In my previous post, I explored the distinction between the state of exception and Maurice Blanchot’s opening remarks from The Writing of the Disaster. I ended pondering some of Blanchot’s remarks on the disaster and forgetfulness with respect to Pan and “panic.” In this post, I want to more explicitly focus on some literary representations of Pan.

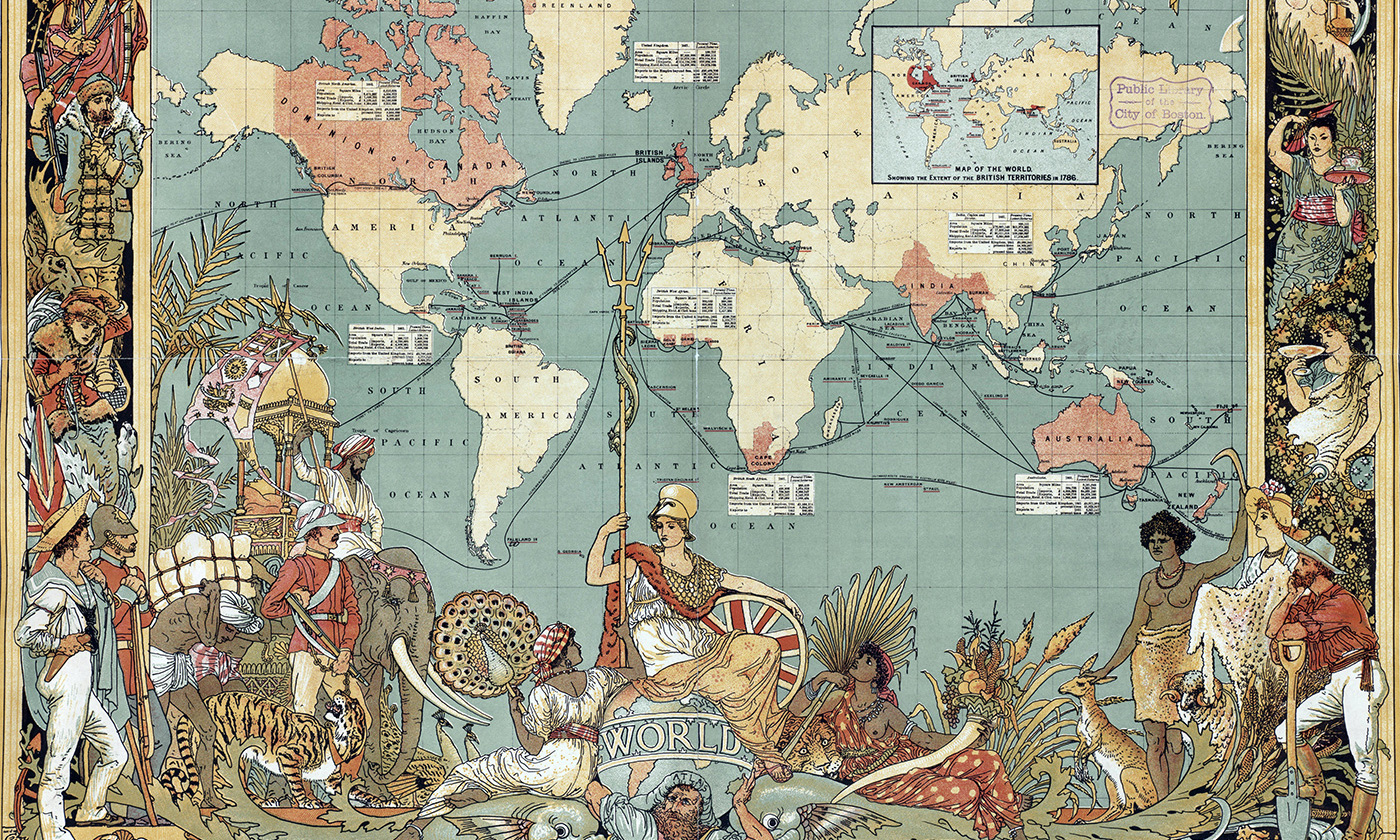

The god, goat-god, or demigod, Pan, makes many appearances in late Victorian and Edwardian literature. His most well-known appearances occur in children’s literature, where Pan signifies much more adult-oriented themes in Edwardian nostalgia, or homesickness, for Romantic youth. It is eerily fitting that this figure would be expressed during the period of the British Empire’s widest breadth.

