Yes,’ he said, ‘I intended when we got into mid-stream to stick my knife in him and throw him overboard.’ When I remonstrated with him about this, he said, ‘Damn it, he’s an Injun!'”

For Jesse Hughes the day of actual conflict had passed. The red warrior no longer haunted the Virginia wilderness, but desultory bands of friendly Indians, degraded by the vices of the white man’s civilization (5) still lingered round their former homes and the graves of their people. These spent much of their time in wandering about through the white settlements and often indulged in drunken carousals. Against these beings, Jesse continued to glut his insatiate thirst for Indian blood….

Jesse’s awful vow of his younger days, “to kill Injuns as long as he lived and could see to kill them,” was fearfully and savagely kept in the eventide of his life. The laws for the protection of life were ineffective on the border and were seldom enforced when the victim was a “despised redskin.”

– McWhorter[2]

About April 1, 1779, David Morgan (1721-1813), a euro-christian colonialist, murdered two Lenape Indian men on a piece of western virginia frontier land on which he had made a property claim and had started farming. His farm was close by, about a mile, the small fort the new invasive euro-christian community had built. Already by the mid-1750s, during the north american portion of the Seven Years War of England with France (in U.S. histories the north American portion is commonly called the “French and Indian War”[3]), a series of forts were constructed along what is now the eastern boundary of west Virginia on a line due south of the Fairfax Line —a couple of hundred miles east of what was to become David Morgan’s property claim a quarter century later.[4]

While many of these were military garrisons built under orders of the Virginia governor, the majority were settler constructed forts, built by each local invader-settler enclave and designed to protect settler enclaves against Indian resistance to invader presence in Native territory.

The part of that european war played out in north America was one to determine whose Right of (christian) Discovery was to prevail over the lucrative Native lands of the Ohio River valley. So these forts (both civilian and military) marked the advancing anglo-christian frontier—each falling into disuse as the frontier passed them by and as english christian folk penetrated ever deeper into Native territory. By the mid-1770s Morgan had himself participated in building one of these front-line forts along the Monongahela River, one of the upper watersheds to the Ohio.

David Morgan: Indian Killer

I killed seven Indians in my life.—David Morgan, in his family Bible[5]

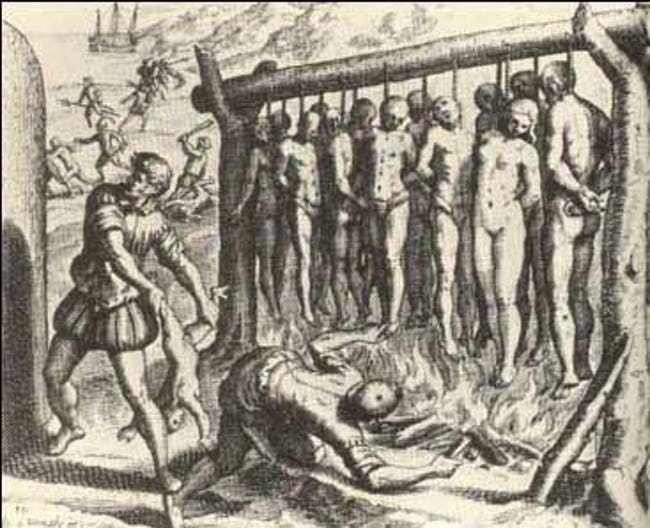

After Morgan’s murder of these two Lenape men, in an act considered ghastly and grotesque by Indian People to this day, fellow colonialists flayed the skin of the victims and used their tanned hides for making souvenir curios, including, we are told, the cover for a book of christian history. That book became a treasured holding at a christian graduate school of theology a century after the murders, a prized gift from a local methodist minister.

In a previous essay I documented that school’s history of shame with regard to the covering of that book and their secretive disposal of the cover in 1974 after 80 years of keeping it on public display.[6] This essay attempts to describe the larger context of horror that would generate such an atrocity.

David Morgan, a scion of a notable welsh quaker immigrant family, had been among the first euro-christian settlers on the upper Monongahela in 1774. He had undoubtedly walked the land more than two decades prior as a surveyor with a crew working on behalf of Lawrence Washington and the Ohio Company scouting out lucrative speculative lands on the company’s behalf. In the process Morgan would have become privy himself to prime choices in Native land—as surveyors generally did.

A friend and neighbor to Jacob Prickett, Morgan would have helped in constructing Prickett’s Fort, the civilian fortified refuge for these invasive settlers built in 1774. Morgan, Prickett, and the others in that initially small enclave of euro-christians were actually squatters on Indian land, a common euro-christian practice that persisted into the 20thcentury. Their “property” claims were effected by occupation at that date; only in 1776 was their property “ownership” ratified by the new national congress in Philadelphia.

Of course, Indian people of that region were not a part of the congress’ deliberations in 1776 and would have only begun to hear word of mouth about this new government by 1779. And, of course, notions of property, individual rights of ownership, or private property would have entirely foreign to the Natives who lived and hunted on that land.[7]

What was David Morgan’s claim to this land, and what were the circumstances of these killings? Who were these two Indian men and what were they doing? What else is going on in David Morgan’s world as he draws aim with his rifle on the first Indian he kills? The answers are incredibly complex and multifaceted, buried beneath deep layers of colonialist romance and self-serving colonialist histories.

Getting at some of this history is difficult, requiring a thorough excavation of the exotic colonialist narrative. Yet we have some basic knowledge with which to begin. We know that a man died and was skinned, simply because of the documented history of the book held in the library of Iliff School of Theology that was covered with the tanned skin of one of these victims. Indeed, it becomes quickly apparent that there were two victims killed that day. We know when the incident happened, 1779, and we know where it occurred, near Rivesville in modern W. Virginia. And we know that David Morgan was the perpetrator—at least of the murders.

This essay is an attempt to explicate further why this could occur and how it may have played out. As a narrative, my interpretive history here breaks decidedly with the christian colonialist telling of history, and there is no doubt that it will leave some readers unhappy and unconvinced.[8]But it deserves to get a hearing, and I will argue that it is has a high degree of probability as historical explanation.

I suspect that David Morgan killed one Indian man in cold blood. Ambush. That would have been easy enough. But then he discovered a second man and found himself in a second, unexpected fight. Having fired his rifle at his first victim, he no longer had a loaded weapon, so he was forced to engage in a hand-to-hand fight. This narrative, however, cannot be satisfied merely with the solving of a crime. Rather, it must look at the whole social context of these murders in euro-christian colonial north America and pay attention to the dominant social imaginary shared across euro-christian north America about Indian Peoples.

The prime question—since the beginning of the euro-christian invasion—has to do with how the colonial settler population is always able to rationalize their christian faith and upbringing given the violence they systematically perpetrated against the people who already lived on this continent. In this case they proudly flouted their violence in one of their most sacred religious venues—namely, the methodist school of theology where I taught for 32 years.

It was not the case that we Indian folk were not yet considered human. Euro-christian people had decided that point for themselves in the 1550-51 Valladolid debate between two academically inclined spanish catholic bishops, intellectuals of the late renaissance. And from the beginning, euro-christian invaders were unquestionably able to communicate with Native Peoples as fellow human beings. The separatist pilgrims at Plymouth had Tisquantum, who had been kidnapped and had lived some time in England, learning the language; Hernán Cortés had Doña Marina, whose intellect allowed her to quickly learn Cortés’ language.

Indeed, we are told that Morgan spoke bits and pieces of three Indian languages, including the language of the two victims he murdered. So euro-christian folk knew full well that Indian Peoples were, like themselves, rational human beings quite capable of precise communication, even as they devised a narrative to accord Indians less-than (savage) status.

