After the Great War, the Great Depression, and the Holocaust, many thinkers tried to figure out what was wrong with the world. I’ve discussed some of their work in earlier posts, especially “The Idiocracy Experiment,” but have been saving The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements for when the uprisings, which I predicted in the middle of March, began. It’s not clear these widespread agitations will coalesce into broader rebellion or civil war but in any event, The True Believer is worth considering.

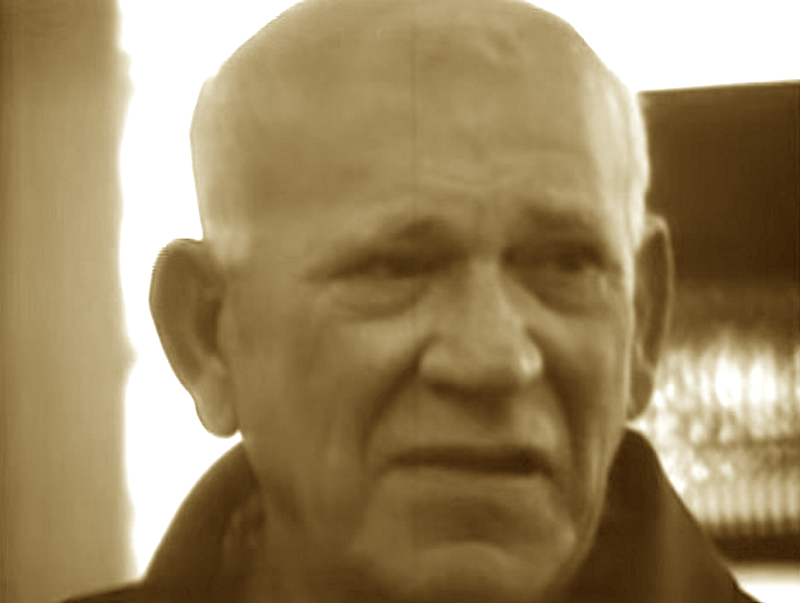

This little book, first published in 1951, made a big splash by taking an interdisciplinary look at the root causes of fascism and communism. Its author, Eric Hoffer (1898-1983), was a longshoreman and autodidact. Between unloading and loading ships and frequenting brothels, he eventually managed to write enough books to teach at Berkeley, albeit “only” as an adjunct.

Hoffer realized that the “abject poor” are too busy scraping by to cause much trouble for anyone. “Frustrated” people who thought they were going to have better lives are the ones who join rebellions and mass movements. The abject poor expect nothing and hence are not disappointed when that is what they receive. The frustrated had, or at least expected to have, a little something and when they lose it, or realize that they are not going to get it, they are susceptible to whatever ideology they happen to bump into.

That, Hoffer believed, explained the otherwise inexplicable phenomenon of Fascists becoming Communists and vice versa. “When people are ripe for a mass movement,” he argued, “they are usually ripe for any effective movement, and not solely for one with a particular doctrine or program. In pre-Hitlerian Germany it was often a tossup whether a restless youth would join the Communists or the Nazis.”

Mass movements, Hoffer noted, “do not usually rise until the prevailing order has been discredited. The discrediting is not an automatic result of the blunders and abuses of those in power, but the deliberate work of men of words with a grievance.” Articulate people with grievances abound today and they enjoy platforms as never before and many eager listeners.

Frustrated people suffuse America, making it ripe for mass movements, even ones based on incoherent or exploded ideologies like radical environmentalism, socialism, or, if I may coin a phrase, Lockdownism, the largely irrational belief that COVID-19 necessitated shutting down most of the economy.

Most importantly, many African-Americans expected big improvements stemming from improved access to the polls, the election of Barack Obama to the presidency, and better employment opportunities. Some looked forward to reparations for slavery or at least to a reduction in the ferocity of its heinous offspring, the carceral state.

But then the novel coronavirus hit and many African-Americans frustrated by the economic lockdowns, which either cost them their jobs or small businesses or, perhaps worse, saw them cajoled into assuming presumably large health risks to do “essential” jobs that paid no more than when they were considered just lowly service jobs. Then came data showing that they were dying disproportionately from COVID-19. The George Floyd video was the final straw.