Especially intriguing is the way Pan codes adult themes as they become associated with literature directed at children. Such literature, we know, is both produced and consumed by adults, making it an extraordinary genre expressing social desire. As an emergent genre during the period, it is quite interesting that many books regarded as children’s “classics” from “the golden age of children’s literature,” such as Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Tom Sawyer (1876), were not written with an audience of children in mind.

Robert Lewis Stevenson’s A Child’s Garden of Verses (1885) is often credited as one of the earliest attempts to write from an actual child’s perspective. “Bed in Summer” is a case in point.

In winter I get up at night

And dress by yellow candle-light. In summer, quite the other way,

I have to go to bed by day.

I have to go to bed and see

The birds still hopping on the tree,

Or hear the grown-up people’s feet

Still going past me in the street.

And does it not seem hard to you,

When all the sky is clear and blue,

And I should like so much to play,

To have to go to bed by day?

Stevenson’s attempt to catch the emotional concerns of an imagined child contrasts with the convention of an adult telling a child a story for entertainment or as a bedtime ritual. We are familiar with Charles Dodgson / Lewis Carroll’s relationship with the actual Alice Liddell, who inspired Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, for example. Similarly, J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan grew out of his relationship with the Llewelyn Davies boys whose games inspired parts of the story.

In Jacqueline Rose’s classic critique of children’s literature, The Case of Peter Pan or the Impossibility of Children’s Fiction, Rose famously says, “Peter Pan is a front – a cover not as concealer but as vehicle – for what is most unsettling and uncertain about the relationships between adults and children. It shows innocence not as a property of childhood but as a portion of adult desire” (xii). This can be a difficult lesson for children’s literature students to learn.

In my children’s literature courses, my students are quick to identify the blatant racism and sexism in J. M. Barrie’s Peter Pan. They recognize and critique the narrowly gendered role Wendy is “forced” into and the inadequacies of the middleclass nuclear family, though more rarely do they critique the “failed” masculinity of Mr. Darling / Hook – an Oedipal dramatization of which Freud could only have dreamed.

Peter’s Neverland is not just the “I won’t grow up” space of resistant childhood, an echo of Freud’s theory of unconscious. Instead, I will argue that it is one instance of a larger confinement of folk religion to the prison of the late Victorian and Edwardian mind, housed in the locked construct of childhood.

Seeing Pan as merely a “front” for sexual (or more broadly libidinous) desire, while partially correct, is also limiting. A shadow-text of cultural oppression is at work in the play and in the figure of Pan generally during the period, deeper than the obvious ones my students pick up on with gender and the racist and colonialist tropes accompanying Tiger-lily and American Indians.

There is a specifically political-theological shadow I want to address, part of a deep eurochristian framing. This is a longstanding tension between a declining “official” and perhaps Anglican Christianity and more “enchanted” folk beliefs. The classical figure of Pan’s frequent emergence in late Victorian and Edwardian literature dramatizes this tension, and tracking it requires attention to psychological, mythological, and historical methods to articulate how the shadow text at work with Pan in Edwardian literature is territorialized in national and international fantasies of empire.

While my students can see the gendered constraints Edwardian places on Wendy in particular, they are more reluctant to read the expression of Wendy’s desire for Peter, and Peter’s masculine failure (in a heterosexual frame), as sexually libidinous. Barrie regularly plays language games, such as substituting a thimble for a kiss. Peter’s inability to tell the difference between a thimble and a kiss signifies his own amnesia about his mother.