At some level they fully knew they were in violation of their own code of “commandments,” as in “thou shalt not steal,” “thou shalt not covet anything that is thy neighbor’s,” and “thou shalt not kill.” In the case of Morgan and the upper Monongahela Valley, the same basic knowledge had to be true as well. Namely, Morgan, William Crawford, George Washington, much like Governor John Evans and the Rev. John Chivington nearly a century later, all knew full well that they were pushing Natives off of the land in order to take Native lands to make room for euro-christian invasive settlement.

The murder and displacement of Native Peoples did not just happen, however. There was, at some level, a self-conscious plan and execution—even if the result was a lingering habitual behavior in the greater euro-christian public. As christian folk, though, the invaders needed to create some fiction about their invasion that could / would justify and excuse their violence, particularly their violence over against the Native inhabitants of the land they so coveted. Even as David Morgan was a consumer of the narrative, the story that spread recounting his murder of two Indians immediately became part of that much larger constructed narrative of christian excuse and denial.

Versions of the David Morgan Indian-killing legend proliferated very quickly after the event. Most of these stories were highly romanticized versions, particularly adding details precisely to exonerate and heroize the protagonist. By early 1779 Morgan would have been 57, no longer a young man, so the tale of his hand-to-hand combat with a younger, stronger Indian man adds to the heroic narrative. All these variant accounts reach out and grab a euro-christian authence in such a way that the violence in no way requires exoneration but rather just the opposite, generates christian exhilaration and celebration.

Indeed, the romance continues to express sympathy for heroes like Morgan and continues to cast Indians as permanent enemies, savages, and casts the White christian settler category as righteous, just, and even pious. This is the continuing foundation of american exceptionalism, the trajectory of that social imaginary into our own time.

More than one historian writing in our contemporary times has called the Morgan tale “thrilling.” Jack Moore, author of the essay on the earliest printed version of the Morgan story, calls it: “One of the most exciting and enduring stories of pioneer adventure in West Virginia”[9] and identifies Morgan as still a hero in the state. And the extended Morgan family continues to have large reunions that recount their Davids, Zackquills, and Morgan Morgans, reunions that caught public attention even a century ago and more.[10]

The simplest and most unadorned version of the David Morgan killings is one recited by his son Stephen in a press interview in 1808 while his father was still alive. Stephen already addresses one aspect of that romantic exaggeration and puts the lie to another by simple omission—even as he engages in some exaggeration of his own.

Some historians have asserted that my father killed three Indians in the fight at our homestead in 1779. He was responsible only for the death of two Indians; they were of the Delaware Nation, and about thirty years old. One was very large, weighing about two hundred pounds; the other was short and stocky, weighing about one hundred and eighty pounds. My father (David Morgan) was six feet one inch tall, and at that time weighed one hundred and ninety pounds, about. It has been published that my father tomahawked and skinned the savages. This is not true. He left one Indian alive, but dying, and returned to the fort and to his bed, which he had left less than an hour before, where he remained for the remainder of the day. The oft’ made statement that he attempted to escape to the fort by flight is not true. He did not run a single step with the expectation of getting away from the savages. The running he did was done to gain an advantage over the enemy, and this he accomplished.[11]

Although Stephen fails to confirm it at all, many other versions of the story place Stephen (at about age 18) at the farm only seconds before the first murder. Indeed, most versions of the story place Morgan’s two youngest children on the site and have Morgan leaving the protection of the fort to check on his children and ultimately to rescue the kids.

It would seem that Stephen would certainly not fail to mention his and his sister’s presence that day and his father’s presumed heroism in rescuing both children from Indian attack. So we can readily dismiss this factoid as a later addition to the narrative intended precisely to increase its heroic value. Differing versions, while they might usually include the children-factor, add a number of other details that also seem to function as narrative justification for the killings and to heighten the heroic romance of what became the legend.

Some, but not all versions, speak of David Morgan suffering some illness requiring him to leave his sickbed to engage this enemy—again, seemingly added to increase the sense of the heroic. In some, Morgan has a vision while in bed at the fort warning him of the danger to his children. A couple of versions add a detail about Morgan finding the Indians actually inside his home.

The number of Indians killed also varies from two to three up to five.[12]For almost all of this, there is no real evidence whatsoever. Indeed, the stories that accompanied the “Iliff book” to its repository in Denver were even more the product of romance fantasy.

The earliest printed version of the narrative found its way into the U.S. Magazine in Philadelphia only a bit more than a month after the alleged event, yet even this early version must raise serious concern for historicity. The magazine posted a “letter” from an unnamed author writing from “Westmoreland” and dated April 26 and reporting the event happened about April 1.

Two problems arise immediately for the careful historian. First off, the letter is posted from “Westmoreland” and not from Prickett’s Fort or Rivesville, the immediate neighborhood of the event. The oral narrative must have travelled down-stream very quickly, no doubt, but what is the relationship between the reporter in this letter and those who were actually present for some parts of the event? Since Morgan was alone with the two Indian men he killed, he was the only surviving immediate witness. Others evidently rushed to the scene upon hearing Morgan’s report, but they could only function as eyewitnesses to the scene itself after the fact and the activities of the colonialists in killing the wounded man and deprecating both of their bodies—scalping, skinning, tanning the skins, etc.

So where was Westmoreland and how accurate might this letter writer’s version be? Westmoreland today is a county that is part of the Pittsburgh metropolitan statistical area, but in 1779 it covered a much larger area—including Ft. Pitt. It was the first county of Pennsylvania entirely located west of the Alleghenies, established in 1773.[13]

So the author of this letter could have lived in a smaller settlement south of Pittsburgh, closer to what is now the border between Pennsylvania and West Virginia, but still would have been some distance away from Prickett’s Fort and Morgan’s farm where these killings happened, which raises questions about the possible accuracy of the narrative on its face.

It could only have been third hand, at best. It is much more likely, however, that the letter came from the commercial and governing center of the county, from the county seat of Westmoreland County, a small colonialist settlement some 30 miles east of Pittsburgh called Hannastown. Hannastown was the crossroad for all euro-christian communication and business trafficking with eastern outposts like Philadelphia. It, and not Pittsburgh, was the early hub of government in western Pennsylvania, the location of all court proceedings and the hub for postal services.[14]

So the letter probably originated from a point 30 miles east of the river and 90 miles north of Rivesville. Since the author does not forward any written documentation, we are necessarily dealing with his writing down of a second hand oral account. Moreover, the letter author had by his claim written an earlier letter in which very little detail was yet shared. The second letter comes after the author was able to piece together more of the details, raising again the question of euro-christian colonial orality and historical accuracy.

The “letter” would have been a third-hand narrative at best, then, and had undoubtedly been shaped and enhanced by the reigning social imaginary of that time and place. Secondly, and perhaps more importantly, there is certainly evidence that the Philadelphia based editor of the magazine was a colonialist patriot zealot, a fanatic anti-Indian diehard who was capable of heavy handed editing of any text. Hugh Henry Brackenridge (who was still located in Philadelphia at the time) would have had plenty of rationale to edit (and emend) the “letter” extensively, and indeed he has a history (in retrospect) of doing exactly that. We will necessarily come back to a discussion of Breckenridge’s editorial proclivities when we turn to the death of William Crawford.

David Morgan, Surveyor

In his manner of living and defending himself and others, he [David Morgan] was no different from his contemporaries. I certainly would not class him an Indian-fighter, no more than I would class Jacob Prickett, Frederick Ice, or Nathaniel Cochran as such. He was a Christian, a patriot, a soldier, a surveyor, and a very good farmer, the profession of which he is most proud, and a loving, and most times, a too indulgent parent.

–Stephen Morgan 1808, speaking about his father[15]

So what was the socio-political milieu in which this murder happened? What shaped the social imaginary of the day?

There were several ways of generating great wealth in the colonial amer-christian period. The principal means all involved land in one way or another. Robert Morris, the main financier of the revolutionary war, made his wealth in land speculation, speculating in Native lands on the ever shifting frontier, as did a vast array of other “fathers” of America. Once the speculative purchases became less frontier-like and more euro-christian populated, the land speculators made huge profits in platting their lands for new towns and communities.

