A variety of competing descriptions of ‘whiteness’ making up racist retreats to Romantic imaginaries of Anglo-Saxon identity go at least as far back as Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson had imagined himself in an anti-papal tradition of resisting “the Norman yoke,” installed in with the papal backing of the French invasion of England in 1066, and the excommunication of King Harold (Williams 31). To me, it seems timely to critically look at the political-theological impulses toward “Anglo-Saxonist” claims.

In his exhaustive history of the legal concept of ‘Discovery’ as it was imported from European international law into the United States’ legal system, Robert J. Miller traces Jefferson’s early work as a lawyer on Indian land claim disputes, his outlining of Cherokee removal as Secretary of State in the 1790s, and his aspirations to Empire in the Louisiana Purchase. Miller corrects some historical conceptions, noting that the purchase was not a “real estate” deal (71).

It was a transfer of the rights to Discovery, which inherited a long history of rhetorics of “just war” to remove Indigenous people from land and transform that land from a “right of preemption” into property. A declaration of a “just war” could expedite this process (64).

But whether it is Thomas Jefferson or Jefferson Sessions, whose Wikipedia editors find it importantly relevant to cite that both of his parents come from primarily English and some Scots-Irish blood – such imaginaries prevail today, in archaic notions of “blood” that carry on legacies of deeper forms of enculturation.

Long before the last election, psychological surveys showed correspondences between rising fears of racial persecution among whites and declining senses of discrimination among non-whites, and sociological studies have long shown the current Attorney General’s support for regional laws steeped in a history of ballot manipulation. But it was Sessions’ invocation of Saint Paul to justify harsh immigration policies this summer that most clearly displayed his Anglo-Christian political theology.

How does such rhetoric work? The constructed genealogies of those narratives affect the lives of others when embraced by powerful public figures, whether or not they are true. Such intergenerational identity formations run deeper than an inquisitive glance at ancestry.com or 23andme.com. They draw on what George Lakoff has called, “deep frames.”

In The American Indian in Western Legal Thought, Robert A. Williams Jr. traces the Romantic thought expressed in Jefferson to late medieval papal bulls and legal thought. He writes:

In constructing their discourses of resistance to British power in America, radical colonists appropriated themes and concepts from an eclectic array of sources. The Enlightenment-era discourses of natural law and rights; the British Constitution; the mythology of a purer Saxon-inspired legal and political order in the New World freed from the yoke of Norman-derived feudal tyranny; and especially the common-sense view of property as acquired by labor and governments as established to protect property found in the texts of John Locke – these are the most frequently raided discursive formations. (228-229)

I have written a lot recently on The New Polis regarding Indigenous issues. This is due to an ongoing critical inquiry into the ways “the old polis” was structured in relation to “barbarian” others as far back as Aristotle’s Politics. Anthony Pagden’s The Fall of Natural Man excellently explores the Scholastic’s adaptation of Aristotle to faculty psychology to describe Indians’ “natural slave” mentality and the Salamanca School’s attempts to reconcile such thinking with burgeoning humanism.

My intention has been that anything we call a “new polis” cannot merely be a reaction-formation to current political and economic shifts, nor can it rely on hoary accounts of “othering,” explicit or implicit. In a sense, my approach is rather Levinasian, seeing the formation of politics within the totality of war, as expressed in the preface to Totality and Infinity.

But I am not going to rehearse a reading of Levinas here. Instead, I push toward a critique of Anglo-Saxon imaginaries by returning to an Anglo-Saxon version of a medieval history of the world produced by the student of Augustine and Jerome, Paulus Orosius.

Orosius’s history was written during the time Rome was sacked by the Visigoths (or “west”-goths), who had already been Christianized through Bishop Ulphilas’s translation of the Bible into High German. The relatively peaceful sacking of Rome by the Christian King Alaric produced nostalgia among Romans for pre-Christian periods of “peace.” Romans who felt invaded by the Visigoths blamed Christianity for the fall of Rome. Such early “traditionalist” sentiment provoked Augustine’s defense of Christianity in City of God. Orosius’s History was written as a compendium to Augustine’s massive work and was dedicated to him upon completion in about 416 C.E.

