The following is the first of a two-part series. It continues with a theme developed in earlier articles, which can be found here and here.

If we gaze at history with a panoramic angle of vision, we must draw the inevitable conclusion that the thesis of sovereignty radiates from the dialectic of subjection and abjection. To have subjects within the matrix of a monopolitics, and to be a subject in the philosophical and psychoanalytic coinage of the phrase, are not necessarily correlated with each other.

The first carries with it certain hierophantic implications. As is the case with the well-known expression “the queen reigns but does not rule,” a monarch may be “sovereign”, especially to the degree that parliament and her “subjects” are concerned, to the extent that she in her person signifies the transcendental background to the visible state apparatus. But that is not the kind of sovereignty which Bodin analyzed.

For Bodin, the sovereign rules but does not necessarily “reign”, if by the latter we mean the power to formulate the transcendental precepts by which the laws of the land are authorized. Bodin is absolutely clear that sovereigns are not bound by their own laws. “Persons who are sovereign must not be subject in any way to the commands of someone else and must be able to give the law to subjects, and to suppress or repeal disadvantageous laws and replace them with others – which cannot be done by someone who is subject to the laws or to persons having power of command over him.”(11)

At the same time, the sovereign’s absolute power, so far as it applies to his “rule”, correlates with the indivisibility of sovereignty itself. But such sovereignty is absolutely limited as well by the transcendental conditions which make absolute sovereignty possible in the first place. Those conditions should be articulated not as the capacity for unlimited decision-making, as with any Schmittian version of “political theology”. They are inscribed within a political ontology. “But as for divine and natural laws,” Bodin writes, “every prince on earth is subject to them, and it is not in their power to contravene them unless they wish to be guilty of treason against God, and to war against Him beneath whose grandeur all the monarchs of this world should bear the yoke and bow the head in abject fear and reverence.” (13)

Broadly conceived, sovereignty as first elaborated in the early modern period, therefore, follows without exception a dialectic of subjection and abjection. The monarchial sovereign is only sovereign because his or her unconditional power of subjection depends on an unconditional abjection before the throne of God. The nexus of sovereign authority is a vertical one in accordance with which the play of “resemblances”, as Foucault describes the method of knowledge formation up until the sixteenth century, prevailed. “The universe was folded in upon itself: the earth echoing the sky, faces seeing themselves reflected in the stars, and plants holding within their stems the secrets that were of use to man.” (19).

If any meager hint of a “popular” sovereignty can be found in Bodin’s writings, it is only because the soul of the human subject itself intrareflects this transcendental pattern. Bodin remained a Catholic to his dying day, and thus has come down to us as the architect in many respects of the seventeenth century justification for absolute monarchy that propelled both the rise and fall of the ancien régime.

But John Calvin, whom Ralph Hancock has profiled as the true progenitor of modern democratic polity, expressed some of the same sentimentality in the last chapter of his Institutes of the Christian Religion when in his attack on antimonianism and his elevation of the power of the civil magistrate he declared that “spiritual freedom can perfectly well exist along with civil bondage.” (1486) Calvin’s allowance for “civil bondage” is closed tied in with his doctrine of reprobation, which in turn stems from his distinctive teaching concerning “double predestination,” i.e., the conviction that God preordains that some will be saved and others damned.

The doctrines of reprobation and double predestination were Calvin’s refinement of Augustine’s interpretation of divine providence in his arguments against Pelagius, particularly the treatise On Grace and Free Will. Although Calvinists are largely in agreement that God does not willfully consort with reprobates to foment their damnation, like Augustine they hold the view in varying degrees that He creates and disposes some who will not only stray, but actively oppose him. In the Calvinist mind set this cosmic chiaroscuro of created entities who are both serving and resisting the divine majesty attests to his absolute sovereignty as well as redounds to his “glory”.

The nuances in the idea of double predestination have become myriad and overdetermined throughout the modern era. But it is safe to say that the expression of a unitary ontology of divine singularity in a monopolitics of limitless control over the life and death of those within the boy politics is mirrored not only in the Calvinist imaginary with respect to the heavenly realm and the destiny of souls, but also in the Genevan Consistory which sought to regulate in a manner that prefigured modern totalitarian states all aspects of human behavior and to educate their children into the authorized faith. Calvinism, in other words, did not manifest the principle of indivisible sovereignty in the person of the monarch, but in the power of state apparatus which would cite as its raison d’etat the necessity of pleasing and glorifying the Deity.