Lawrence Washington created the town of Alexandria, platting the land and then selling plots at an enormous profit. Ranking military officers stood to gain considerable reimbursement for their leadership by way of land grants from colonial, and then state, governments. At the head of armies roaming the frontiers, they also had opportunity to eye the best lands for investment and settlement. Trade accounted for considerable wealth, of course, but even trade is predicated on land as a resource to produce what is traded. Even the transatlantic trade in human bodies was ultimately predicated on occupying and using Native lands upon which those ensnared bodies were forced to labor.

About the most profitable job a young colonialist could have in colonial north America was that of surveyor, especially when appointed the head of a survey crew. The surveyor was working on the cutting edge of the advancing euro-christian frontier, and his work set him up for making very lucrative speculative land investments. It was a good setup for locating and claiming some of the best investment grade properties and generated great wealth for many of the U.S.’s founding fathers.

The enormous wealth of George Washington (until Donald Trump he was considered the wealthiest of all U.S. presidents—and the wealthiest american at the end of the 18thcentury) is directly related to these sorts of speculative land investments. Already at a very young age, Washington was sent out with a surveying crew working for what was a family business, the Ohio Company, a land speculation business started in the 1740s by a consortium led by Washington’s two older brothers, Lawrence and Augustin.

A good and trustworthy surveyor might also be compensated with a goodly share of the land speculated. Andrew Jackson was not a surveyor but aligned himself with a partner who helped him scope out and nail down properties across the southern frontiers that he had ravaged as the head of armies. Between Jackson’s prowess as conqueror and his surveyor/political partner, both men became enormously wealthy, a wealth that helped propel Jackson to the presidency.[16]

According to his son, David Morgan (1721-1813) was “a christian, a patriot, a soldier, a surveyor, and a very good farmer.” Stephen Morgan self-consciously resists labeling his father as an “Indian-fighter” in spite of the vast and romantic heroization of his father already in his own day. Looking back from 1808, Stephen muses that what his father did (killing Indians) is what everybody did in those early years of euro-christian invasion as these christian newcomers began settling what would become Marion and Monongalia Counties.

Yet, David Morgan is still widely remembered as “Indian fighter,” “Indian slayer,” and frontiersman to this day in West Virginia. Even the names “frontiersman,” “pioneer” or “settler”—rather than more accurate legal descriptions like “squatter” or “trespasser” on Native lands—signifies a noble endeavor in the building of America. At the same time, we should take careful note of Stephen’s classification of his father as surveyor, his early occupation and one he continued to practice from time to time even after establishing his farm in Rivesville.

There are two things to remark about surveying as a colonial occupation that can help sort out aspects of this colonial invasion. First off, surveyors in those colonial days were most always officials appointed by a territorial government or by land holding consortiums working with government issued proprietary land grants, meaning implicitly that they were plum jobs given out to young men from more highly regarded families.

Morgan came from such a family. As a result at the age of 25, Morgan was part of the famous team of surveyors who established the so-called “Fairfax Line” in 1746.[17] Some have even suggested that he was one of the “Gentlemen Commissioners” representing one side or the other, but I found no evidence to corroborate that notion.

It was, in any case, an illustrious group of some 40 men, including Peter Jefferson, Thomas Jefferson’s father, as one of the lead surveyors—representing the Virginia Colony with Thomas Lewis and Benjamin Winslow representing the grant holder, Thomas (aka lord) Fairfax.[18] Theirs was an arduous journey—for non Natives—across a rugged western landscape, still at that time a couple hundred miles east of the land Morgan would claim as his own by 1774. Then, in 1748 Morgan joined the young George Washington on that Ohio Company survey team into the Monongahela and Ohio Valleys, sent out by Lawrence Washington. So Morgan could well have walked the land more than twenty years before he moved in and staked his colonial claim to a lucrative farm.

Secondly, an appointment as a surveyor in the colonial frontier put that person in a prime position to capitalize big time with prime purchases of land. They were often the first, and most invariably the first formal, euro-christian parties to enter into frontier lands that were still in possession of their Native inhabitants, American Indian communities, and had not yet been claimed as the “private property” of any christian invader. Thus, even as the surveyor increased the wealth of the territorial governor or the land consortium partners who appointed him, he too stood to have the singular fortune of investing in prime pieces of frontier lands.

As a surveyor, David Morgan did not live in the same aerie as Washington or Jackson or even William Crawford (Washington’s partner in crime). Yet he too had ample opportunity to scope out his own homestead and the economic foundation to generate considerable (if middling) wealth. He had less interest, we are told, than his younger brother Zackquill Morgan, the builder of nearby Morgantown, in developing a land business and earning the greater wealth it might promise. He maintained a frontiersman persona, eschewing the more elitist sophistication of either his father or his brother, but was undoubtedly David’s early career surveying on the frontier that eventually brought him and his brother to the Monongahela River Valley.

We need to be clear that land was the principal medium of economic exchange in these early years of christian conquest of the continent—even as paper currency came more and more into play. One of the key areas of contestation in the early legislative congresses focused precisely on how to create legislation either to enhance the colonial landed elite or how to thwart those desires in favor of spreading landed property around more democratically.

Robert Morris and the Federalist party won those battles, but it cost them the presidential election in 1800. But then even those republican thinkers finally capitulated to the interests of the elites.[19] Surveying, land speculation, and colonialist greed for constant supply of new Native lands for euro-christian settlement, then, must play a role in the social milieu that allowed for such rapacious christian conduct of violence.

Trans Allegheny Frontier Enclaves

David Morgan was certainly not alone in his disdain for the aboriginal Peoples of this continent, nor, in the final analysis did he perpetrate these particular crimes alone. Moreover, what happened that day in the Monongahela Valley did not happen in a vacuum, but was intrinsically related to events exploding across the territories west of the Alleghenies. The land hunger of the christian invaders, it seemed, could never be quenched, even if it meant killing the current occupants of whatever lands they coveted.

By 1779 the colonialist invasion of the Monongahela Valley was just beginning, as the westernmost part of the ever expanding colony of Virginia. The first permanent colonists arrived only as late as 1774—in a flurry of colonial activity. The christian rite of the theft of Indian lands (by “Discovery” and conquest) was still not complete by 1779, giving rise to the need for building fortified retreats spaced through the territory in close enough proximity that colonists could run to their safety whenever the original “owners” of the land sought to contest the christian invasion and occupation.[20]

Morgan’s property claim, we are told, was about a mile’s distance from such a fortified retreat. And his “property” was legally secured, in the euro-christian legal discursive practice, by a treaty signed with Indian people, that is, Indian people nearly five hundred miles to the northeast—purporting to sign away land on which other Indian Peoples were living.[21]

The american frontier beyond the Alleghenies was a relatively small world in 1779—even as it was a huge territory. The euro-christian invasion was only just beginning, and their settlement enclaves were still quite small. Pittsburgh, for instance, was a village of only a couple hundred people, built adjacent to Ft. Pitt, which had its small military contingent.[22] The military garrison itself was only established in 1758 as a frontier outpost to both mark english “(christian) Discovery” claims to and restrain French aspirations for claiming that large, still heavily Native occupied, territory.

Not only were these frontier enclaves small and close-knit, but people on the frontier would have most often known each other, even when separated by considerable mileage. Morgan’s farm was some ninety miles south of Pittsburgh, but connected directly by the Monongahela River. More to the point, frontier settlement quite often involved larger extended families, so that much of the frontier was interrelated.

