In my previous post, I argued that as a pagan figure, Pan manifests an Edwardian desire to re-enchant England as a critique of the British Empire while also remaining intellectually and culturally elitist. Here I continue to analyze the figure across various texts.

J.M. Barrie’s Peter Pan famously comments on the growing disenchantment of children via a lack of belief in faeries. At times, our contemporary nostalgia for “golden age” children’s literature eclipses what was a late Victorian nostalgia for enchantment itself. By ‘enchantment’ here, I am only partially signaling Max Weber’s famous characterization of modern life as ‘disenchanted’.

While recently scholars have been rethinking secularism (or at least self-congratulatory liberal narratives that see religion as signaling something archaic), it is also true that especially in England during the late nineteenth century something like disenchantment had occurred. In that cultural milieu, the “scientific” study of religion, along with the “world religions” models such as Friedrich Max Müller’s developed.

In the late nineteenth-century context, non-Christian forms of enchantment coded cultural dissent. Romanticism had lamented a cold rationalism that seemed devoid of ‘spirit.’ Darwinism and utilitarian liberalism had seen itself up as a pinnacle of scientific thought while implicitly coding the Englishman as the inheritor and model of the project of “civilization.”

In the late Victorian era, there also persisted a nostalgia specifically for a kind of enchantment fueled by a nationalistic force that hearkened back to Romanticism. This force would blend privilege and mystification particularly in “developmental” notions of culture as presented in works such as E. B. Tylor’s Primitive Culture (1871).

Romanticism had lamented modern “man’s” alienation from nature, but the emergence of anthropology and notions of spiritism, which had sought to fuse emergent scientific discoveries with spiritual beliefs, signaled that the Victorian “official” (Anglican) Christianity remained equally ambivalent about romantic nostalgia for enchentment. Pan shows up as an embodiment of these contradictory impulses. Take, for example, Elizabeth Barrett Browning’s musings on Pan from “A Musical Instrument” (1860).

VI.

Sweet, sweet, sweet, O Pan !

Piercing sweet by the river !

Blinding sweet, O great god Pan !

The sun on the hill forgot to die,

And the lilies revived, and the dragon-fly

Came back to dream on the river.

VII.

Yet half a beast is the great god Pan,

To laugh as he sits by the river,

Making a poet out of a man:

The true gods sigh for the cost and pain, —

For the reed which grows nevermore again

As a reed with the reeds in the river.

Barrett Browning’s poem opens with a description of the creative destruction caused by Pan plucking a reed and fashioning his pipe. Here we glimpse the process of alienation from a state of nature

There is a price for creativity — and Barrett Browning knows this intimately as both a poet and woman — in the obviously mixed-up gender dynamics that would not fully acknowledge a woman’s capability as a “creator” in the masculine-saturated milieu of nineteenth-century poetry. Here alienation from a “state of nature” is a detached and alienated masculinity.

Ironically, however, the coded sexual desire is blocked by this alienated and masculine creativity, fused with a “progressive” account of civilization. Seduced by “civilization,” for Barrett Browning the “true gods sigh for the cost and pain.” Her “true gods” retain a bit of christian humanism even while we might read her critique as particularly gendered.

Frankly, for the Greeks, the gods could care less about human suffering. As Heidegger would later intimate, the very structure of “care” is embodied in a being-toward-death, an anxiety that is entirely aware of its finitude yet unaware of the precise moment of its end. Heidegger’s philosophy in this way embodied a culmination of the eurochristian and the europagan deep cognitive structures, which were synthesized as, “I might as well take what I can get while I can get it,” a peculiar reformulation of the Roman “Seize the day!”

We do not normally think of Heidegger as a “pioneer” philosopher. The deep cognitive structures — idealized cognitive models or ICMs as George Lakoff and Steven T. Newcomb (Shawnee / Lenape) put it — reiterate their arrogance through a kind of “advancement” that erases as it moves forward. While it is correct to associate the persistence of eurochristian Romanticism with American Exceptionalism, as Tink Tinker has done, it is also important to “cross the pond” to see various roots of eurochristian (white) supremacy in “progress” narratives.

This summer more than 80% of so-called “progressives” supporting moveon.org embrace an entirely status-quo Joe Biden simply to remove the current neo-fascist regime. Yet many are largely unaware of their own commitment to white supremacy, simply so they can feel good about themselves for removing a moron only elected because globally over the past fifty years the world has “swung right.” It is easy enough to call out neo-fascists and police-abusers — and it remains necessary to do that — but my focus here is on culturally valued narratives less explicitly tied to white supremacy and yet nevertheless underwritten by the impulse to superiority.