In his classic study that traces the genealogy of modern radical politics to early Calvinism, Michael Walzer points out that it was the doctrines of predestination and reprobation that created a unique kind of worldy “saint”, who later became the virtuous citoyen in French revolutionary theory. “Saint and citizen together suggest a new integration of private men (or rather, of chosen groups of private men, of proven holiness and virtue) into the political order, an integration based upon a novel view of politics as a kind of conscientious and continuous labor. This is surely the most significant outcome of the Calvinist theory of worldly activity, preceding in time any infusion of religious worldliness into the economic order.”(2)

Through the compulsion of a powerful, sovereign Deity heavily impressing itself on the “bourgeois” conscience of the secular saint, the patriarchal, extended kinship system that had held up both the feudal social order completely unraveled and a new modern epoch, involving flattening of hierarchy in an epistemic as much as a political manner of procedure, took its place. “In politics as in religion the saints were oppositional men and their primary task was the destruction of traditional order.”(3).

We need, therefore, to give special attention to, if not to zero in on, the fungibility in the early modern years of sainthood and sovereignty. As Waltzer notes, the “collapse of the universal sovereignty of [Christian] empire” was rectified through the Calvinist sanctification of worldly enterprise as the condition of “citizenship” in a productive and expansive godly commonwealth. Sovereignty as saintliness through the emerging capitalist “thaumaturgy” passes from the potentate to the people.