As an interesting addition to Orosius’s Compendious History of the World, England’s King Alfred (King of Wessex 871-899) had translated into Anglo-Saxon “The Voyages of Ohthere and Wulfstan.” These travel narratives mark not only the burgeoning of Anglo-Saxon cultural identity, they also mark a “transnational” (to use an anachronism) conception of history and anthropological interest in customs of various societies.

Despite his reputation as a “most learned man,” Alfred himself did not translate The History of the World (Frantzen 7-10), the editorial decisions in the work’s Old English translation display a rhetorical arrangement that reveals a particularly Anglo-Saxon ethnocentrism. Alfred heavily edited and expanded upon the popular Latin text, producing an equally popular Anglo-Saxon history widely read into early modernity.

So it is not completely accurate to refer to “Alfred’s translation,” yet the Anglo-Saxon Compendious History does display an early kind of nationalism traditionally associated with myths about Alfred, who appears to be rhetorically re-locating the center of the world from Rome to England by inserting a world geography into the first chapter. When combined with the spatial imaginary present in the text, these nationalist myths become more elucidated – and the voyages reveal more literary qualities than have been discussed.

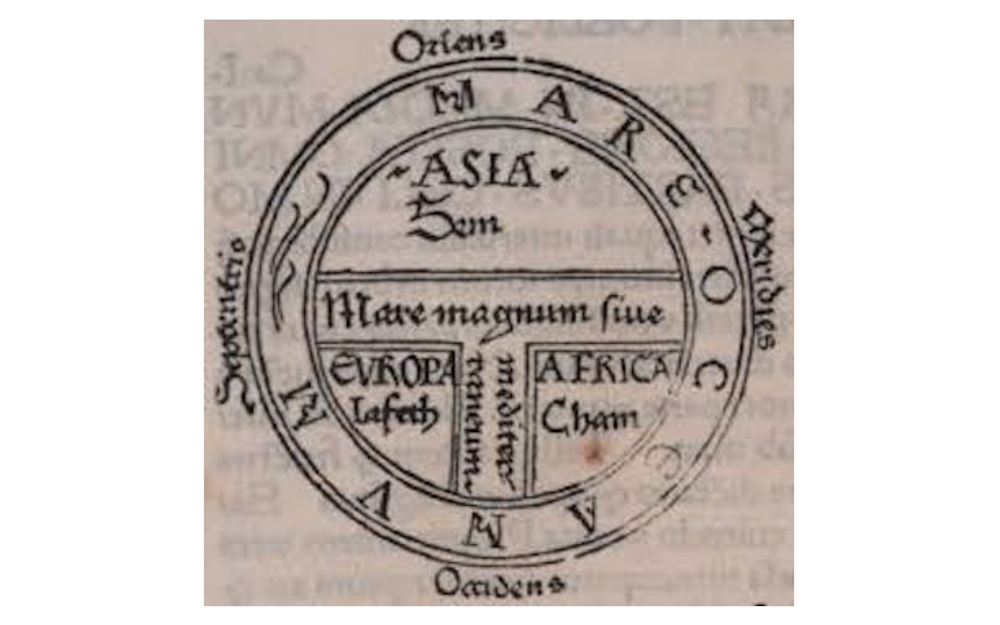

It is especially important to note this geographical addition in relation to brilliant accounts of early modernity such as Stephen Greenblatt’s study of representation in Marvelous Possessions: The Wonder of the New World, which includes what he refers to as one of the first maps, a Jerusalem-centered Beatus Map (see image above). Greenblatt points out at the end of his book the “silence of the masses” as opposed to the literate elite of early modernity, but any Anglo-Saxon scholar will be aware of the hallowed and mythological place that the metonym “Alfred” had in England because of his famous zeal for education, an attempt clearly employed in his editorial decisions for his edition of the History.