Returning to the late Victorian moment, the early William Butler Yeats combined a quasi-Romantic critique of modern alienation with an intellectual inquiry in Fairy and Folk Tales of the Irish Peasantry (1888). Less “scientific” than Tylor, Yeats saw folkloric studies and anthropology as a social critique that could provide a degree of dissent against Tylor’s schema of human “development.” This, like the Scottish J.M. Barrie’s combined use of fairies and Pan, exemplified a “re-enchanted” critique of empire.

Yet to delight only in Romantic readings of Barrie’s intentional re-enchantment of fairies by having children in the audience clap their hands, thus prolonging the innocence of childhood, misses the exigence of this gesture in the Edwardian period, when feelings about the British Empire and nationalism were more vexed than the early 1800s. The figure of Pan, who is superimposed on the changeling of Peter and who converses with fairies in Neverland, helps us address the ways Edwardian literature displays suspicious feelings about land and empire.

The Edwardian situation can be briefly dramatized in the characters of Kenneth Grahame’s Wind in the Willows. In the book, the humble and middle-class Mole leave’s his spring-cleaning to encounter a worldlier water rat. From him the Mole learns the pleasures of leisure. The two friends meet the more learned badger while distinguishing themselves from the “lower” stoats and weasels.

The three relatively middle-class friends get together and attempt multiple interventions to restrain the excessive and aristocratic Mr. Toad –“ the best of animals” – whose fascination with modern things leads him from one wasteful catastrophe to another. While Mr. Toad is imprisoned, the estate of Toad hall is overcome by the lowly weasels and must be conquered by the respectably middle class friends, just as the Greeks conquered Troy, in order to found a new civilization.