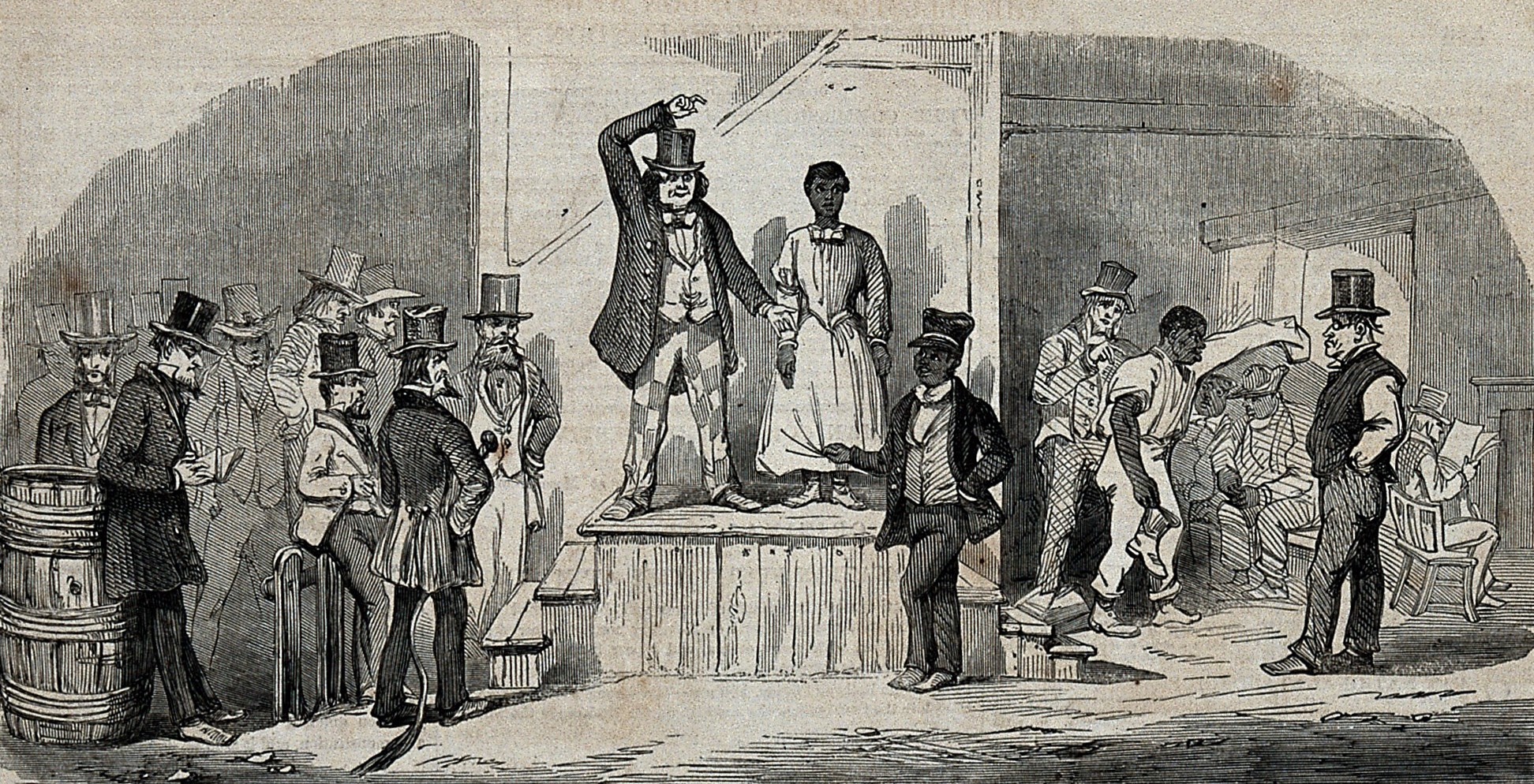

The other side of the equation of course is what the new secular mass of “reprobates” looks like exactly, and how as sainthood was gradually transformed into secular political agency. According to R. H. Tawney, who sought both to enhance as well as correct the Weber thesis regarding the relation between religion and capitalism, the tendency of late seventeenth century English Calvinism was not so much to moralize work as to glorify the amassing of riches through industry while at the same time as “to regard the poor as damned in the next world.”(501) Holiness was now transmuted into the ability to acquire property and to utilize those holdings to magnify the reach and capacity of the instruments of production themselves, leading initially through maritime and military competition with national rivals such as the Spanish and the Dutch to build trading empires and ultimately to reinvest the growing surpluses of those mercantile ventures, which included the buying and selling of course the utilization of slaves, into the capitalization of the incipient industrial order.

In Tawney’s words, “it was natural that the rigours of economic exploitation should be preached as a public duty, and, with a few exceptions, the writers of the period differed only as to the methods by which severity could most advantageously be organized.” (506). Salvation and the destitution of those who did not have the motivation, the legacy, or the day-to-day wherewithal to be ruthlessly industrious and to gain advantage over others became the operative signs of the dialectic of subjection and abjection that fostered the symbolical matrices for the early modern formulation for what came to be known as “popular sovereignty.”

As the thaumaturgy of nascent capitalism filled out, often with monstrous repercussions, made this new definition of sovereignty both pliable and plausible within the political arena, the discovery of distant lands, the encounter with strange peoples, and the expansion of world markets ensured that the same brutal theodicy first articulated by the divines of Protestant Geneva would inexorably mean the marking of these unfamiliar terrains and ill-delineated geographies with the signs of election and reprobation.

With respect to the emerging political economy, we might re-calibration the meaning of divine election as appropriation and reprobation in the guise of a strategic reclassification of cultural difference, or passivity as natural servitude, and in many cases, as slave labor. We have in the seventeenth century the first inklings of what Achille Mbembe has designated as a necropolitics that inscribes an absolute difference between sovereignty and bare life in a much earlier, broader, and pervasive manner than the paradigm Agamben, for example, has confined to the declaration of the “state of exception”, or to the concentration camp.

What is fascinating about Mbembe’s analysis of sovereignty is that he designates racism not as the metapolitical correlate to some fraught ahistorical polemical construct as the currently fashionable and presumably self-authorizing meme of “whiteness”, but as the indelible marker of colonial epistemology itself. It rides inexorably on what Walter Mignolo terms the “colonial difference.” It belongs to the calculus of sovereignty under colonial domination.

“Exercising sovereignty,” Mbembe writes, “is about society’s capacity for self-creation with recourse to institutions inspired by specific social and imaginary significations.” (68) Following Foucault, Mbembe characterizes it outside the frame of monopolitics as a form of “biopower”, which grants to the state the power of life and death. For biopower “appears to function by dividing people into those who must live and those who must die.” (71). Racism, slavery, and coloniality, as most critical contemporary historians concur, comprise an indissoluble matrix for the development of both the forces of production and the ideological superstructure that warrants it in the early modern era. As the renowned postcolonial political luminary and black historian Eric Williams has argued in his classic work Capitalism and Slavery, the explosion of the African slave trade in the seventeenth century was due largely to the decimation of the indigenous peoples of the America by disease and deliberate policies of extermination, especially in the Caribbean.