Lots of other Americans are also frustrated. Their putative leaders have infantilized them through decades of paternalistic laws that try to micromanage their lives. It is beginning to dawn on them that election results are unlikely to change anything under our duopolistic, or revolving monopolistic, political system.

Leaders tell young Americans that they must graduate from university to enjoy “the good life” but many students accumulate more debt than valuable skills. Worse, many learn to hate themselves due to their gender, skin color, and/or religious beliefs and are inculcated with falsehoods about the crucial role of markets in our society.

Public schools and many universities, public and private, brainwash young people to believe that “democracy” means “voting,” as long as the vote is for a Republican or, better yet, a Democrat. Votes cast for others are simply “thrown away.” The fact that voting to change the outcome of an election is essentially irrational is not discussed. Celebrities tell people to “vote or die” and many of them do vote but, of course, never receive satisfaction, even when their Frick defeats the evil Frack. Or is Frick the evil one?

Either way, somebody wins and somebody loses and most people (those who don’t vote and those whose side loses, which combined almost always constitute a majority) remain frustrated as years turn into decades. Some turn to drugs and overdose, or kill themselves outright, or eventually succumb to diabetes or suffer other “deaths of despair.”

Others turn their desperation outward, seeking meaning in an otherwise frustrated life by telling other people how to behave. “A man is likely to mind his own business when it is worth minding,” Hoffer warned. “When it is not, he takes his mind off his own meaningless affairs by minding other people’s business.”

That intrinsic paternalism is one reason why classical liberalism does not lend itself well to mass movements. Another issue, Hoffer explained, is that “freedom aggravates at least as much as it alleviates frustration. Freedom of choice places the whole blame of failure on the shoulders of the individual.” The True Believer can believe in just about anything except him or herself.

“Mass movements can rise and spread without belief in a God,” Hoffer explained, “but never without belief in a devil. Usually the strength of a mass movement is proportionate to the vividness and tangibility of its devil.” He was speaking metaphorically of course and meant there must exist some credibly dangerous foe to combat, members of a despised race, religion, or political party perhaps. Americans today see more devils than one can count, from antifa to the KKK, One Percenters to the Deep State, and POTUS to the Speaker of the House.

The uprisings can be viewed as a search for the right devil, the one that will unite the most people with the most power because, as Hoffer explains, “common hatred unites the most heterogeneous elements. To share a common hatred, with an enemy even, is to infect him with a feeling of kinship, and thus sap his powers of resistance.”

But hope remains. The “silent majority” may well come to see the protestors as the devil to defeat and adopt sensible reforms, like the wholesale adoption of South Dakota’s constitution and laws. I kid you not. In 2015, I explained the way that South Dakota’s government and culture combined to ensure a thriving entrepreneurial political economy in Little Business on the Prairie.

Not even South Dakotans believed me then but anyone who has been paying attention will see that the state did not lock down, its economy is doing as well as it can given the negative externalities caused by the lockdown of its trading partners, its record on COVID-19 is solid, and as on Sunday night, as May turned into June, it easily repulsed an attempt to burn down its biggest city, Sioux Falls.

Don’t get me wrong, South Dakota has problems, but they pale in comparison to those in most other states. No state income taxes, Constitutional carry, high marks on economic freedom, and high scores on standardized national exams, achieved without creating a bunch of baby commies, should look pretty good to lots of Americans right about now. And precedents for copying the constitutions, statutes, and case law of other states abounds. Delaware, for example, copied New Jersey’s corporate law in toto to win the great charter mongering war in the early twentieth century.

Right now, youngsters are playing tee ball and other forms of baseball in South Dakota, where people on radio stations remind listeners of their “personal responsibility” without getting fired and if they are razzed for it, it is for stating the obvious.

Robert E. Wright is the (co)author or (co)editor of over two dozen major books, book series, and edited collections, including Financial Exclusion (2019). Robert has taught business, economics, and policy courses at Augustana University, NYU’s Stern School of Business, Temple University, the University of Virginia, and elsewhere since taking his Ph.D. in History from SUNY Buffalo in 1997. Article republished in part from AEIR as follows: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.