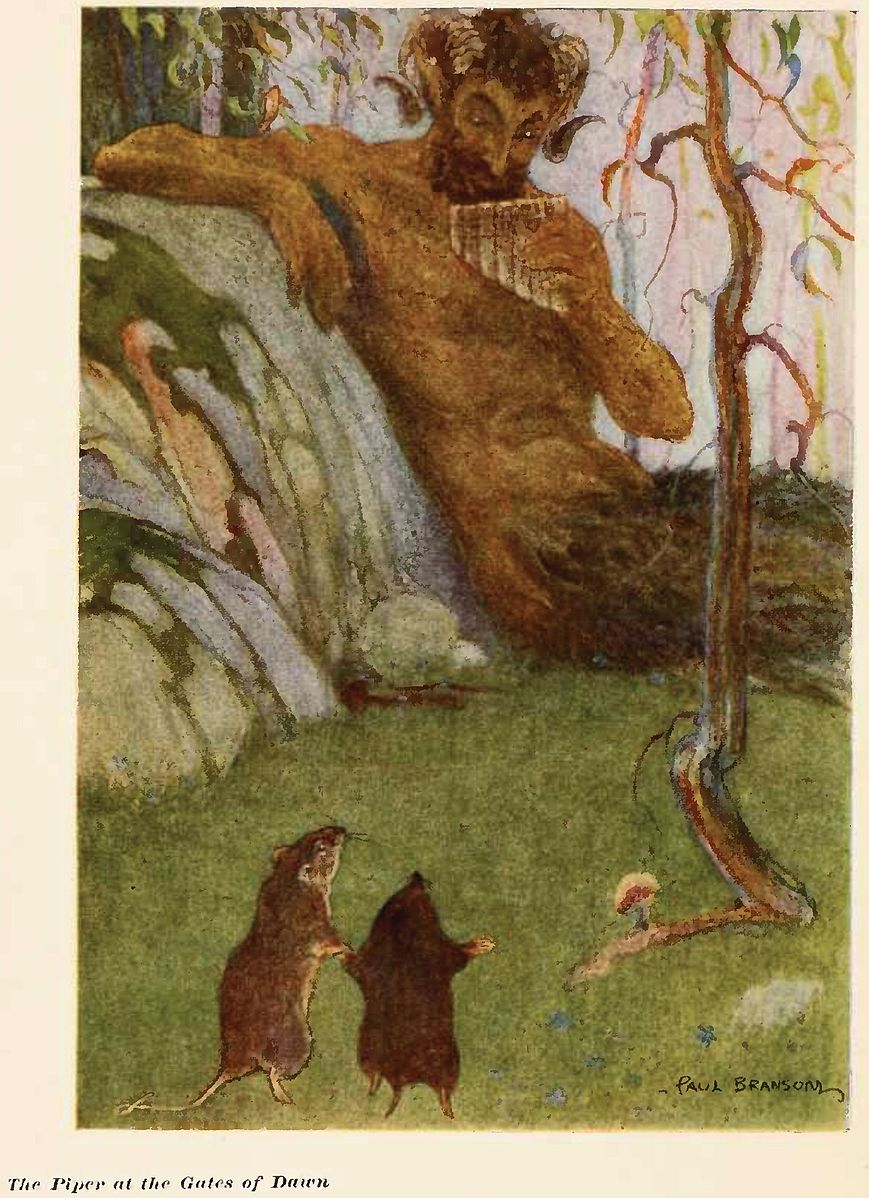

Pan’s appearance in Wind in the Willows is especially dark. He appears in chapter nine of the book, perhaps now more famously known today as the title of Pink Floyd’s album, “The Piper at the Gates of Dawn.” As a classical figure, Pan has various origin stories, most commonly as the son of Hermes, as attested to in the Homeric hymns. In others, Pan is the demi-god son of Apollo, Dionysus, or the older Pytho, from whom the Pythian priestesses who serve Apollo get their name. Undoubtedly, these multiple origins enable his ability to hold contradictions.

The serpent goddess of the temple at Delphi, who was later slain by Apollo, is a fertility deity of the field, and there are numerous syncretic references in mysteries cults. In Sir James Frazer’s famous euhemerist work of the period, The Golden Bough (1890), Pan is described with reference to the scapegoat sacrifice and the flogging of genitals with the leaves of squills – a marshy plant related to the lily. This is not as punishment but as purification:

we must recognize in him a representative of the creative and fertilizing god of vegetation. The representative of the god was annually slain for the purpose […] of maintaining the divine life in perpetual vigour, untainted by the weaknesses of age; and before he was put to death it was not unnatural to stimulate his reproductive powers in order that these might be transmitted in full activity to his successor, the new god or new embodiment of the old god, who was doubtless supposed immediately to take the part of the slain. (Frazer 672)

While Ernst Kantorowicz has traced the idea of The King’s Two Bodies to medieval christianity, we might also consider how the ambiguity surrounding Pan’s creation-destruction myth on the surface offers a critique of empire while simultaneously offering a deeper persistence, a “spiritual body” here articulated as a deep cognitive framing as a tool of conservation.

In the passage above, Frazer is especially concerned to point out that earlier mythologists who read the Egyptian god Osiris and Pan as formulations of a sun god are wrong. Leaving aside, for the moment, the complexity of later twentieth-century critiques of Frazer’s ultimate thesis, his thinking here portrays a correlation between folk religion and primitivism characteristic of nineteenth century mythology and anthropology which over-determined evolutionary accounts of culture and religion.

Nevertheless, there is also something particularly territorialized about Pan. In the context of England in the 1890s, the turn toward pagan creatures and talking animals masked an ambivalence, not just about empire but of the coming royal succession as Queen Victoria was growing older. A purely disenchanted view of spirituality glosses over the nuances at work in enchanted literature and the political role that belief in fairies played with respect to critiques of empire.

On the one hand, the decline of Christianity opened less oppressed inquiry into pagan religions; on the other hand, references to the classical literature remained the intellectual ground of elites who have had enough training to decipher literary allusions to Greek and Roman literature. To exemplify, let me now turn to Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows (1908), Frances Hodgson Burnett’s Secret Garden (1911), and E. M. Forster’s “The Story of a Panic” (1904).

In “The Piper at the Gates of Dawn” chapter of The Wind in the Willows, Ratty and Mole have embarked into the ambiguous liminalities of twilight in search of young Portly, a missing otter. As the narrator says, “[t]he Willow-Wren was twittering his thin little song, hidden himself in the dark selvedge of the riverbank” (116). Ratty has returned to Mole from dinner with Otter, who is worried about Portly, his son who has gone missing. Mole characterizes Portly as adventurous, “always straying off and getting lost, and turning up again” (117).

Portly has been missing for a few days, and the characters show a typical Victorian and Edwardian concern for the child. Earlier in the text, the children are depicted as poor in relation with the educated and stately Badger. Ratty shows particular concern about humans preying on animals, mentioning “traps and things – you know” (118). Mole in his middle-class need for action says, “I simply can’t go and turn in, and go to sleep, and do nothing, even though there doesn’t seem to be anything to be done […] anyhow, it will be better than doing nothing” (119). And so the two seek to find and protect the lost animal-child.