According to Joseph Bosworth in his 1852 Literal Translation of King Alfred’s Anglo-Saxon Version of Orosius’s Compendious History, the book is Alfred’s attempt to “fill the chasm” between Orosius and himself and it is “the only geography of Europe, written by a contemporary, and giving the position of the Germanic nations, so early as the ninth century” (16). Bosworth tends to read Alfred as the actual author, reading for example the “plural first person in Wulfstan” as Alfred’s own “royal we,” but I will note some differences based on a more recent reading that assumes Alfred himself is not a sole “author.”

In “Alfred’s” translation, the voyages are placed in the first chapter of the book, which begins with an account of how ancestors “divided the world” into Asia, Europe, and Africa. Geographical regions establish the conception of the world, yet one reading today still feels the Roman center of this description. Alfred follows this with a description of his reign before the addition of Ohthere and Wulfstan’s voyages. Alfred’s history, therefore, does not proceed chronologically according to the received “history of the world.” It first establishes “Alfred’s” England.

Book Two then traces the origins of Rome in a way that precedes Machiavelli’s later discourse on Livy (1531). The layout of the text moves the center of the cosmopolitan world to England. In establishing England as the center in Chapter I, Alfred proceeds by describing the (scholarly) known world, beginning with an account of Germany, then north to Scandanavia, then south to continental Europe.

While geographic region structures the layout of the chapter, knowledge of specific regions becomes more detailed in Ohthere’s narrative. The descriptions are also markedly anthropological. Wulfstan also gives accounts of peoples and various customs, with particular attention to funeral customs. Why does “Alfred” think this information is deemed worthy enough to include as an addition to Orosius’s history of the world, especially as an opening frame?

I believe that, as characters added to the History of the World, Ohthere and Wulfstan receive certain elevation in status. They mark a kind of ascendancy to what we would later call “middle-class” status but what the medieval English world called a “thane,” who had crossed the channel multiple times to trade successfully. As Fabienne Michelet argues, “the two travellers’ accounts present [England] as an attractive centre of power and culture, as a place where the explorers find an audience and where the information they gathered in the course of their expeditions will be preserved” (26).

On a literary level, scholars have also noted that “The Voyages of Ohthere and Wulfstan” give us an account of a more prosaic, and less poetic, style of writing that may have been closer to the Anglo-Saxons spoke in everyday life than the episodic poetry of the period. We should think of this again with respect to Stephen Greenblatt’s thesis in Marvelous Possessions concerning the importance of subservient and “lower class” voices appearing in the literary texts of their social “superiors.”

In other words, Alfred’s political-theological agenda – for both Orosius’s and Alfred’s devout Christianities underwrite the History — reads to me as an attempt to have important texts translated into Anglo-Saxon as a way of increasing effective governance. A certain linguistic status is then given to the voyages because the were transliterated into Anglo-Saxon, giving the prosaic and “non-fictional” accounts a kind of linguistic privilege over heroic poetry. To see what I am getting at, one needs to be attentive to the layer of “heroic deeds” at work in the subtext of the voyages.

Ohthere’s accounts are written in the third person, in a kind of journalistic manner. The scribe often gives specific attention to what “Othere said,” creating a certain narrative distance. Still, the authority rests with Ohthere, not the scribe. With him we see an example of the “true thane,” who has had many travels away from the coasts of England.

Jonathan Slocum identifies Ohthere as “a Norwegian hunter, whaler, and trader who tells among other things of his voyages north and east of the Scandinavian peninsula, round the Kola peninsula to the White Sea (all of these terms being modern).” But Ohthere’s status of having lived “farthest north” is also given in the text.

In line six the scribe writes: “He saede þaet æt sumum cirre wolde fandian hu long þaet land on norþryte læge, oþþe hwæðer ænig man be norþan ðæm westenne bude” (He said that, at a certain time, he would find out how long that land in the north lay, or whether any man abode north of the waste). He later sails further east into the White Sea, where he encounters Finns and Biarmian’s.

Toward the end of the passage, in line eighty-one, the information is repeated: “He cwæð þæt ænig nan man ne bude be norðan him” (He said that no man abided north of him — Halgoland, Norway). I take this partly to mean that Ohthere is not just that he is a trader or a whaler. Ohthere’s status with respect to this revised history seems to be partially based on his being an adventurer, but also that he is rich in tributes.