Playfully more expansive than sexuality alone, Peter’s arrested development becomes a site of intergenerational structures of delay and anticipation, and in that sense desire in the play — as well as its novel form, Peter and Wendy — does indeed code a nuclear family’s procreative potential. It simultaneously expresses a cosmology of empire and arguably concerns over colonialism as a static and unsustainable desire.

Although one might read an implicit dissent in the play / novel, the celebration of Peter Pan as a children’s “classic” often acts in problematic ways, taking the cosmology of empire in the play as uncritically as thinking that Peter is a “good” character when he is a rather nasty liminal character who fittingly expresses the characteristics of Pan.

This of course requires us, following Rose, to see that the genre we call children’s literature is certainly not always for or about children. Paralleling this, students often need to get over their resistance to reading the explicitly sexual aspects of the literature while simultaneously not simply reducing all desire to a crassly determined notion of “sex.” When such bourgeois frames are superimposed onto literature, they merely express nostalgia for romantic notions of childhood innocence.

The same resistance I see in students who refuse to read child characters as expressing sexual desire in Peter Pan also occurs when we read Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden. Here again, the Pan figure, who is occupied in the character of Dickon, plays with Mary, lustily plunging a knife into the rich soil of their secluded garden. It is not a matter of one single author’s coded perversions. Something larger is at work.

Undoubtedly, the resistance I see with students is expressive of middle class values, of their own performance of what Perry Nodelman calls the “shadow text.” Readers interestingly express these values more prominently in my children’s literature courses than in, say, American literature courses. As many literary critics note, the genre intellectually ghettoizes texts that have important things to teach us historically and culturally about how children and fairies occupy very complex cultural desires.

Such generic assumptions often prevent readers from understanding historical, scholarly claims like those Carole Silver makes in Strange and Secret Peoples: Fairies and Victorian Consciousnes. Silver says, “The lost child itself assumes symbolic significance as it becomes a sort of paradigm for Victorian concerns with both the loss of innocence and the loss of self” (72). As Silver notes, in folklore studies at least since the Brothers Grimm, “fairies stole human offspring to improve their breed,” which led later Victorian euhemerist folklorists to suppose that there were historical roots in the stealing of children between Saxons and Celts latent in fairy stories.

Without necessarily agreeing with the euhemerist perspective, how might we read Wendy Darling’s sexualized relationship with Peter, protected by a “kiss” in the form of a “thimble” in light of this? Euhemerism — the idea that at their core, myths code original historical events — saturates eurochristian phantasy structures and reading desires. Peter’s inability to enter the symbolic order or “grow up” prevents him from engaging with Wendy as a wife and partner instead of as a mother and prize. If he were to do so, it would also mark a potential end to the fairy-folk population, as Tinker Bell well knows.

Peter’s “failed” sexuality leaves Wendy unfulfilled at home with the other Lost Boys in Neverland, but Wendy, the Edwardian child (and Barrie’s own mother fantasy), cannot rejuvenate the fairy population except in the transfer of faith to a play, an audience, and the clapping of hands. Here, the tragedy of modern progress is placed on the young woman who takes on the responsibility of growing up and marrying a Mr. Darling / Hook who gives her children but little security or maturity.

It becomes a choice between “growing up” and imagination. Wendy is surrounded by incapable male figures, including the lost Peter, who in Barrie’s literary imagination amalgamated his own childhood attempts to replace his dead older brother in order to receive attention from his grieving mother (Birkin 5). Yet eurochristian phantasies of “development” are embodied in Peter’s arrested development.

For the critic Perry Nodelman, in his book, The Hidden Adult: Defining Children’s Literature, a shadow text is the often-unacknowledged cultural situation framing the text. He is importantly in dialogue with Jacqueline Rose’s The Case of Peter Pan. Against Rose, Nodelman not only sees the possibility for the genre of children’s literature, he also recognizes the complex expectations texts presented as children’s literature have for child readers.