As the two companions set out in Ratty’s boat, we notice a marked transition of station with respect to earlier in the novel. Mole, who had never been on a boat before at the outset of the novel, now steers while the accomplished Water Rat rows (120). The sky shifts; the moon appears above. The narrator tells us: “Then a change began to slowly declare itself” (121). The aesthetically sensitive Rat, cultivated in his tastes, begins to be hypnotized by beautiful music. As he phases in and out of his ability to hear it, he tells Mole, “it has roused a longing in me that is pain, and nothing seems worth while but just to hear that sound once more and go on listening to it for ever. No! There it is again!” (122-3).

Under the influence of his cultivated friend, Mole begins to hear it too. They approach an island “in midmost of the stream” (123). It contains “Nature’s own orchard trees” (124). Rat says, “This is the place of my dreamsong” (124). As Pan appears lulling above the sleeping Portly, the language becomes allegorical. Mole asks if Rat is afraid: “Afraid?” murmured the Rat, his eyes shining with unalterable love. “Afraid! Of Him? O, never, never! And yet – and yet – O, mole, I am afraid!” […] “Then the two animals, crouching to the earth bowed their heads and did worship” (126). Here is a cultivated pagan ceremony.

The danger of Pan is of course that in the beauty of his pipes, all memory and desire is lost, even the desire to live, the psychic Lacanian desire to participate in the substitution of the symbolic order. But the two friends are able to rescue the sleeping Otter from the enchanted weir, losing their memories of Pan as they paddle away.

The image of Pan in Grahame’s work is primarily classical in form and aspect. The successful alliance of the well-to-do, middle class and the more refined upper class are able to keep the aristocratic prodigal sons like Toad in check, but Pan lurks in the forests waiting to lull lost children away. As Rat tells Mole, invoking a darker tradition of literary encounters with Pan, “I feel as if I had been through something very exciting and terrible, and it was just over; and yet nothing particular has happened” (129). And so they return to the tranquil order of quaint Edwardian England.

Grahame’s ultimately rather innocuous presentation of Pan is indicative of a shift in literary usage of Pan between the Victorians and the Romantics, a shift largely in debt to Elizabeth Barrett Browning who was among the first to cast Pan as alluring rather than horrifying. As Patricia Merivale points out in Pan the Goat-God, Browning, in a letter to John Kenyon in 1843, says,

Certainly I would rather be a pagan whose religion was actual, earnest, continual…than I would be a Christian who, from whatever motive, shrank from hearing or uttering the name of Christ out of a ‘church’ …What pagan poet ever thought of casting his gods out of his poetry? (in Merivale 83)

As the benevolent Pan emerges throughout the 19th century, Pan becomes a figure, rather than the feeling of panic. This “revival” of Pan put him into contestation with the figure of a “dying” Christ, enabling a widespread ability for writers to casually allude to him and expect readers to understand Pan “as a useful symbol for cultural history, to be equated with whatever the author thinks of as typically Greek” (115).

Merivale quips: “The benevolent Pan in prose fiction was simply the logical development of the whole pastoral, Arcadian tradition in English literature – its final, if not its finest, fruit” (134). This characterization of the benevolent Pan causes Merivale to exclude in-depth discussion of Peter Pan, which she says, “owes much more . . . to some archetypal figure like Sidney’s “shepherd who piped as if he would never grow old, or Blake’s “Piper,” than he does to any version of Pan” (152). But it is in this very transfer from panic to pastoral, from feeling to land that I am interested.

As with Peter Pan, Merivale’s otherwise brilliant survey lacks specific discussion of Frances Hodgson Burnett’s The Secret Garden, where Pan shows up as a young country boy, Dickon, who helps re-enchant the over-privileged Mary quite contrary who has been orphaned from her rich and neglectful parents in India and returned to England to live with her uncle and his invalid son.

The Secret Garden, like The Wind in the Willows, offers a benevolent and pastoral Pan who nevertheless becomes a vehicle for critiquing the British Empire by focusing on autochthonous, domestic goodness. When Mary first sees Dickon, “a boy was sitting under a tree, with his back against it, playing a wooden pipe” (83). He has red cheeks and deep blue eyes and the animals are enraptured by his music. He speaks with a native pastoral accent that Mary wishes she could emulate and by the end of the novel does.