That he was a kind of extremist, but also that he was to in a way claim the northern wastes for the known English world. I also believe that such an extremist element elevates his otherwise prosaic recounting to a kind of literary status because of the geopolitical information his narrative contributes to the revised history of the world.

Surely, the History is presented as non-fiction, but the modern distinction between history and myth is not very applicable. The extremism invokes heroic sensibilities valued in the Anglo-Saxon culture. The information is also privileged because Rome did not have it.

It makes sense that Alfred would want to know as much as he could about the places and peoples with whom the Anglo-Saxons could have commerce. The larger passage has a kind of meticulous detail that is astonishing to consider when one thinks of the time it must have taken to write down an oral account. The very fact it was recorded alerts to us that the information was rather serious business.

In 21stcentury terms, the information may well be tactical in terms of both commerce and “national security.” E.D. Laborde has noted that the voyages are an especially important addition to Orosius’s history because of their accuracy and because “the voyages of Ohthere and Wulfstan are the earliest accounts in our language of the voyages of discovery, and [they] indicate the methods employed by the great king in collecting the information of foreign lands” (133).

What seems rather remarkable, however, is the inclusion of the passage in the revised Compendious History, especially if it was only for this rather strategical purpose. Thus, I believe that, as part of the History, we are witnessing here an elevation of the status of the travel narrative to the literary / historical frame, what William Cavanaugh has articulated recently as the mythological foundations of politics.

As “characters” then, in Alfred’s history, Ohthere and Wulfstan are elevated. While scholars naturally tend to focus on the historical accuracy of the detail in texts, it is also worth considering how the attention to anthropological material in the voyages evidences a perspective that values details relating to class and custom, an early example Said’s Orientalism.

This perspective, when compared with other literary material, helps us understand the overlap between “literary” and “non-literary” inclusions of within the history – frames which necessarily arose later. Anglo-Saxon works, both in language and in content, provide clues as to the editorial rhetoric behind the Anglo-Saxon version of The History.

Let me be more specific. Wulfstan’s voyage celebrates the “Eastern lands.” Unlike Ohthere’s passage, only the first two sentences are in the third person. The third sentence shifts to the first person. Wulfstan / the scribe says: “and thonne Burgenda land wæs us un bærbord.” There is in my reading a different level of intimacy between the writer of the Wulfstan passage and the content of its text than there is between the writer of Ohthere passage and the text.

That the two passages likely have different “authors” is not remarkable outside of traditional tendencies to assign authorship to Alfred. But the attention to what Othere says seems to give him more of a “special,” possibly heroic status. Particularly striking with the Wulfstan passage, on the other hand, is the amount of detail Wulfstan gives to customs and funeral practices in the Baltic.

He says, “þæt Estland is swyðe mycel, and þær bið swyðe manig burh, and and ælcere byrig cyning. And þær bið swyðe mycel hunig, and fiscað, and se cyning and þa ricostan men drincað myran meolc, and þa unspedigan and þa þeowan drincaþ medo” (And there is so much honey, and fish, and this king and those rich men drink mare’s milk, and the unwealthy and the servants / slaves dink mead). This passage reveals not only the abundance of lands but an existing division between social classes according to drink.

Class and rank also appear to be of concern to Wulfstan when he describes funeral horse races and the redistribution of a dead man’s wealth. According to Wulfstan, mourning periods for someone echoed the importance and wealth he had in a community. Wulfstan says the “unforbærned” body of a rich man could lay above ground for up to six months after death.

In “Wulstan’s Voyage and Freezing,” A. Macdonald cites Sir Aurel Stein’s study, Ancient Khotan, which discusses how keeping a body cool enough not to spoil, “sam hit sumor sam winter” (whether its summer or winter). Stein’s study discusses ancient refrigeration practices in certain parts of eastern Europe still present in the early twentieth century in which an ice pit was dug and covered with leaves. Macdonald speculates that Wulstan was probably unaware of the ice beneath the corpse (73).

