Sarah Huckabee Sanders’ condescending dismissal of congressional representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (during an interview with Fox News), went largely unnoticed during a week dominated by the latest rancorous national debate. It is difficult to imagine that anyone missed seeing mediated images from every imaginable angle and released over a period of several days, capturing a now infamous encounter between Indigenous activists, Black Hebrew Israelites, and a group of mostly white high school boys from Covington Catholic school. The confrontation took place just after the Indigenous Peoples’ March in Washington, D.C.

Ocasio-Cortez (AOC), one of two female democratic socialists and the youngest person ever elected to a House seat, admitted to writer Ta-Nehisi Coates at an MLK NOW event on January 19, that she is concerned about environmental instability and climate change; she and “other young Americans” she reported, “fear the world is going to end in 12 years if we don’t address [it].”

Huckabee Sanders, in response to the dire prediction, did not hide her scorn.

Look, I don’t think we’re going to listen to her on much of anything, particularly not on matters we’re gonna leave in the hands of a much, much higher authority, and certainly not listen to the freshman congresswoman on when the world may end. We’re focused on what’s happening in the world right now.

It is no wonder that AOC’s warning and an official response to it were overshadowed during a tumultuous week of polemics and conflict; in fact, it was Huckabee Sanders’ observation (in reference to Nick Sandmann, the smirking boy facing Omaha elder Nathan Phillips in the videos), that “I’ve never seen people more happy to a destroy a kid’s life,” that became the preferred soundbite for an administration peddling them on a minute-by-minute basis.

What is unfortunate is that mediated images from the encounter in front of the Lincoln memorial, dispersed worldwide and dominating social media for days, might have led to useful conversations about devastation and genocidal ill-effects endured by Native communities across these lands – resulting directly from over 500 years of the intertwined projects of missionization and colonization.

Predictably though, the opposite happened. Within hours of globalized dissemination, any opening for that had been successfully nullified, and any chance for authentic recognition of Indigenous concerns was extinguished. How and why one way-of-being is invariably imposed is the topic of this piece.

AOC, from the Fourteenth Congressional District of New York is a lightning rod and thorn in the side for the so-called political “left” and “right,” respectively. Her polemical style has reach — her suggestion, for example, that a 70% top marginal rate tax (on income over 10 million) be levied on American billionaires, evoked consternation and displeasure at the 2019 World Economic Forum in Davos.

Closer to home, her dash through Capitol Hill as she searched in vain for senator Mitch McConnell one day, during the fourth week of the longest government shutdown in US history, was delightedly captured by congressional reporters, then virally-shared via #wheresmitch.

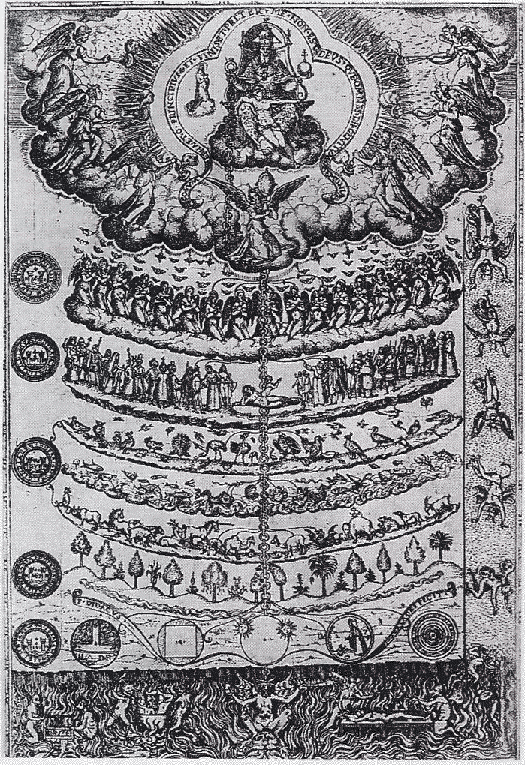

In response to the end-times prediction though, Huckabee Sanders put the young congresswoman in her place in what she and many Americans envision as a divinely-ordained cosmological hierarchy. Cognitive science theorists tell us that a metaphorical process forms via a basic level category that is then expressed in what Steven T. Newcomb (Shawnee/Lenape) and others have identified as an Up-Down image schema. It is intrinsic to a eurochristian worldview.

Following Tink Tinker’s work, my use of the term ‘eurochristian’ is not limited to people who identify as Christian, rather it is meant to encompass a shared ontology and orientation based on specific cognitive models that feature human-centric, chain-of-command conceptual categories. For those sharing this way-of-being in the world, “higher authority” is a cipher for a creator – a god-on-high that occupies the highest level in the cosmology.