According to Nodelman, when people in western culture think of reading to a child, the child is strangely expected to understand that the protagonist is supposed to be her, perform that recognition for the adult chaperone of the story, and then immediately dissociate from the reading / being-read-to situation in order to see why she ought not to be overly curious like a monkey named George or a blockhead named Pinocchio who repeats the same follies again and again. This is quite a lot of complex cognitive work to expect from young people.

David Rudd has taken issue with Nodelman in his book, Reading the Child in Children’s Literature. He simultaneously agrees and disagrees with Rose’s contention that children’s fiction (at least) is impossible. Rudd argues that Nodelman risks colonizing the child’s reading, even in his theory. Rudd instead offers in defense a Lacanian reading of Peter Pan and his extensions in film such as The Lost Boys (1987), and Hook (1991).

Rudd argues that the figure of Peter Pan, in refusing to grow up, refuses to enter Lacan’s symbolic order, the order of language itself. In this reading the literary character of Pan represents the linguistic excess of the story itself, and I am building on it in suggesting that we as readers ought to transcend Barrie’s texts, dropping the weight of Peter for the moment, and focusing on the broader literary significance of Pan for the period.

Rudd’s psychoanalytic reading de-emphasizes historical context in favor of the ludic qualities present in the literary figure. Thus he resists the kneejerk moralizing my undergraduates are so keen to mark which would deem the text “inappropriate.” He is not alone among scholars in doing so. In a fairly recent article from Children’s Literature Association Quarterly titled, “Other Maps Showing Through — The Liminal Identities of Neverland,” Paul Fox argues against overly reductive postcolonial readings of Barrie’s Peter and Wendy. In Fox’s reading, the collective unconscious space of Neverland offers a morality of imaginative potentialities. He says,

morality in Neverland is lived, not imposed, a contingent pattern of social relations rather than societally binding. And the island’s continuing potential for creating those identities beyond the stereotypes of the real can exist for as long as there are mothers with children, or readers with imaginations fertile enough to chart the unexplored. (266)

At work in Fox’s claim is something similar to the film, Neverland (2003), where Barrie’s wonderful imagination holds precedence on his literary legacy. Such triumphant readings, however, risk obscuring the inequities of the liberal imagination by fetishizing its creative and innovative potential at the expense of marginalized beliefs and practices and re-inscribing romantic notions of childhood.

In other words, both Rudd and Fox are optimistic about the unfixed nature of Pan and his resistance to entering the symbolic order, yet no matter how post-post colonial or poststructural their attempts are, they display an optimism worthy of John Stuart Mill’s Utilitarianism and liberalism’s ultimate ability to “include” all marginalized perspectives, even if they had to be oppressed for a certain period.

Mill had a high regard for Reverend John Llewelyn Davies, grandfather to Peter Llewelyn Davies, the namesake for Peter Pan. The Reverend died in 1916, and his obituary makes no reference to his grandchildren but only to his son who died young of a “lingering illness” (“The Times”). J. M. Barrie took care not only of the Llewelyn Davies boys and their mother after Arthur Llewelyn Davies passed away, he also paid for Arthur’s medical bills and visited his bedside and Arthur had written his father as he was dying of his appreciation for Barrie’s support (Birkin 145).

It’s unclear whether or not the Reverend took interest in Barrie’s work, though nine-year-old Peter Llewelyn Davies wrote to him about the play just before his 80th birthday in 1906 and included a program. Silver writes that “all who asserted that fairies were actual rather than imaginary did so with a sense that their reality was a protest against sterile rationality, evidence that the material and utilitarian were not the sole rulers of the world” (40-41).

Reverend Davies’ politics, however, were clear. He had delivered “in Queen Victoria’s presence a blistering attack on Imperialism from the pulpit at Windsor” (Birkin 46), and this got him removed to remote Westmoreland, where he continued to express radical political views. It is clear from Reverend Davies’ Hulsean Lectures delivered at Cambridge in 1890 entitled, “Order and Growth, as Involved in the Spiritual Constitution of Human Society,” that he takes a stand similar to the emergent Social Gospel movement while incorporating Darwin’s notions. This primarily Protestant movement prioritized disenchanted views of Christian doctrine in line with 19th century socialism.