Along with presevation practices, Wulfstan remarks on funeral games, where a dead man’s property was divided into sections according to value and then distributed as prizes to the man with the fastest horse. The value of the horse is revealed here as necessary for participation in the accumulation of wealth, and the practice also shows an emphasis on skill and ability rather than inheritance.

The cultural practice shows a society favoring physically skilled men competing through strength, so commerce alone did not preserve a community. Wealth was redistributed among those most capable of providing military protection to the community. As with what I have read as the heroic nature of Ohthere’s status, Wulstan’s description of the winner displays the valuing of “heroic deeds.” This emphasis becomes importantly evident when we consider Alfred’s legal codes, because they blend such practices with the Judaeo-Christian / patriarchal conceptions with inheritance by lineage.

Allen J. Frantzen has pointed out that in Alfred’s introduction to the Law Codes, he takes pains to situate them within biblical tradition (14-15). It would not appear logical to for Wulfstan’s passage to be included in the History were it to merely celebrate pagan funeral practices that contradicted Anglo-Saxon law and Christian practices. This leads me to believe the anthropological material served another purpose — one that was culturally appealing because of the emphasis on heroism.

Scholars have more recently attempted to destabilize the mythological status attributed to Alfred over the centuries, claiming he added little to existing laws. In “The West Saxon Inheritance,” Nicholas Brooks argues:

We find no truth in the medieval myth that [Alfred] invented the hundred tithings of England; nor did he give any new shape to the West Saxon shires; nor, it would seem, to the ancient hidage assessment that formed the basis of public obligations. his achievement lay rather in getting more service out of his nobles and out of the ceorls on the warland than his predecessors had managed, in getting boroughs not only built but also garrisoned, and thereby in making the first tentative steps toward an urban future. (173)

These achievements are still in line with Alfred’s comments on the state of learning in England and his pains in the introduction to the Law Codes to situate England as a Christian nation. In light of this, Wulftan’s observations seem particularly notable because burial practices were quite different for Christian Anglo-Saxons.

Even for pagan Anglo-Saxons, an important person (or in some cases persons) was buried above ground in a mound. While the absence of bodies in many of these mounds may suggest that the physical remains were burnt, many mounds have, as Hilda R. Ellis Davidson catalogs in “The Hill of the Dragon: Anglo-Saxon Burial Mounds and Archaeology,” contained the treasure and personal items belonging to the dead person. She suggests that “the most likely explanation seems to be that the bodies of the king and queen were removed to give them a christian burial” (172).

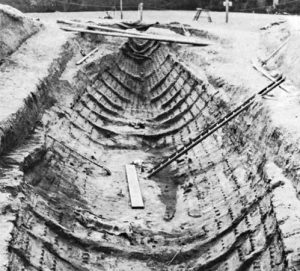

While dead men in Wulfstan’s descriptions are eventually burned with their weapons, Davidson’s study discusses undisturbed graves both with household items such as bowls and sometimes extravagant items such as ships. She claims “In these tombs men (and at Osberg a woman) were buried with rich possessions, usually with sacrificed animals and possibly human beings also, in sea-going vessels or smaller boats. Ship-funeral was regarded as predominantly Scandinavian, yet the Sutton Hoo grave [see image below], dated about 650, is as early as any dateable.”

The shift from ship-burials, originally at sea, to mound burials and eventually away from cremation, accompanies the shift from pagan to Christian ritual practices (174). Moreover, it was believed that evil spirits and dragons, as in Beowulf and, more popularly depicted in Tolkein’s Anglo-Saxon-influenced novels, guarded the mounds from grave robbers. Concerning the end of Beowulf, Davidson writes:

Besides the usual ritual at the death of a king and hero, the burning of arms and treasures on the pyre with him, there is a new factor, since the Geats decide to sacrifice the great treasure he has won from the dragon and commit it again untouched to the earth from which it came. They were wise in this, for we are told that a curse had been laid on it. (183)

Wulfstan’s observations of funeral practices on the continent are more radical when compared to this context. Wulfstan notices the redistribution of an important man’s wealth, rather than a sacrifice of that wealth. Although the funeral games still evidenced a kind of hero worship the social practices are more civic. Alfred’s task was certainly a Christianizing one, yet his conservative approach to maintaining the laws of his Anglo-Saxon ancestors displays a cultural homage and reverence for the pagan Geats. Along with his Christian agenda, it is important to trace the lineage of the Saxons here back to the continent and to the Germanic heroic code.