A couple hundred miles south of Morgan was another Quaker-born Indian killer, the famous frontiersman and surveyor Daniel Boone, whose mother was also a Morgan (Sarah). So the two were related, probably as cousins.[23] In the winter of 1788, Boone suffered a disastrous loss of a ginseng harvest in a rafting accident on the river near Morgan’s farm and spent a week boarding with his cousin.[24]

Would David Morgan have had acquaintances in Pittsburgh? Indeed, one key colonialist, a continental army officer and settler there, had worked with Morgan ca 1748-50 on that colonialist surveying detachment in the Ohio Valley with the young George Washington[25] and had squatted a farm near Pittsburgh. That old acquaintance, (Col.) William Crawford, would lead a failed invasion of Ohio League territory three years later in 1782 resulting in his death.

At the same time, a distant relative, George Morgan, was serving as Indian agent at Ft. Pitt, and they would certainly have been acquaintances.[26] Moreover, David Morgan, as the son of Col. (Rev.) Morgan Morgan, came from a relatively high-status and respected family. Morgan Morgan, a welsh immigrant, came to Delaware with an appointment to the crown council of the colony. He is widely considered the first euro-christian to settle Indian lands in what is today northeastern West Virginia, in Berkeley County, in 1731.

By 1734 the area was being flooded with euro-christian immigrants, particularly by a large influx of Quakers, and that same year, Morgan is listed as a founding member of the Hopewell Monthly Meeting of Quakers.[27] All of these relationships become important in describing the racialized socio-political milieu of euro-christian enclave at Rivesville, Virginia Territory.

David Morgan and his progeny—like most of their invading christian settler neighbors—certainly considered the Indian peoples of the Virginia frontier to be something less than human, certainly less than themselves. His son, Stephan Morgan, sheriff of Monongalia County called his father’s victims “savages,” although he also records that his father had learned at least three Indian languages, “Delaware, Shawnee, and Wyndotte [sic],” three of the languages of the Ohio Valley League, an alliance engaged in resistance to the further erosion of their Native land base.[28]

And we, living with a much greater appreciation for the complexity of these languages (representing two distinct language families) might allow that he may have learned bits and pieces of each. In any case, learning Native languages, especially in the late 18thchristian century, would have required a certain intimacy with those Native communities—belied by his evident hatred and fear of Indian people.

This adds a different complexity to the social milieu. Namely, in spite of knowing Indian people and interacting with their communities enough to learn some of their language, the social imaginary that captured David Morgan was one of displacing those same Indian people and taking over their lands as euro-christian “properties.”

Washington and Land Speculation: Treaties and Law Be Damned

In 1763 after the French were defeated both in Europe and in north America, an Algonquin alliance under the leadership of Pontiac responded to the loss of their French allies and the continued threats to their homes by attacking the anglo-christian settlements that were encroaching west of the Allegheny Mountains. Indian resistance forces succeeded in capturing most of the forts with the exception of Fort Pitt. While british military might finally overcame the Native resistance movement, opening western Pennsylvania and even the larger Ohio Valley to euro-christian settler invasion, that victory was thwarted by a nearly simultaneous royal edict from England, the proclamation of 1763.[29]

In response to the fierce Native resistance, Britain’s royal proclamation that fall was an attempt to separate the euro-christian settlers from Native Peoples’ communities. It prohibited any settlements west of the Alleghenies and forbade any non-governmental purchase of lands from Native Peoples. It even forbade territorial governors from making land grants in the region.

Needless to say, this created a great deal of resentment among euro-christian colonialists on that american frontier, including, no doubt, among land speculators like George Washington. Indeed Washington’s correspondence with a key co-conspirator and land surveyor based in Pittsburgh (a small village already settled west of the Alleghenies), is illustrative.

In direct defiance of the law, Washington directed his associate, the infamous Indian-killer, frontiersman, surveyor and land speculator William Crawford, to locate on his behalf choice pieces of land for investment purposes. In a 1767 letter, Washington begs Crawford’s strict confidentiality in their land dealings, while promising him a goodly share in the bounty: “I woud [sic.] recommend it to you to keep this whole matter a profound Secret.” The letter spells out considerable detail:

. . . I can never look upon the Proclamation in any other light (but this I say between ourselves) than as a temporary expedient to quiet the minds of the Indians. It must fall, of course, in a few years, especially when those Indians consent to our occupying those lands. Any person who neglects hunting out good lands, and in some measure marking and distinguishing them for his own, in order to keep others from settling them will never regain it. If you will be at the trouble of seeking out the lands, I will take upon me the part of securing them, as soon as there is a possibility of doing it and will, moreover, be at all the cost and charges surveying and patenting the same . . . . By this time it be easy for you to discover that my plan is to secure a good deal of land. You will consequently come in for a handsome quantity.[30]

Did Washington, the exceptional american hero, know that he was blatantly violating the law? Did he know he was engaged in treaty fraud? His own words seem to make all that clear. He goes on to invoke Crawford’s silence and confidentiality:

All of this can be carried on by silent management and can be carried out by you under the guise of hunting game, which you may, I presume, effectually do, at the same time you are in pursuit of land. When this is fully discovered advise me of it, and if there appears a possibility of succeeding, I will have the land surveyed to keep others off and leave the rest to time and my own assiduity.[31]

Then only three springs later, Washington joined Crawford, as they teamed up on a land scouting excursion to the Ohio River in the area around Point Pleasant. This was four years before Dunmore’s expedition—which included a company commanded by Crawford—which conquered Native Peoples there and secured the territory for euro-christian occupancy. Washington and Crawford were already looking for suitable investment property—ostensibly locating suitable lands as grants for veterans in Washington’s Virginia Regiment as well as for personal investment.

Edward Redmond reports that their joint effort resulted in a 64,071 acre grant,[32] but nearly 30 percent of this grant was patented in Washington’s name as personal property.[33] In this context we should note that by the time of Washington’s death (1799), he still owned 45,000 acres of land west of the Alleghenies, and that not counting the considerable acreage he had sold (at enormous profit) in projects of building frontier towns.

Crawford’s Demise and Hugh Henry Brackenridge, Editor

It is not insignificant that this is the same William Crawford who would be famously executed by the Ohio League in Hopocan’s Lenape village in 1782, after a disastrous attempted euro-christian attack on the League’s villages on the Sandusky River. This is three years after what Lucullus McWhorter calls “the Morgan-Indian tragedy at Pricket’s Fort,” yet it is not unrelated in interesting ways.[34]

Crawford’s execution was widely publicized in the colonial american frontier world, markedly in one particular published report.[35] The editor and publisher of the report is the same editor and publisher, Hugh Henry Brackenridge, who published the April 26, 1779 “letter” about the Morgan affair, having moved in the interim to Pittsburgh.[36] Moreover, as we shall see, Brackenridge was both a provocateur and a practiced liar of the highest order.

Brackenridge, a scottish immigrant as a child, was a diehard american patriot who wrote heavily romanticized patriotic poetry and drama. He graduated from Princeton with classmates James Madison and Philip Freneau, taught school briefly, was ordained as a presbyterian minister and served as one of Washington’s chaplains in the Continental Army—preaching fiery patriotic sermons. He went on to read law before settling in Philadelphia and pursuing his interests in publishing.

After his publishing venture failed to attract the gentry-elite of the capitol, Brackenridge abandoned Philadelphia for the tiny but what he thought the more wealth-and-fame promising outpost of Pittsburgh, where indeed he did go on to considerable fame and fortune. His accomplishments included starting what became the Pittsburgh Gazette and a school that is today the University of Pittsburgh. A failed politician who served one term in the U.S. congress, Brackenridge went on to become a justice of the Pennsylvania supreme court.

An incendiary propagandist for the revolutionary war, Brackenridge was particularly keen on fueling the war on the western front—against Indians. His publishing of the so-called captivity narrative of one of the euro-christian prisoners held with Crawford—but who managed to escape—is a prime example of this political urge.