You may be tempted to conclude that Huckabee Sanders and AOC could not be further apart in their views. After all, they represent prototypical political personas, while provoking high-spirited debate on both sides of the aisle. Granted, they are at ideological odds in obvious ways. What’s true though, is that they share the very same worldview.

Conceptual categories grounding a traditional Indigenous worldview are radically different. This might be nothing more than compelling if there was not so much at stake. The intensity of the debates around the incident in D.C. typifies the tension between two irreconcilable worldviews – that which I call eurochristian, and that of American Indian Peoples.

The incommensurability is predicated on difference, and there can be no resolution based on any attempt to homogenize, dilute, or ignore that difference. There is radical alterity that sharply defines these opposing cultures; at the heart of this incommensurability lie two distinct ways of relating to community.

Cognitive science theorists George Lakoff and Mark Johnson argue convincingly that “the mind is inherently embodied, thought is mostly unconscious, and abstract concepts are largely metaphorical.” What this means is that how you know the world depends on who you are – including but not limited to specific, familiar thought processes shared and exchanged within your specific culture.

One method of exchange is through language. Words that saturate thoughts, speech, even dreams, convey perceptions and function as a cipher. What’s more, our perceptions of the world around us are not arbitrary. Every experience we have is rooted in culture and community.

Understanding how we think is as important as what we do with what we think. I argue that since different conceptual categories are ontological building blocks for communities in opposition, we must understand how these categories form, and are (mostly) unconsciously held and reproduced from one generation to the next.

The Lakota phrase mitakuye oyasin,for example, translated by Lakota scholar Albert White Hat as “we are all related,”gives insight into a worldview that extends personhood to all living beings, where ontological distinctions between human beings and other-than-human beings are non-existent. Mitakuye oyasin describes relationships and responsibilities between human beings, animals, everything that moves. Whit Hat writes,

If you think about our concept of Mitakuye Oyasin, which means “we are all related,” it begins to make sense that an animal or bird or plant, as a relative, could help you…there is no mystery in our philosophy. There is no mystery and there are no miracles. Everything we do is reality based. We understand what we are doing, and we understand who we are working with every moment. We are working with our relatives. (36)

To describe this way-of-being using cognitive science terminology, Tink Tinker (Wazhaze/Osage) identifies an image schema – collateral egalitarianism – to present an Indigenous and non-hierarchical ontology of inter-relatedness.

Based on lateral social constructs, and predicated on dualism or complementary opposition, collateral egalitarianism recognizes the basic opposition in the everyday as gerund and balance-seeking, as opposed to fixed and static. This different way-of-being directly challenges what has been largely assumed to be true by non-Native peoples — there is “an absolute dichotomy between perception and conception. Lakoff and Johnson write,

The claim that the mind is embodied is, therefore, far more than the simple-minded claim that the body is needed if we are to think. Advocates of the disembodied-mind position agree with that.Our claim is, rather, that the very properties of concepts are created as a result of the way the brain and body are structured and the way they function in interpersonal relations and in the physical world. (37)

A way to identify radical contrast between cultures and also how image schemas become thoroughly embedded within disparate cultures is by exploring these differences through stories people tell themselves about themselves – stories that bring to life the contrasting up-down and collateral-egalitarian image schemas, indicative of opposing ontologies.

Huckabee Sanders, referring to a “higher authority,” and AOC’s retort, featuring scriptural references from the Hebrew bible, are propped up by tales about how about humans and other living beings came to inhabit this world. We will examine parts of that story and its stark contrast with a Lakota understanding of wakan – what White Hat translates as the power to give life and take life (31, 84, 175).

White Hat breaks down the term etymologically: kan, he says, is the cumulative power to give life and to take life. Kan is imbued with both good and bad potentialities. All living beings contain elements of this power and are related to each other in a non-hierarchical way. Wa indicates a subject. Wa and Kan together means that the living things of creation contain the power to create and destroy.

The following is what White Hat calls the Lakota origin story.