While the voyages remain notable for their more mundane language, they reveal cultural aspects conveyed in what we would call “literary” material today. Davidson argues for archaeological evidence’s potential to shed light on the poetry of the period. If one compares the non-fictional voyages with poeticized accounts such as “The Battle of Maldon,” one sees a clear amplification of the heroic code.

Dorothy Whitelock claims the poem “proves that the ancient Germanic code was not dead” in the actual battle, which occurred in 991 C.E. (116). Since Kemp Malone has dated Ohthere’s voyages to before the 870s and noted little disagreement among scholars that Alfred’s literary period was probably during the 880s, this puts the voyages well within the heroic period, allowing comparison of the themes and language with the poetic account of the “Battle of Maldon” a century later (80).

Interestingly, if Malone is correct in dating the voyages before 870 C.E. then they actually occurred before Alfred became king, making the editorial decision to include them more striking. It is worth considering that the inclusion of the voyages was at least partly due to the cultural prevalent of the heroic code. They had a kind of “literary” value while also marking a shift toward document-centered and prose-based society.

Anglo-Saxon poetic amplification occurs with the repeatedly episodic accumulation of descriptive clauses, often unified by alliteration, which holds the audience’s attention by focusing on a particular image. In “The Battle of Maldon,” for example, the hero, Ealdorman Byrhtnoth, is introduced: “Ða thær ongan beornas trymian, / rad and raedde, rincum tæhte, / hu hi sceoldan standan, and ne forhtedon na” (That there Byrhtnoth strengthened his warriors / riding and ruling, taught them / how his shield stands, / and doesn’t fear anything) (lines 17-19).

How often we see this galvanizing rhetoric in television and film today! In the voyages, and particularly in Wulfstan, clauses tend to be joined either by the coordinating conjunction “and” or the subordination “þa.” These connectors begin to give a more fluid rhythmic feel to the prose lessening the episodic nature of the poetry. In the poetry, frequent caesuras leave pregnant pauses, requiring the listener to fill in the gaps and stay attentive to the story. But heroic content remains prized.

Recent scholarly work, in addition to giving lie to ancient myths about King Alfred, have noted that Enlightenment scholarship imposed ideas of nation states onto their examinations of medieval governance. This perspective results in ideas of Alfred (or later Jefferson or Washington) as a “founder” of English governance, Alfred the stabilizer of older English traditions. Perhaps accurate enough for Alfred the man, but the tendency to elevate historical narrative to myth also displays a culturally binding force, a force organic to community.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, as Hugh Magennis notes in a review of Michelet’s Creation, Migration, and Conquest:

Simplifies the history of pre- and early Anglo-Saxon Britain, but contrasts with Bede’s treatment in that it draws attention to the violence of Anglo-Saxon conquest, which comes across as a brutal process. The Chronicle stresses Anglo-Saxon power and presents the Britons as a shadowy people who are defined as the enemy, deprived of history and identity. (184)

When read alongside the voyages, and particularly Wulfstan here, the Chronicle and the Compendious History validate northeastern European, Danish, and Germanic geographies and customs while drawing an identity distinctions with Britons, who were a more prevalent military threat well before the 1066 French invasion. In any case, the inclusion of the voyages establishes both ethnic and pre-Christian lineages for Anglo-Saxons.