I want to argue that his publishing of the Westmoreland letter recounting the Morgan killing of two Indians four years earlier is of the same propagandistic genre. Brackenridge found in the spectacular death of William Crawford, Washington’s old partner in the land speculation business and a citizen of Westmoreland County, a vehicle for pressing his anti-Indian propagandistic aims.

In late May 1782, Crawford led an army of about 500 deep into Ohio Native territory with the intention of surprising and destroying the Ohio League towns on the upper Sandusky River. It was just another piece of Washington’s strategy of fighting the revolution on two fronts: one against the English in the east; the other against Native Peoples in the Ohio Valley, the so-called western front. Ultimately, the League got notice of the attack and were well prepared to intercept Crawford and his army, defeating them handily. While a great many of Crawford’s men managed to escape during the rout, a contingent including Crawford were captured and taken to the main Lenape town. Crawford was executed following a day-long trial before one of the key governing councils (i.e., the women’s council) of the town.

One of those captured with Crawford, the regiment’s surgeon, Dr. John Knight, did manage to escape and make his way back towards Pittsburgh, where he functioned as an eyewitness to Crawford’s death, but his is only one of many eyewitness testimonies, both Indian and euro-christian. Brackenridge almost immediately imposed himself on the invalid’s bedside to get his account of the execution of Crawford.

Writing less than a month after Knight was found and carried into Fort McIntosh on a blanket, “injured, barely coherent, and starving,”[37] Brackenridge insists that Knight wrote out his own account. We know this to be a falsehood, since as Parker Brown notes Brackenridge himself admitted as much some years later.[38]

Yet, the historical accuracy of the Brackenridge text had gone largely unquestioned until the Brown’s analysis. Brown clearly demonstrates that Brackenridge engaged in heavy-handed editing in order to transform the surgeon’s tale of woe more expressly “into a piece of virulent anti-Indian, anti-British propaganda calculated to arouse public attention and patriotism.”[39] Parker is very convincing in showing what Brackenridge as editor deleted from Knight’s tale and what he added:

The middle portion is most historically suspect. Here the editor had several objectives in mind when he polished his notes. He desired, first, to produce a popular, salable story. He also wanted to stir the western populace into such a rage that it would immediately rise up to turn back marauding war parties and revenge the tortured commander, Col. Crawford. In addition, he wished to shame eastern politicians so that they would release more government troops for frontier duty. To do this, Brackenridge accented every gruesome aspect of Crawford’s ordeal. In so doing, he ignored important Indian motivations and circumstances, omitted significant recollections, and unjustly besmirched the character of Simon Girty, the British agent. (Parker, 55)[40]

While Brackenridge’s narrative became the celebrated frontier romance, persistently reprinted and sold out until after the Civil War, there were plentiful other accounts against which Brackenridge’s narrative can be compared. Fortunately, Parker Brown has done some of that task for us. Having devoted considerable publication energies writing about the Crawford incident, Brown is able to surface a number of other early reports on the Crawford execution, several even quoting Knight.

By comparing accounts, for instance, he is able to ascertain that Brackenridge has falsified the sequence of events, quite evidently to satisfy his own propaganda needs. Brackenridge spends no energy in exploring why the Natives dealt so harshly with Crawford other than his usual claim that they are a cruel and barbaric race—thus, ignoring the Goschocking (Gnadenhutten) Massacre of only a couple of months prior to Crawford’s military adventure.

Knight undoubtedly reported to Brackenridge that Crawford’s trial before the women’s council explicitly made the connection between his sentence and the Genocidal murders at Gnadenhutten, since we have other reports of Knight’s testimony from others.[41] Rather, Brackenridge chose to erase that connection in his published account of Knight. By shifting the sequence of events he avoids having to report either Crawford’s formal trial or the Native reasoning for their execution and works to conceal the connection between the two, leaving his readers with a clear impression of savagery on the part of Native Peoples.

He manages to extend Crawford’s march under guard by a full day in order to skip over a full day’s activity the day before the execution, namely Crawford’s formal trial before the Indian (women’s) council. Parker notes:

…the editing would be undiscernible were it not for the July 6 letter of Maj. William Croghan. In it, Knight is quoted as saying that he and Crawford began their return with guards to Sandusky two days after their capture rather than three days, as the narrative indicates. He also said that they were confined at Pipe’s Town the night before Crawford’s torture rather than some miles away, a fact corroborated by Indian sources. [Parker, 57]

It is well documented that Crawford received a trial before being executed, a fact that Brackenridge doggedly erases from his record. On June 10tha council, the Clan Mothers’ Council, in Hopocan’s Lenape town, spent long hours hearing evidence and debating Crawford’s crimes before passing sentence on him.[42]

Crawford, in other words, did have a formal hearing, the equivalent of a euro-christian judicial court trial. Reporting this fact would deprive Brackenridge’s narrative of some of its propaganda force. Indeed, Brackenridge has intentionally falsified his telling of Knight’s story to increase its propaganda force!

Moreover, in falsely defaming Katepakomen (Simon Girty) he further falsifies the evidence in favor of using his rhetoric to inflame the passions of amer-christian colonialists (Brown, 58, 59). Quite to the contrary of Brackenridge’s text, Katepakomen, a long-time friend and associate of Crawford’s, was appointed to serve in this Council hearing as Crawford’s “Speaker,” his advocate (Mann, 172). Again, Brown concludes:

All charges against him were aired. The surgeon surely told Brackenridge this, but how could the narrative mention the council without stirring curiosity as to what transpired? Readers were therefore kept ignorant of the council and its deliberations. (Brown, 57)

Crawford was taken to this particular town out of explicit deference to the Lenape precisely because of their loss, the genocidal massacre at Gnadenhutten, at the hands of another military foray led out of Pittsburgh only two months prior to the ill-fated Crawford campaign. We should note for starters here, however, that it was Crawford who initiated the most recent military encounter. He led a large army, under orders from a commanding general of the Continental Army, from Pittsburg into the Ohio Valley.

This was the remaining homeland of the Ohio League (Seneca, Wendat, Lenape, and Shawnee Peoples), and indeed, this was the third major american colonialist attack on the Lenape inside of four years. It had already firmly convinced the Lenape to abandon their longstanding attempt to remain neutral in the British/American war and forced the Lenape to move ever closer to the other League villages.

Of more immediate significance, however, is the historical fact that Crawford’s expedition against the Sandusky towns came so soon after Crawford’s second in command, David Williamson, had perpetrated that vicious Genocide against an american allied Moravian christian Indian village at Gnadenhutten.[43] These pacifist christian Indians were overwhelmingly Lenape, and in spite of their conversion they were still beloved relatives of those Lenape on the upper Sandusky.

This accounts for the principled decision to transfer Crawford to Hopocan’s Lenape town for trial and execution. The wounds were still very raw from that euro-christian brutality, from the murder of ninety six of Hopocan’s people—some 28 men, 29 women and 39 children were murdered in cold blood, execution style, by Williamson and his men. Three months later Williamson escaped capture. Crawford was not so lucky and paid the price for Williamson’s indiscretion. The Lenape explicitly made the connection between the Genocide at Gnadenhutten and their trial and execution of Crawford.

Brackenridge just as intentionally concealed that connection in order both to inflame his public against Indian folk generally and to help salve the euro-christian conscience by erasing that stain of guilt. Parker Brown is absolutely correct in his analysis here. Indeed, Brackenridge seems to see the death of Crawford as an opportunity to move the attention of the amer-christian public beyond any remorse they might feel for the Gnadenhutten Massacre and to redirect attention to his own project, one of identifying Indian peoples with barbarity as blood thirsty savages.