The origin story begins in darkness. ‘In the beginning’ was Inyan. And Inyan was in total darkness. And Inyan was soft. And Inyan was Wakan. Wanting to create life, Inyan constricted and began to drain blue blood, which created a disk around itself called Maka. Half of the disk was land and half was water; so the first life was Maka (earth) and Mni (water). Everything was blue, like the color of Inyan’s blood, but Inyan, Maka and Mni gradually separated the blue from the rest of creation and it became Mahpita To (the blue sky). The original name for this separation translates as ‘I am different,’ or Miye Matokeca.” (31)

Next, Inyan created Anpe Wi (sun), to make daytime (anpetu wi), and Hanwe wi (Hanhepi Wi) – the moon and the nighttime. Then came Tate (the wind). As each new creation came into being, there was another one created in the universe. Like everything that Inyan brought forth, it came in twos, because for all living things, in the world, there is a counterpart. For every being on earth, there is an identical other in the universe. Whatever you are doing on earth, the other you is doing that in the universe. Occasionally, that other one will send some energy down to you, and whatever you are doing at the time will get a little boost. (33)

The story describes a balanced correlation between two worlds – a balance, White Hat tells us, that is also found between earthly beings. For the earth, there is sky. For the night, there is day. For female, male. There are other important details.

As each new creation is given breath/life, they are not temporal, sequential events, nor are they hierarchically-organized. The process is an egalitarian emergence, balanced, and full of reciprocal gestures. This is collateral egalitarianism that is the foundation of an Indigenous ontology. Balance is a primary theme.

When Maka becomes cold, Inyan creates the sun; when she becomes too warm, the moon takes life. Maka, in turn, offers herself as the place for all life to live and grow. Correspondence is an important principle. A being is only complete when it is paired with its naturally reciprocating half, and the world, in its entirety, consists of parallel, equal powers functioning in a balanced way.

Now let us contrast that with a tale of temporal events (creation, end-times) that anchor eurochristian understandings of existence. By looking for evidence of the up-down image schema, we can start with the “higher authority” – part of the “a euro-colonial hierarchic imaginary that is clearly in charge (Tinker 69). The following is excerpted from the Jerusalem Bible.

In the beginning God created heaven and earth. Now the earth was a formless void, there was darkness over the deep, with a divine wind sweeping over the waters. God said, ‘Let there be light,’ and there was light. God saw that light was good, and God divided light from darkness. (Genesis I, 1-4)

There is a force that differentiates earth and water by using a superior, inaccessible power to put them in motion with each other. In the narrative that follows, we see a staged, sequential timeline depicting the living things that populate this world, including birds, fish, animals, and vegetation. The highlight of the sequence is the creation of the first man (Adam), the prototype of humanity, who is placed “in charge” of naming the things of the world. For this task, he is given a suitable helpmate (Genesis II, 2:21).

The human creations are hierarchically ordered – first male, then female. The two inhabit a paradise and are instructed to enjoy everything, save one: they are forbidden to eat from a tree placed in the middle of the garden, whose fruit contains a secret. There is an exchange between Eve (the female being) and a serpent (that which crawls and glides – “low” in an up-down hierarchy) (Genesis II, 3:1).

The serpent hints at the knowledge of “good” and “evil” marking the first reference to an oppositional, dichotomous force that seems to have preceded creation itself. Eve eats the fruit anyway (woman as transgressor/under/beneath), shares it with Adam, (woman as seductress/lower), – and “the eyes of both of them were opened” (Genesis II, 3:7). Their disobedience of ultimate authority (creator being), results in their expulsion from Paradise.

Take note of three principles: An oppositional dualism paired with a notion of radical disobedience that comes to be called “sin.” The second, an existential schism between the creator and his creations. The third, a combination of misogyny and anthropocentrism – in an up-down schema, female is “lower” than male, humans are “higher” than serpents, etc.

Lakoff and Johnson explain the Up-Down image schema as follows.

Being moral is being Up(right); Being Immoral is being (Down) Low. Doing evil is therefore moving from a position of uprightness to a position of immorality (being low). Hence, Doing Evil Is Falling (Down). The most famous example, of course, is the Fall from Grace.

This story and those that follow do not feature balance or equilibrium. Rather, humans are isolated and estranged from the rest of creation (the world), even as they continue to occupy a place within a descending order of importance and just below the creator/god…animals follow, and so on.

Herein lies a paradox at the heart of the eurochristian worldview. The world into which humans are thrown is accursed (Genesis 3:17), and the creator-god “exacted the penalty for its fault and the land had to vomit out its inhabitants” (Leviticus 18:25).

Their debased condition produces an existential quandary. Humans, hierarchically superior to, and in charge of all other living beings, are nevertheless alienated from all the living beings of the world. Cast out, they face an inhospitable world, and yet, the original instructions given to them are not rescinded.

Despite this estrangement, they are nevertheless still instructed to subdue, use, tame — “fill the earth and subdue it…have dominion over the fish of the sea and the birds of the sky and all the living creatures that move on earth” (Genesis 1:28). It should not surprise us, although it is ironic that President Trump recently invoked the concept “tame” to describe the colonization of this continent.