At the same time, the emerging mercantile system of trade and finance in Europe required industrial scale production of agricultural commodities in the newfound lands, which only the systematization of chattel slavery could sustain. “With the limited population of Europe in the sixteenth century, the free laborers necessary to cultivate the staple crops of sugar, tobacco and cotton in the New World could not have been supplied in quantities adequate to permit large-scale production. Slavery was necessary for this, and to get slaves the Europeans turned first to the aborigines and then to Africa.”(6).

But this new and far-reaching manufactory of export wealth requiring the mass commodification of labor inputs along with the brutalization and dehumanization of the laborers themselves could not have been kept intact for very long among peoples with a presumably “Christian” conscience without a transformation in the standard anthropology of human differences. As it turned out, the enormous value-added proposition behind the industrial system of slavery, and its outsize role in fostering the economic advantages accruing to the rising modern nation-state, was offset as well by the ever present danger of slave rebellions.(223).

It is in this context that Mbembe’s necropolitics as the quest for sovereignty based on the mechanized devaluation of human life, both material and symbolic, in the pattern of the later concentration camp triumphed. Mbmembe writes: “the perception of the existence of the Other as an attempt on my life, as a mortal threat or absolute danger whose biophysical elimination would strengthen my life potential and security—this is, I maintain, one of the many imaginary dimensions characteristic of sovereignty in both early and late modernity.”(72)

The “mortal threat” of the slave was not only to the life of the immediate master. It was to the fast-expanding system of extractionist mercantilism that stoked the engines of economic and population growth as well as the new appareil (as Foucault would call it) of scientific and technological “progress”. Calvinist theology played a crucial part in incising with regard to the authorization of cognitive frameworks, at least in Protestant countries, the sharp differential between those who thrived and those who merely survived, or who were terribly exploited for the glory of both God and the national treasury. But the vast, international, secular regimen of worldly salvation and reprobation accrued from the experience of a jarring alterity that dominated the minds of Europeans confronted with both resistant indigenous nations and the squalid contagion of industrialized chattel slavery.

It was also the alterity of radical subalternity that made skin color for the first time in European perceptual codes into a signature of abjection. According to Mignolo, the markers had been forged in the Medieval effort to articulate in a more “natural” idiom to distinguish between Jews, Muslims, and Christians as one of “blood”. The religious differend recognized a certain ethnic genealogy behind it, often in the sense of the identification of Christians as inhabitants of the Levant and westward. But it was rather vague and diffuse.

It is noteworthy that Medieval and Renaissance thinkers did not have anything remotely approximating the current concept, even when dealing with darker Middle Easterners or Asians, of “people of color”. By the time of the European Enlightenment, however, “‘blood as a marker of race/racism,” Mignolo writes, “was transferred to skin. And theology was displaced by secular philosophy and sciences.” Furthermore, the rage for taxonomy that characterized the eighteenth century reinforced this trend. “The Linnaean system of classification helped the cause.” (9).

Thus the sovereignty of embodied sovereigns passed over into the modern sovereignty of capital through this radical repositioning of epistemic boundary signs as part of the “secularization” process itself which, in turn, rested on the utopian project of what Descartes and Leibniz had termed a mathesis universalis, a “universal science” that transformed the cognitive order from a fluid, slippery, metonymical mess of revered ancient ideas, religious dogmas, and folk beliefs and superstitions drawn from a farrago of tribal histories into what Boaventura de Sousa Santos has dubbed a “cognitive empire” that minced the world into atomized and abstract heurisms, fostering a new all-encompassing “progressive” system as well as an unassailable ideology justifying the domination, exploitation, and in many instances extermination of certain marked bodies for the sake of a self-replicating and self-aggrandizing productivist economy.

Carl Raschke is Professor of Philosophy of Religion at the University of Denver, specializing in Continental philosophy, art theory, the philosophy of religion and the theory of religion. He is an internationally known writer and academic, who has authored numerous books and hundreds of articles on topics ranging from postmodernism to popular religion and culture to technology and society. Recent books include Postmodern Theology: A Biopic(Cascade Books, 2017), Critical Theology: An Agenda for an Age of Global Crisis(IVP Academic, 2016), Force of God: Political Theology and the Crisis of Liberal Democracy (Columbia University Press, 2015) and The Revolution in Religious Theory: Toward a Semiotics of the Event (University of Virginia Press, 2012). His newest book is entitled Neoliberalism and Political Theology: From Kant to Identity Politics, (Edinburgh University Press, 2019). He is also Senior Consulting Editor for The New Polis.