At the same time, it should not pass without notice that this was not Crawford’s first outing in military uniform against Native Peoples on their own land. He had fought in the Ohio valley war of the british against the french, the so-called french and Indian war—as a member of the ill-fated Braddock expedition; fought again in the Pontiac War. He led a virginia regiment early in the revolutionary war, seeing action on that western frontier against Native Peoples. But most memorably for the Native alliance in the Ohio Valley, he had been with Dunmore’s expedition at Point Pleasant in 1774 and led the gratuitous attack that destroyed the undefended Salt Lick Town after the decisive military encounters had virtually ended Indian resistance.

This, we will remember, was precisely the territory he and Washington had reconnoitered only a couple of years before as potential investment property. A euro-christian captive of this community, Jonathan Alder, told an account of the attack. Community members remembered and told a terrifying account, of what Andrew Lee Feight insists would be called “a monstrous war crime” today: “…the killing of innocent civilians who ran in panic with their children and grandchildren as the Virginians shot indiscriminately at the villagers.”[44] Alder clearly reports that no armed fighting men were present in the village at the time. Needless to say, Indian Peoples in the Ohio Valley neither forgot nor forgave that criminal act on Crawford’s part.

Crawford’s execution was both dramatic and brutal, involving hours of torture. As he walked around the stake to which he was tied, he was shot 96 times with blank loads of powder, one for each of the innocents killed at Gnadenhutten. Brackenridge’s editorial handling of the incident, erasing the Gnadenhutten connection, however, is merely opportune propagandizing, intentionally inciting further terrorist activity on the part of the amer-christian population of western Pennsylvania and of the federal government itself. Because there are other reports that also quote Dr. Knight, we know that Brackenridge persistently falsified Knight’s story, his political and propaganda interests superseding any interest in truth-telling.

This brings us back full circle to Brackenridge’s publication of the Westmoreland letter about the David Morgan killings in May 1779, less than a month after the murders had been perpetrated near Rivesville, and raise anew for us the question of the letter’s truth value, since we only have Brackenridge’s published account of the letter and do not have the autograph copy. How much of that letter is the original letter, and how much is heavy-handed editorial emendation from Brackenridge?

The Letter

By 1779, Brackenridge was in Philadelphia (and not yet in Pittsburgh) following his literary dream to publish the first american magazine, the United States Magazine, as a vehicle to advance his patriotic fervor. It was a joint venture with college classmate and fellow poet Philip Freneau, and it was published by the same Mr. Bailey (aka Francis Bailey) to whom Brackenridge sent the Knight and Slover narrative four years later from Pittsburgh.[45] So here is the narrative culled from that 1779 U.S. Magazine, embedded in a letter marked”Westmoreland, Apr. 26, 1779.”

“Dear Sir,

“I wrote you a note a few days ago, in which I promised the particulars of an affair between a white man of this county, and two Indians (sic): now I mean to relate the whole story, and it is as follows:

“The white man is upwards of sixty years of age, his name is David Morgan, a kinsman to col. Morgan of the rifle battalion. This man had through fear of the Indians, fled to a fort about twenty miles above the province line, and near the east side of the Monongahela river. From thence he sent some of his younger children to his plantation, which was about a mile distant, there to do some business in the field. He afterwards thought fit to follow, and see how they fared. Getting to his field and seating himself upon the fence, within view of his children, where they were at work, he espied two Indians making towards them: on which he called to his children to make their escape, for there were Indians. The Indians immediately bent their course towards him. He made the best haste to escape away, that his age and consequent infirmity would permit: but soon found he would be overtaken, which made him think of defense. Being armed with a good rifle, he faced about and found himself under the necessity of running four or five perches towards the Indians, in order to obtain shelter behind a tree of sufficient size.

“This unexpected manoeuvre obliged the Indians, who were close by, to stop where they had but small timber to shelter behind, which gave mr. Morgan an opportunity of shooting one of them dead upon the spot. The other, taking advantage of Morgan’s empty gun, advanced upon him and put him to flight a second time, and being lighter of foot than the old man, soon came up within a few paces when he fired at him, but fortunately missed him. On this mr. Morgan faced about again, to try his fortune, and clubbed his firelock. The Indian by this time had got his tomahawk in order for a throw, at which they are very dexterous. Morgan made the blow, and the Indian the throw, almost at the same instant, by which the little finger was cut off Morgan’s left hand, and the one next to it almost off, and his gun broke off by the lock. Now they came to close grips. Morgan put the Indian down, but soon found himself overturned, and the Indian upon him, feeling for his knife, and yelling most hideously, as their manner is when they look upon victory to be certain. However, a woman’s apron which the Indians had plundered out of a house in the neighborhood, and tied on him, above his knife, was now in his way, and so hindered him getting at it quickly, that Morgan got one of his fingers fast in his mouth and deprived him of the use of that hand, by holding it; and disconcerting him by chewing it; all the while observing how he would come on with his knife. At length the Indian had got hold of his knife but so far towards the blade that Morgan got a small hold of the hinder end; and as the Indian pulled it out of the scabbard, Morgan giving his finger a severe screw with his teeth, twitched it out through his hand, cutting it most grievously. By this time they had both got partly on their feet, and the Indian was endeavouring [sic.] to disengage himself; but Morgan held fast by the finger, and quickly applied the point of the knife to the side of its savage owner; a bone happening in the way, preventing its penetrating any great depth, but a second blow directed more towards the belly, found free passage into his bowels. The old man turned the point upwards, made a large wound, burying the knife therein, and so took his departure instantly to the fort, with news of his adventure.

“On the report of mr. Morgan, a party went out from the fort, and found the first Indian where he fell; the second they found not yet dead, at one hundred yards distance from the scene of action, hid in the top of a fallen tree, where he had picked the knife out of his body, after which had come out parched corn, &c. and had bound up his wound with the apron aforementioned; and on first sight he saluted them with, How do do broder, how do do, broder?but alas! poor savage, their brotherhood to him extended only to tomahawking, scalping, and to gratify some peculiar feelings of their own, skinning them both; and they have their skins now in preparation for drum heads.”

There are a number of issues here to which our interpretive analysis must be drawn:

- First of all, we need to note the immense attention to even the smallest details in the letter. The detailed description is inordinate for someone who was not even present at the site of the murders—the writer in Westmoreland. Suspicion should already be heightened that too many details were added in Philadelphia, rather than in Westmoreland or even at an oral traditions stage coming out of Rivesville. This already says something about the mindset of the publisher of the letter and the mindset of his public.

- That there were two Indian men on the scene seems apparent. We have Stephen Morgan’s word to that. That much seems unquestionable.

- Morgan would have been 57 years old. While that would not have disqualified him from battle or military service, it seems quite old for a single warrior to be choosing to attack an enemy alone in the open field, let alone two of them. That would mean that he chose a fight in which he was outnumbered. It is hard to imagine even euro-christian arrogance resulting in such brazen bravery.

- The identification of David Morgan as a kinsman of quite famous virginian military hero, Daniel Morgan, has been made persistently. It is patently false. To my knowledge this “letter” is the first instance of that claim having been made. This is undoubtedly Brackenridge’s editorial work, enhancing the importance of the event and his magazine story. No one close to David Morgan would have made that mistake or had any reason to manufacture the relationship. In later tellings, Daniel becomes the “estranged” younger brother of David. Brackenridge, on the other hand, was deeply involved in that war, having served as chaplain to the Continental Army and having functioned as an incendiary patriotic voice both as chaplain and as writer after that service. His seemingly intentional mistake here, and editorial insertion, would serve to enhance the romance of the narrative of the original letter.