This view resonates with Stephen J. Harris’s findings in “The Alfredian ‘World History’ and Anglo-Saxon Identity.” Harris proposes that the idea of Christendom fuels “a religion-ethnic order altogether distinct from Christianity” (482). Harris notes that Alfred’s historical conception both builds from and differs from Bede’s:

Whereas Bede appears to have maintained an almost exclusively Anglian view of ethnic identity, an identity extended to Saxons and Goths only in its religious aspect […] Alfred seems to see one common identity as extending ethnically and religiously to all Christian Germanic inhabitants of Britain. (483)

Perhaps inadvertently then, Alfred’s translation of Orosius carries on the Augustinian political-theological rhetoric in its conception of history. Harris notes that Augustine asked Orosius to compose the Compendius History in order to function, like De Civitate Dei, as a version of history’s moral lessons. However, he also notes that in Alfred’s translation, “the passages extolling the centrality of Rome to God’s plan are excised entirely.”

Thus, the idea of Christendom, if Harris is correct, underwrites in Alfred’s version of the History a kind of geographical and eventually psychological khora. This abstracted, faculty-psychological sense is what Pagden describes as present in the minds of scholars of the early modern Thomist and School of Salamanca debates a few centuries later. And Christendom remains an invisible identity construct today.

Such a current conception of Christendom, of the “Christian civilization” that much conservative rhetoric laments as cultural decay should not be distinguished too separately from these early ethno-Christian formulations in England. Nor should so-called secularists or atheists be regarded as very far from Christendom, despite a story in The Atlantic this week about how non-religiously-affiliated Democratics are “replacing” Christianity with a religion of politics.

Such a “secular” religion in my reading of deeper frames in no way replaces encultured ethnographic-Christian frames since, as Lakoff’s work among others shows, it is not a matter of rejecting a frame. Rejecting a deep frame merely reinforces that frame, which both avowedly Christian liberals and “civic” or “secular” liberals continue to do as they claim a moral superiority, conveniently ignoring how much they benefit from the rise of far right politics.

Such thinking invokes Christian salvation eschatology and the gospel of “hope.” As Christian ethicist, Miguel De La Torre writes in Embracing Hopelessness, his powerful critique of Jürgen Moltmann:

The eschatological utopia of white theologians is death-dealing to all who live in the shadow of salvation history, where justice-based praxis is either absent or refashioned as a second act to Eurocentric universal theological concepts. For the world’s disenfranchised to embrace a theology of hope, constructed independently of their real-life experiences, requires that they first deny their existential reality in exchange for the illusion of some dialectical movement toward a predominantly white utopia that continues to exclude them in the here and now.

I would extend De La Torre’s critique of Moltmann to Johann Baptiste Metz and the conception of a “new political theology” as opposed to the “old” one of Carl Schmitt’s.

My Osage friend and former professor, Tink Tinker, closely associates conceptions of “whiteness” and “euro-christianity,” which he always writes in lower case to signal the historical oppression of non-christian and especially Indigenous Peoples, long considered in the tradition I have explored here as “outside” the polis. As often happens for Indigenous People who claim ways of being outside of Christendom, pedantic charges of essentialism are thrown at them. This is merely a move to keep the power of rhetorical framing and defining within Euro-Christian rhetoric.

Attorney General Jeff Sessions continues to actively align this ethno-religious political theology in law enforcement. As CNN quoted him earlier this year:

“I want to thank every sheriff in America. Since our founding, the independently elected sheriff has been the people’s protector, who keeps law enforcement close to and accountable to people through the elected process,” Sessions said in remarks at the National Sheriffs Association winter meeting, adding, “The office of sheriff is a critical part of the Anglo-American heritage of law enforcement.”

This is the deep framing of Christendom at work, not merely the words of an ethically challenged Attorney General.

And this is not to say that there are not Christianities that are not “Euro.” As Harris’s distinction between Bede and Alfred above suggests, the binding of Christianity as a political theological project in England changed Christianity itself in ways that would later inform the anti-papal sentiments that were imported into the United States. Christians “by faith,” already inflected with the schismatic tendencies of modern identity affirmations, ought to look outside Euro-Christian framing of Christendom if they want to “salvage” something “theological” outside of aspirations to empire, but that is certainly not my project and not what I think good political-theological analyses are for.