When Mary asks Dickon if he understands what animals say, he says yes and, “[s]ometimes I think p’raps I’m a bird, or a fox, or a rabbit, or a squirrel, or even a beetle, an’ I don’t know it” (86). Mary lures Dickon into her secret garden imaged as “some strange bird’s nest” (87), and Dickon remarks, “it is a queer, pretty place! It’s like as if a body was in a dream.” The garden is “th’ safest nestin’ place in Englan” (89). Dickon helps Mary cultivate her garden in sexualized language that embarrasses students:

“There’s lots o’ dead wood as ought to be cut out,” he said. “An’ there’s a lot o’ old wood, but it made some new last year. This here’s a new bit,” and he touched a shoot which looked brownish green instead of hard, dry gray. Mary touched it herself in an eager, reverent way.

“That one?” she said. “Is that one quite alive?”

Dickon curved his wide, smiling mouth.

“It’s as wick as you or me,” he said; and Mary remembered that Martha had told her that “wick” meant “alive” or “lively.”

“I’m glad it’s wick!” she cried out in her whisper. “I want them all to be wick. Let us go around the garden and count how many wick ones there are.”

She quite panted with eagerness, and Dickon was as eager as she was. (90)

Pointing out such thinly veiled sexual language is nothing new, but it often tests the interpretive boundaries in undergraduate readers. The point is not that such language is there but that ignoring it for decorum allows for misreading. Burnett’s language is not meant to be risqué so much as it is meant to insulate the children’s innocence and their potential to rejuvenate the land through a return to the “indigenous” folklore. Mary answers the question as to how her garden ought to grow a page later, swayed by Dickon:

“I wouldn’t want to make it look like a gardener’s garden, all clipped an’ spick an’ span, would you?” he said. “It’s nicer like this with things runnin’ wild, and swingin’ an’ catchin’ hold of each other.”

“Don’t let us make it tidy,” said Mary anxiously. “It wouldn’t seem like a secret garden if it was tidy. (93)

The secret enchants the garden, protecting it not only in youth but in the claiming of the fairy story. As Dickon says concerning the branches and flowers, “they’ll grow now like Jack’s bean-stalk” (92). As Mary departs from Dickon, she has similar emotions to those of Ratty and Mole leaving the piper: “Mary could scarcely bear to leave him. Suddenly it seemed as if he might be a sort of wood fairy who might be gone when she came into the garden again” (96). Like Barrie, Hodgson obfuscates a separation between Pan and fairies to assert an “indigenous” presence in the Yorkshire soil.

Pan’s presence then helps to re-invigorate a dying childhood for Edwardians by integrating an enchanted spiritual view, and as with much children’s literature acts as an insulated vehicle for progressive politics. More mainstream versions of disenchanted Protestantism obscure this, however.

In The Secret Garden, Mary and Dickon help to reinvigorate Colin, a young invalid boy neglected by his father who has been grieving for Colin’s dead mother. Through positive thinking, imagination and exposure to the secret garden he able to recuperate. Magic becomes a theme for what the garden and Dickon offer: “Even if it isn’t real Magic,” Colin said, “we can pretend it is. Something is there – something!” (205). Colin himself converts to a Christian Scientific and psychic-evolutionary view of magic: “I am sure there is Magic in everything, only we have not sense enough to get hold of it and make it do things for us – like electricity and horses and steam” (207).

After many a morning practicing magic in a “mystic circle under the plum tree” (222), Colin claims, “Now that I’m a real boy […] my legs and arms and all my body are so full of magic that I can’t keep them still” (228). Eventually Colin begins lecturing his friends on magic (233), prompting Dickon to teach him to sing the Doxology hymn’s verse from, “Awake, My Soul, and with the Sun” (236) and to reconcile his scientism with religion. Dickon’s mother then appears and reconciles magic with religion and its different names in different places. “I warrant they call it a different name I’ France an’ a different one I’ Germany Th’ same thing as sets th’ seeds swellin’ an’ the sun shinin’ made thee a well lad an’ it’s th’ Good Thing” (239-40).

This flattening of “religious” experience into a kind of “many mansions” universalism is a literary reflection of the thinking present in Tylor, Yeats, Müller, and Frazer. Thus in The Secret Garden the pagan figure of Pan enables a reconciliation between religion, science, and the indigenous land (Yorkshire). Both The Secret Garden and The Wind in the Willows seek a retreat from the idea of a British Empire to one of a more humble enchanted island, even if it is not as enchanted as Yeats’s Ireland or Barrie’s Scotland, but they do so by offering a quasi-romanticized “indigenous” subject able to heal modern alienation from local land and over-expanding policies of British Empire.