- If there was a general fear of Indian raids that brought the surrounding enclave in to the safety of the fort’s confines, why in the world would a “doting father” (Stephen Morgan’s description) send his “younger” children out a mile from the fort on farming chores without himself? This simply fails to ring true; it would have been irresponsible parenting, to say the least. Later versions attempt to explain this discrepancy away by insisting that Morgan was ill at the time, but Brackenridge’s “letter” fails to indicate anything of this nature. Then we have Stephen Morgan’s abbreviated version in which there is no mention of children (namely, himself!) being out at the farm at this dangerous moment and no mention of any illness on David’s part. The two children most often mentioned as having been sent to the farm are Stephen and Sarah. Stephen would have been not yet eighteen; Sarah thirteen or fourteen. Now these teenagers are certainly not 21stcentury teenagers. We know that Lewis Wetzel was eighteen when he publicly killed a Lenape man who was trying to negotiate peace with his commanding officer, Col. Brodhead. Wetzel, still young, was an accomplished frontiersman and professed Indian killer, as was Jesse Hughes and Stephen’s cousin Levi Morgan. Wetzel, Hughes, and Levi Morgan would have been roughly the same age group as Stephen. Surely Stephen would have been armed; perhaps even Sarah. After all, these euro-christian invaders certainly felt the need for constructing forts like Pricketts. Why would an older man decide to square off with two much younger and stronger adversaries while he instructs his perfectly capable son to run? Why wouldn’t they have fought side by side—as so many other stories depict father and son in battle during this time? And this is especially significant given that the old man was outnumbered by two armed young Indian men. It seems apparent to this reader that Brackenridge must have invented the children-present part of the narrative. Again this would have functioned to enhance David Morgan’s heroism, to heighten the sense of heroism of the amer-christian over against the hated enemy. Stephen omitting any mention of his or his sister’s presence is critical here. He surely would not have omitted that fact if it were indeed the case. Stephen was strong enough to farm; surely he was trained in military arts living that deep in frontier territory. Lewis Wetzel, we know, was carrying a rifle by age thirteen. Surely, Stephen would have been armed that day. And certainly he took on military responsibilities as sheriff of Monongalia County early in the next century. Could this have been an invention that crept into the oral tradition before it got to Brackenridge—to explain away David’s rashness in taking on two Indian adversaries? I suppose that is possible, but it seems to me improbable that early in the oral tradition process. More likely, in my opinion, the urbanite Brackenridge was the inventor of this detail. Having lived his life much further east, he would not have the intimate knowledge of the technical difficulties of frontier living in squatter enclaves—at least not at this stage of his life. The incongruity would have been far less noticeable to him.

- Then we must deal with the fact already alluded to that there was only a single surviving eyewitness to the events that unfolded—either sans children or after they run for the fort. But remember, Stephen does not place himself on the scene at all. It certainly would have helped his description if he could have provided eyewitness testimony at least to the presence of two Indian men. So ultimately, we—meaning we modern readers, and those who were secondarily at the scene after Morgan’s action in the field, and even Brackenridge—have only David Morgan’s word for what happened that day! And in reality we do not even have Morgan’s word, since he did not write about the incident, nor is he recorded as speaking about it directly. As the first written account, Brackenridge’s “letter” would then have become a principle source for a still congealing oral tradition.

- There are at least two instances in the letter that show editorial enhancement for the sake of making the narrative more pointed in its anti-Indian-ness: “The Indian by this time had got his tomahawk in order for a throw, at which they are very dexterous.” The appearance of a tomahawk reads naturally as part of a report. The addition of the racial stinger at the end of the sentence, however, is undoubtedly an addition: “…at which they are very dexterous.” Not yet living on the frontier, Brackenridge simply does not know that Lew Wetzel is just as dexterous, for instance, but to this day the symbol of a tomahawk is used as a racially identifying device.[46] The addition is intended to heighten the racialization of the enemy in the minds of his Philadelphia authence. The same seems the case for the following sentence which includes this addition: “yelling most hideously, as their manner is when they look upon victory to be certain.” It certainly seems unlikely that Morgan, recovering from relatively serious injury and loss of blood, would be interested in this detail as it is written. Morgan may have remembered a yell. The Westmoreland traditior might have included a yell. But here again, the narrative is significantly enhanced to widen further the gap between christian (clarified explicitly as White) and a savage Native. A further emendation seems to accompany the letter’s report of the skinning of both victims. That they were disfigured this way is not the question. That much is undoubtedly the case. But the act of skinning seems to have shocked even this diehard Indian hater: “…to gratify some peculiar feelings of their own, skinning them both….” After all, Brackenridge is a city boy, a college graduate, a minister, etc. Skinning a victim would not be a usual mode of thinking in his urbane world, in spite of his need to deprecate Indian enemies.

- It seems clear that Brackenridge edited this letter with a similar heavy hand, as he did demonstrably with the Knight report.

- So what actually happened? Here we can only suggest possibilities based on what we do know about the historical context. I am offering my reading of the incident, trimmed of all the ornamentation that has attached itself.

- Two Lenape men were out one day wandering through their land, through their former home perhaps, or maybe they were neighbors. Maybe they were hunting. We don’t know. But David Morgan sees them. Or more likely, he sees one man not realizing there are two of them.

- Maybe these men live in an Indian community nearby. Friendly Indians. Like the Conestoga Indians who continued to live peacefully with their new neighbors in Pennsylvania and whom the presbyterian Paxton Boys dispatched in their rage at all Indians two decades before. The widely reported speech of the mortally wounded man (“How do do broder, how do do, broder?”) might be an indication that we are indeed dealing with a christian convert. That a Lenape might know some english language is not surprising, but the use of the english word “brother” as an address is. While the usage is more common street language today (Howdy, Bro! or He’s my bro.), in 1779 it would still have been a more religious usage. The “how do” part of the questions sounds odd in today’s english usage, but it accords with usage of the time, dating to 1680, particularly in scottish usage.

- If these two men were actually out to engage in active Indian resistance, surely they would have been much more attentive and careful. The euro-christian romance, however, makes every effort to cast Indian peoples as inept, lacking in proficiency. For better or worse, we can only guess at the intentions of these two men; likewise we can only guess at what might have gone through Morgan’s mind as he saw the first of the two men.

- My own guess is that Morgan, seeing only one man at first, simply decided that this was an easy kill, another note in his bible. Having a reputation as skillful with a rifle, he drew a bead and shot the man forthwith. Indeed, this would have been a pro forma action in Morgan’s frontier world of euro-christian domination. He certainly knew the young Jesse Hughes, his own nephew’s serial murder of Indians was already a legend in that part of the country. But to Morgan’s surprise there were two men in the field, not just one. Having fired his (single-shot, muzzle-loading) rifle, he was suddenly in big trouble. Lew Wetzel was famous for being able to reload while at a full run, but that was a scarce talent. Morgan was 57 and less physically inclined than young Wetzel. Now it became hand to hand combat. That Morgan won that struggle is as much luck as anything. How much of the story to believe is difficult to ascertain, of course, but there does seem a weight of evidence that there were two men killed that day. My argument, however, is that Morgan did not expect to have to deal with a second person after killing the first. The first killing was cold blood. The second has some element of self-defense, but I would argue that it was murder all the same. Both men should have survived to be with their own children that night or soon thereafter.

The essential American soul is hard, isolate, stoic, and a killer.

—D.H. Lawrence

In David Morgan we do not quite see the dedicated, single-minded Indian-killer that we see in his upstream colleague Jesse Hughes or in his nephew Levi Morgan (Zackquill’s son). Nonetheless, David brags in his family bible that was able to kill seven Indians in his lifetime. His son Stephen assures us that this was before the two he killed on that infamous day that insured David’s frontier hero status. Levi Morgan’s killings are numbered, we are told, in the hundreds, and like Hughes or Lewis Wetzel further north near Pittsburgh, Levi’s killings mostly happened outside of the context of military battles. These men were dedicated serial murderers, to use Barbara Mann’s designation.