What I have tried to point out in my analysis here is a way of locating what scholars like Tink Tinker mean when they say “euro-christian” or “white.” These are not merely the categories of neoliberal identity politics or market-constructed forms of commodity-identities.

What I am describing as the deep frames of Anglo-Saxon Christendom are wrongly interpreted by conservative Christians when they assert persecution rhetorics such as “Christians are being discriminated against!” or “Our values are being undermined.” Neoliberalism is but a an instrumentalized display of Christendom[ination]. Such persecution rhetorics merely show little faith and short-sightedness with respect to historical narratives of all kinds.

Attention to deep frames tells a more persistent story of how these claims are masks that allow people to avoid what Emmanuel Levinas calls an ethical “responsibility to the Other.” They are an atheistic denial of a metaphysical other outside the totality of war and the identities formed as reactions, as ressentiment in the totalized space.

The Voyages of Ohthere and Wulstan were likely included in Alfred’s version of The History of the World for strategic purposes, not merely tactical accounts of geography, but because the anthropological and sociological accounts in them supported an ethnic and cultural identity existing at the time alongside the religious conceptions. The Germanic heroic code provided both historical and literary elevation to Ohthere and Wulfstan’s accounts that helped maintain an ethnically grounded historical narrative.

Religious conceptions of identity transferred from Roman works show their malleability here, and when combined with ethnic history they produce a sense of citizenship loosely bound to geographical space. The “great contribution” sustained in English law appears to be the Judaeo-Christian conception of a patriarchal transfer of property, where the cursed treasures are no longer buried with dragons but accumulated through familial descent and “heritage.”

When combined with developing market-oriented culture, it seems that funeral practices where an individual’s wealth was transferred to offspring (instead of being guarded by malicious spirits) allowed for material wealth to form a new economy. While the heroic culture remains evident today, as well as in the funeral games Wulfstan witnessed, there was during the period a general shift toward a transfer of resources that function competitively among individuals.

Whether it be conceived of in terms of community wealth or Harris’s “Christendom,” it seems that the shift toward a market economy expressed by Alfred’s inclusion of the voyages allows us to see botha linguistically “practical” shift away from deed-based, episodic poetry to a collective and anonymous prose we might think of as what Agamben and Foucault call an “apparatus.” Along with the creation of liberal subjectivity and nationalist narratives of the “freedom” of that subject persist the older mythological narratives.

To speculate on the editorial reasons for including Wulfstan and Ohthere’s voyages in Alfred’s History not only gives lie to the culturally constructed myths about Alfred himself. It allows us to speculate on the limits of subjectivity and the elevation of narratives to myths that stabilize collective identities beyond geographical territory.

And that is the scary thing about the times in which we live, not that we ought to act this way or that, identify this way or that, but that an older, more hideous form of collective and indiscriminate violence drives our actions and feeds them. Perhaps this is the cursed dragon unleashed from Anglo-Saxon tombs by the embrace of Christendom as it was developing at the outset of its second genocidal millennium.

And so again, I am thinking of Emmanuel Levinas’s preface to Totality and Infinity, and the concern with whether or not we are “duped by morality.” I end with his words:

The visage of being that shows itself in war is fixed in the concept of totality, which dominates Western philosophy. Individuals are reduced to being bearers of the forces that command them unbeknown to themselves. The meaning of individuals (invisible outside of this totality) is derived from the totality. The unicity of each present is increasingly sacrificed to a future appealed to to bring forth its objective meaning. For the ultimate meaning alone counts; the last act along changes beings into themselves. They are what they will already appear to be in the already plastic forms of the epic. (21-22)

Roger K. Green is a lecturer in English at The Metropolitan State University of Denver. He is the author of Enchanted Citizens: A Transatlantic Political Theology of Psychedelic Aesthetics (currently out for peer review) and numerous short articles in Political Theology Today. He is general editor of The New Polis, where he writes monthly articles related to concerns that have come out of political theology. He is currently ABD in Joint Doctoral Program in Theology and Religious Studies at The University of Denver, where he is completing his second PhD, writing on ayahuasca and religious politics.