Emerging alongside the Protestant social gospel was an interest in pagans and fairies during the late Victorian and Edwardian that would have likely implied a number of views. First there was the view that such a person believed fairies were spirit (a religious view). Others believed fairies were matter (post-Darwin scientism’s view). Still others that they were psychically evolved visions (Silver 37-51). Any of these beliefs might sit uncomfortably with a well-to-do mainstream eurochristian perspective during the period.

Barrie’s views on religion are seldom discussed, though his first novel deals with the strict Presbyterian sect of “Auld Lichts” to which his grandfather belonged. Fairies might signify being “low born” and even “Irish” to some Victorians, as is evident in Kingsly’s Water Babies (1863), or simian as in Dickens’s Bleak House (1852), or merely “betwixt and between” as Barrie describes them in Little White Bird (1902) (Silver 80). The interstitial spaces of fairies have allowed much for critics like Rudd and Fox, who enjoy the ludic nature of Pan’s occupying liminal spaces.

They are important for less binary oriented gender critiques as well. In Kathryn Bond Stockton’s The Queer Child, or Growing Sideways in the Twentieth Century, Stockton argues for the “queerness” of all children based on social reluctance to see them as sexual beings. We might then call Peter Pan “queer” in his very resistance to enter the sexually symbolic order, with his retention of razor-sharp baby teeth and his ignorance of kisses while simultaneously strutting about in cocky display.

Jacqueline Rose is certainly aware of this potential in her remarks on the first overtly lesbian production of the play (where a female actor had traditionally played Peter). While I do believe a reading of queerness as resistance to a gendered dynamic is useful in a character like Peter, I also believe that, historically, the figure of Pan is clearly gendered as a grossly masculinized “savior” for late Victorian and Edwardian culture, yet importantly as savior who fails.

To resist this context in favor of Pan’s inherent resistance to enter the symbolic order is again to ignore an important shadow-text of the cultural moment in the early twentieth century. I do not reject, but rather seek to build upon readings intrigued by Pan’s ludic qualities. The moment of dissent in the play may very well occur by reading Peter not as hero to the liberal imagination but as the arrested development of colonialism itself, so if we’re too quick to simply praise the queerness of the character we’re likely to forget that that notion of queerness may harbor its own liberal ideology, which would be quite antithetical to what classic queer theory attempts to do (at least in my reading).

Our reading strategies come with their own embedded politics, just as Pan maintains multivalent significations within the late Victorian and Edwardian periods. In this instance, we would do well to attend to the words of Stuart Hall as he reflected in his later years on the project of Cultural Studies with respect to its “linguistic turn”:

There’s always something decentered about the medium of culture, about language, textuality, and signification, which always escapes and evades the attempt to link it, directly and immediately, with other structures. And yet, at the same time, the shadow, the imprint, the trace, of those other formations, of the intertextuality of texts in their institutional positions, of texts as sources of power, of textuality as a site of representation and resistance, all of those questions can never be erased from Cultural Studies. (82)

Hall asks us to live in the space of tension between textuality and “the world,” where situations demand interventions: “culture will always work through its textualities – and at the same time that textuality is never enough.”

In Part 2 of this series of posts, I will continue to look at the figure of Pan in the broader Edwardian landscape, specifically in Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows, Burnett’s The Secret Garden, and E.M. Forster’s “The Story of a Panic.” I will continue to argue that, as a pagan figure, Pan manifests an Edwardian desire to re-enchant England as a critique of the British Empire while also remaining intellectually and culturally elitist. As a figure, his ability to code dissent and critique — like those who express the desire for dissent without understanding the deeper histories of oppression — may not be dissent at all, but rather another attempt to re-enchant empire.

Roger Green is general editor of The New Polis and a Senior Lecturer in the English Department at Metropolitan State University of Denver. He is the author of A Transatlantic Political Theology of Psychedelic Aesthetics: Enchanted Citizens.