The descendants of this tradition (Huckabee Sanders, AOC, myself…anyone who shares the worldview) are obliged to carry the divine instructions. The word used to describe this responsibility today is “stewardship.”

What does any of this have to do with American political realities? With the gross distortion of events near the Lincoln Memorial in January? With climate change? In a word, everything.

Let’s return to the testy exchanges between Huckabee Sanders and AOC for a moment. Vine Deloria Jr. (Yanktonai/Sihasapa//Standing Rock Sioux), describes the effectiveness of a false binary: “Liberals,” he writes, “appear to have more sympathy for humanity, while conservatives worship corporate freedom and self-help doctrines underscoring individual responsibility” (62).

All of this is a clever fabrication, but the illusion functions impeccably well to ensure that conditions are always favorable for uninterrupted replication of eurochristian conceptual categories, embodied and acted upon to devastating effect. Basic philosophical differences between liberals (even self-described progressives) and conservatives are not fundamental, because “both find in the idea of history a thesis by which they can validate their ideas [and] the very essence of Western European identity involves the assumption that history proceeds in a linear fashion; further it assumes that at a particular point…the peoples of Western Europe became the guardians of the world” (Deloria 62, 63).

The conceptual fabrication relies on constructing what appear to be static, opposing political interests that are then imagined to be representative of radically different agendas and commitments. This is embodied metaphor, effectuating a massive distraction within dominant culture (thus making it impossible to appreciate or even recognize Indigenous ways), and it is culturally embedded to such an extent, it successfully reifies “givens” of the dominant way-of-being – thus cognitively reproducing and normativizing a radical individualism that elevates the eurochristian ontology.

Jacqueline Keeler (Diné/Ihanktonwan),remarking on the videos emerging from the event, identifies a “triumvirate of experiences that largely define American history.”

I see it as a very interesting moment, a moment where three streams of American experience all met, on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. We were all coming at this from different directions based on our own experiences that we’ve had under the system that we live under. For hundreds of years it’s been a system of white supremacy that accompanies colonialism, and so you have a group of young men who benefit from that and live in an environment where they appear to not be aware of how other groups view their privilege. And then you have a situation where the adults in their lives have not informed them of how to live in a pluralistic society.

The next steps, Keeler says, are “beginning to understand the Native American perspective to a much greater degree…the Catholic Church in particular [must] recognize its role in the harms done to Native people.” I agree, and hold responsible all who (including myself) have unconsciously (according to cognitive science), but also quite deliberately, allowed and benefitted from, the replication of eurochristian conceptual categories that not only place humans in a supreme position, but also impose stratifications within that category.

Specific conceptual metaphors that have been replicated and reified in churches, courtrooms, residential boarding schools and elsewhere, rapidly intensified due to “massive European immigration around the turn of the 20thcentury.” Michael Omi and Howard Winant identify ethnicity theory as the first mainstream social scientific account of race that understood it to be a socially constructed phenomenon. Distinguishing, then assigning racial status, coupled with systemic assignment of group identity (think Ellis Island), they write, are “practical tool[s] in the organization of human hierarchy” (22).

As ever-increasing numbers of new Europeans began to invade, it became necessary for those who had already successfully colonized, to classify them as “whites of a different color.” This both assigned a separate status for them and distinguished them as “above” “higher than” Native peoples as well as African Americans and other people of color. These separate statuses continue to be upheld in the rule-of-law – in courts, executive proclamations, legislative decisions, police encounters, and popular culture. That is how White-ness remains the dominant conceptual category.

I argue, following Ian F. Haney-Lopez, that while race has become “common sense” in courtrooms and other legal venues, “the confounding problem of race is that few people seem to know what race is” (165). That unawareness explains partly why neural activations are unnoticed by us. Yet because they are culturally-generated and rooted in shared ways-of-being, we experience marginalization and/or privilege together.

Ignorance of cognitive processes by which a worldview that posits cultural genocide as “progress” is constantly recreated via formidable metaphors, is key to its imposition and dominance. Therefore, apprehending how every social institution reifies these categories religiously, as well as how sacred notions of possessive individualism and appropriative self-interest are worshipped and honored, is critical. This system dominates and will continue to do so until the powerful cognitive processes that keep it in place are known and understood.

Wendy Felese, mother and aspiring musician, is a professor of religious studies in Denver, Colorado. She is an avid promoter of traditional environmental knowledges and is convinced that Indigenous ontologies, expressed by those with the cultural competency to do so, are an antidote to contemporary, reckless ecological destruction.