The editors of The New Polis have gathered below excerpts and summaries of some of the most significant reflections and observations that have been published to date on the long-term historical meaning of May 1968. Per an earlier call, we invite readers to send us their own take, whether it be in the form of quick takes or longer essays. Please send all queries to Roger Green, general editor.

From the blog of Thomas Piketty, author of the best-selling book Capital in the Twenty-First Century:

Should we burn May ’68? Critics claim that the spirit of May ’68 has contributed to the rise of individualism, even to ultra-liberalism. In truth, these assertions do not stand up to close scrutiny. On the contrary, the May ’68 Movement was the start of a historical period of considerable reduction in social inequalities in France which ran out of steam later for quite different reasons…

After Piketty’s book first appeared in 2013, the international magazine The Economist hailed him as “the modern Marx.” Piketty’s basic thesis has been that the natural tendency of market economies is toward the concentration of wealth in the hands of fewer and fewer. It was only during the period of militant socialism from 1914 to 1970 that this trend was reversed. Piketty’s book is not, however, a Marxist polemic, but is shot through with statistics, tables, and a host of various methods of quantitative analysis spanning the last three centuries to make its case. Piketty’s “solution” to growing economic inequality is a global “wealth tax,” a policy proposal The Economist derides, but is basically the same argument that Eric Posner and E. Glen Weyl make in their newly released book for Princeton University Press entitled Radical Markets: Uprooting Capitalism and Democracy for a Just Society.

From John Harris writing in The Guardian, “May 1968: the revolution retains its magnetic allure”:

We are now as far from the events of 1968 as the people involved were from the end of the first world war. Cliche has long since reduced much of what occurred to “student revolt”, but that hardly does these happenings justice, partly because it ignores the workers’ strikes that were just as central to what occurred during ’68 and the years that followed, but also because the phrase gets nowhere near the depth and breadth of what young people were rebelling against, not least in France…

The author points out that May 1968 has become more an iconic cultural event than a genuine window into the social and economic history of the last half century. For example, while ignoring the importance of the workers strikes that gave the uprising real heft beyond the university student protests that have now captured most of our attention, the commentators on May ’68. He notes how fashionable clothing manufacturers have been just as wont to enshrine the memory of these incidents as political theorists and historians.

From Alissa J. Rubin in The New York Times:

Today it is hard to imagine a Western country completely engulfed by a social upheaval, but that is what happened in May 1968 in France. It is hard to find any Frenchman or woman born before 1960 who does not have a vivid and personal recollection of that month.

About six weeks before the protests erupted France’s leading newspaper Le Monde had editorialized that the country was “too bored” to imitate the revolutionary upheavals that were happening in other parts of the world. Thus the events of May 1968 caught the whole country by surprise. It was not just an insurrection by one repressed, angry segment of society. It was a mass protest that cut across all classes and iterations of French identity. There is no French person alive today, born before 1968, who does not share some striking memory of those days, Rubin writes. What Nancy Fraser calls “the politics of recognition,” spawning such now familiar movements as women’s liberation and the demand for LGBT dignity and equality, all mark their beginnings, according to The Times, in May 1968. After the riots, things quickly returned to normal, but nothing paradoxically was ever the same again.

From Santiago Zabala writing in the English edition of Al Jazeera:

Over the last couple of months, many of us have been speculating on how French President Emmanuel Macron will commemorate the 50th anniversary of the May 1968 student uprisings. It seems unlikely that the young French president will choose to honour the revolutionary event in an appropriate manner.

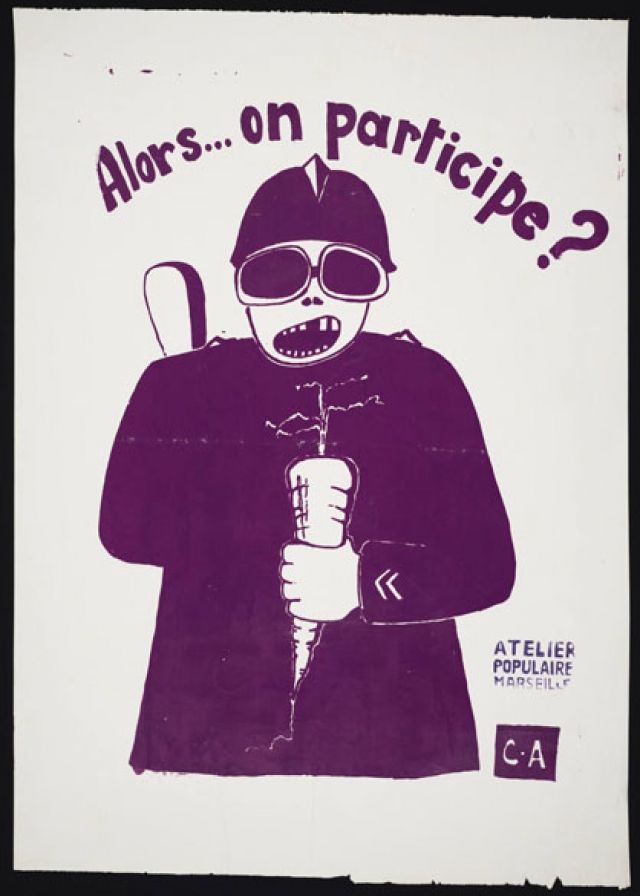

The May 1968 events, which took place not just in France but in such disparate countries as Pakistan, Mexico, Germany, and Italy (not to mention of course the United States), signaled the sudden collapse of the social and moral consensus buttressing the post-World War II industrial order. The agents behind these uprisings envisioned the creation of a whole new social order founded on personal and sexual freedom rather than nationalistic, ideological, or conformist regimentation. It is ironic that the spark that set off the conflagration was the refusal of a certain French university to allow any kind of male/female cohabitation in dormitory rooms, a standard that was rigidly the norm throughout Western societies. The rabid anti-authoritarian element in the student protests anticipated the sudden emergence of a new attitude toward government and political leadership. The new watchword was “participatory democracy.”

Zabala quotes, however, the famous pronouncement of the great French psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan to the members of the 1968 jacquerie: “what you aspire to as revolutionaries is a new master. You will get one.” That master perhaps today has a name – it is what we call post-Fordist “neoliberalism.”

From The West African Research Association at Boston University (WARC):

- the May ‘68 uprising at the University of Dakar was not simply a spillover from students’ unrests elsewhere, particularly in France;

- the time was ripe for the Senegalese population to openly voice their disagreement with the policies implemented by the Senghor government of the period;

- the Senegalese people were crying for more democracy;

- the country was officially independent but French influence was still too importantlocal entrepreneurship and economic ventures were stifled by French economic interests…

These foregoing were the conclusions of WARC members looking back to that period and its effect on the developing world. Many of whom fifty years later have become influential persons in West African politics.