David Morgan does reflect the general attitude of the invaders towards the aboriginal Natives whom they were displacing. Hughes, Wetzel, and Levi Morgan were held in the highest regard for their records of slaughter; they were already romanticized in their own day by their frontier neighbors. When Col. Daniel Broadhead, leading an army of half Continental regulars and half locally recruited militia volunteers, promised safety to a Lenape delegation to cross the river and negotiate peace with the americans, Wetzel interrupted the peace process single-handedly. As the two Lenape disembarked from their canoe, “Lew Wetzel… walked up behind one of them and sank a tomahawk into his skull.”[47]

While Wetzel’s killing ensured the continuation of warfare between the two sides, an enraged Broadhead was powerless to discipline Wetzel because of the high regard the volunteers had for the man. Broadhead would have lost half of his army forthwith. Wetzel, like Jesse Hughes, killed Indians out of pure hatred but also simply as sport.[48]

Describing a later incident in Wetzel’s life, George Carroll avers, “No action could illustrate any better what a skillful and remorseless terrorist Lewis Wetzel had become by his mid-twenties.” Carroll goes on to argue, “The task of an adequate scale of judgment for assessing the homicidal actions of Lewis Wetzel is difficult to establish apart from the frontier society he inhabited.” Indeed, the enclaves of christian settler-invaders may not have widely emulated these killers, but they depended on them to help build their own security living on stolen land. Thus, they were widely admired and glorified in the euro-christian frontier romance narrative.

Likewise, after the Rivesville killings David Morgan’s fame was ensured. What actually happened that day on the farm we will never really know for sure, but it looks like a simple case of murder times two. He could aim his rifle at what he thought was a lone Indian roaming his farm and kill him in cold blood simply because, as son Stephen reports, that is what euro-christian squatters on the frontier did: “I certainly would not class him an Indian-fighter, no more than I would class Jacob Prickett, Frederick Ice, or Nathaniel Cochran as such. He was a Christian….”

So killing the first of these men was merely a habitual response, and alone it probably would not have earned him the fame that resulted in his hand to hand fight with the second man.

While Slotkin calls these frontier narratives “a lethal national mythology,”[49] West Virginia historian George Carroll, among others, has a very different take:

The plea of humanity notwithstanding, Crevecoeur’s testimony is clearly suggestive of how effectively unnerved much of the American rural population was, and how much food producing western territory was depopulated by guerrilla warfare which in reality employed few armed forces. Would that the large armies of the Revolution had been as effective.[50]

He goes on to warmly cite novelist Zane Grey, who used the Wetzel personage to create several novels: “The border needed Wetzel. The settlers would have needed many more years in which to make permanent homes had it not been for him. He was never a pioneer; but always a hunter of Indians.”[51]

That, too, was Morgan’s nephew Levi and Jesse Hughes, but David Morgan was a farmer: “…the profession of which he is most proud,” reported Stephen. Yet the Indian-killing romance around Wetzel, Hughes, Levi Morgan and others developed precisely among these farmers and their families. Their occupation of Native lands depended on the terrorism and easy serial murder of Indian people perpetrated by these Indian killers.

Meanwhile, journalist/politicians like Hugh Henry Brackenridge advanced the narrative all the more widely though their publications—insuring that future euro-christian writers like Zane Grey would perpetuate a variety of variant narrative romances of conquest well into the 21stcentury. It is clear from Brackenridge’s later publications that his virulent anti-Indian sentiment and rhetoric continued until late in his life.

By 1792 he published a front page article in the National Gazette pressing the government of the new republic to continue its military attacks on Native Peoples in the Ohio Valley.[52] That article argued the national government had an obligation to defend its frontier citizens as they penetrated ever deeper into Native territories. “The government,” Brackenridge argues is “bound to give peaceable possession of the soil,” that is, Indian soil, to its citizens.

As Patrick Spero argues, Brackenridge held an attitude towards Native Peoples that was shared across the frontier—but one he in no small way helped to entrench through his writing. He found Indian Peoples to be inherent and perpetual enemies who are a constant threat to invade—a curious reversal of actualities, a kind of psychological projection that Freud would have found interesting.[53]

The best defense, Brackenridge finally concludes, would be a military offensive, “penetrating the forests, where they haunt, and extirpating the race.”[54] Spero concludes, “Such an offensive posture, framed by the idea of a permanent Indian enemy constantly threatening invasion, meant that the frontier was to be an expanding and active zone of military operation.”[55] David Morgan, and his history of murdering Indians, is deeply embedded in this frontier christian narrative.

American history is overflowing with fictional, historical, legal and religious narratives invented by the euro-christian colonialists, invariably casting Native Peoples in a negative light and functioning to justify euro-christian conquest and occupation. Moreover, the colonialist academic histories that ensue from these narratives are inherently steeped in the romance of this history even as academics make their usual claim to objectivity.[56] It is the ground level stuff of contemporary american exceptionalism.

So jamaican scholar David Scott should not surprise us when he argues that the vast majority of academic histories (and he would include all european histories in his critique) produced during the era of modernity are written in what he identifies as the romance genre.[57] Indeed, much of christian colonialist history, past and present, paints an idyllic Bierstadt portrait of a bucolic fantasy community bathed in a warm sepia light—until the Indians appear.

This means that we must regularly invoke a hermeneutic of suspicion whenever we engage historical interpretation of any narrative rooted in this colonial past. As the saying goes, history is written by the victors, and in this case the victors are the christian colonialists who continue to steep their histories in the veil of romanticism.

Scott’s corrective is to insist that histories should be written as tragedies. An english interpreter does some of this work for modern american folk. D.H. Lawrence, writing in Taos New Mexico in 1923, put it this way: “But you have there the myth of the essential white America. All the other stuff, the love, the democracy, the floundering into lust, is a sort of by-play. The essential American soul is hard, isolate, stoic, and a killer. It has never yet melted.”[58]

As we watch an America today wrestle with the continuing specter of confederate civil war statues and persistent calls for their removal and some memorializing of that hurtful past, we cannot help but ask about amer-christian people’s history of violence with regard to American Indians. How can we memorialize that past in all of its quagmire depths and complexities without recourse to the genre of tragedy?

I began this research project with a book of christian history that was bound in leather tanned from the flayed hide of a murdered Indian man (i.e., a Lenape man), a book that was held as a treasure and displayed with honor for 80 years in the library of a methodist school of theology as a special trophy in their rare book collection. Iliff school of Theology did the right thing in 1974 when they separated the cover from the book and surrendered it to the Colorado American Indian Movement for burial—even if they did so by invoking secrecy, intentionally swearing Colorado AIM to secrecy as part of the deal, in order not to offend their funding base.

One of the unanswered questions had to do with how the book ended up in a methodist institution. The book had been a gift from a local methodist minister with connections to west Virginia. But how did a methodist minister come to possess the book? Part of the answer lies in the unfolding history of quaker born David Morgan, reputed to have helped build the first episcopal church in Fairmont.

By 1786, however, Morgan had become a methodist—along with several neighbors and family members.[59] In this, he is much like quaker born John Evans, the Colorado territorial governor associated with the Massacre of Cheyenne and Arapaho people at Sand Creek in 1864. So we come full circle from methodist to methodist. But lest we be too hard on methodists, we remember that quaker born Daniel Boone became baptist by the end of his life.

Brackenridge and then Andrew Jackson were presbyterian; other prominent anglo-christian conquistadores were puritan or episcopalian. The tragedy here is that religious affiliation (i.e., christian affiliation), even with pacifist leanings, could not protect the original peoples of the land from displacement, land theft, murder, terrorism and genocide.[60]

It was just too deeply ingrained in the behavioral habits and conceptual imaginary of the christian invaders. The next step, initiated from the beginning, as it were, was to ingrain these behavioral habits in legal codices and in intellectual discourses that provided some clear excuse for christian behavior. That would lead us logically into a critique of (episcopalian) John Marshall’s unanimous decision in the Johnson v. M’Intosh case on the Doctrine of (christian) Discovery in 1823, 44 years after the Morgan killings.[61]

Conclusion