Yet in this phantasy structure there is nothing “indigenous,” or perhaps to be more precise, the texts work to code landed critiques within the United Kingdom while unabashedly relegating the “Indian” characters such as Tiger-lily in Peter Pan to a colonial romance. Similar to the rehabilitation of Toad in The Wind in the Willows, the spoiled brat, Mary Lennox, whose parents have died in India of cholera returns to England where she is “civilized” to an enchanted notion of “indigeneity.”

A final contrast to these two versions of Pan arises in E. M. Forster’s “Story of a Panic.” Forster’s story importantly takes place in Italy, not England, and it is told in the voice of a middle class English snob named Mr. Tytler, who is deprived of all aesthetic sensibility. In other words, Forster’s story critiques the empire by poking fun at performances of small-minded (and middle class) English supremacy outside the homeland. The story centers on a sickly and effeminate boy named Eustace, about fourteen years old.

I would not have minded so much if he had been a really studious boy, but he neither played hard nor worked hard. His favourite occupations were lounging on the terrace in an easy chair and loafing along the high road, with his feet shuffling up the dust and his shoulders stooping forward. Naturally enough, his features were pale, his chest contracted, and his muscles undeveloped. His aunts thought him delicate; what he really needed was discipline. (2)

In Eustace’s company is a dandyish aesthete named Leyland and Mr. Sandbach, who is described as follows.

Mr. Sandbach had also been there some time. He had held a curacy in the north of England, which he had been compelled to resign on account of ill-health, and while he was recruiting at Ravello he had taken in hand Eustace’s education—which was then sadly deficient—and was endeavouring to fit him for one of our great public schools. (1)

Sandbach, the unhealthy and retired curate, wants to train Eustace for what is implied to be a mediocre public education, one in which he would not likely be trained in the classics. As the company takes a walk in the woods, their discussion turns to Pan.

“I see no reason,” I observed politely, “to despise the gifts of Nature, because they are of value.”

It did not stop him. “It is no matter,” he went on, “we are all hopelessly steeped in vulgarity. I do not except myself. It is through us, and to our shame, that the Nereids have left the waters and the Oreads the mountains, that the woods no longer give shelter to Pan.”

“Pan!” cried Mr. Sandbach, his mellow voice filling the valley as if it had been a great green church, “Pan is dead. That is why the woods do not shelter him.” And he began to tell the striking story of the mariners who were sailing near the coast at the time of the birth of Christ, and three times heard a loud voice saying: “The great God Pan is dead.”

“Yes. The great God Pan is dead,” said Leyland. And he abandoned himself to that mock misery in which artistic people are so fond of indulging.

In Forster, we see here the typical dramatic set up for Pan as he most often appears during the period, as a figure of un-representable horror. In the woods, Eustace carves himself a whistle and blows on it, disturbing the others’ afternoon rest. Just after this a feeling of dread takes over everyone, and they find themselves running for their lives down the hill though they know nothing of what they’re running from.

When they gather their senses, they see no sign of Eustace and start slowly up the hill to see what had become of him. They find him lying down. As he comes to his senses, Tytler tells us,

“I caught sight of some goats’ footmarks in the moist earth beneath the trees.”

“Apparently you have had a visit from some goats,” I observed. “I had no idea they fed up here.”

Eustace laboriously got on to his feet and came to see; and when he saw the footmarks he lay down and rolled on them, as a dog rolls in dirt. (9)

Before they return to their lodgings, Eustace becomes more and more rambunctious.

Each time Eustace returned from the wood his spirits were higher. Once he came whooping down on us as a wild Indian, and another time he made believe to be a dog. The last time he came back with a poor dazed hare, too frightened to move, sitting on his arm. He was getting too uproarious, I thought; and we were all glad to leave the wood, and start upon the steep staircase path that leads down into Ravello. It was late and turning dark; and we made all the speed we could, Eustace scurrying in front of us like a goat. (11)

Eustace runs to speak to his Italian friend, Gennaro, who tells Eustace, “capito” – “I understand. Eustace becomes irritated about being confined indoors. The English adults take him to his room and he becomes delirious. In the night, Eustace escapes from his room and they lock him in. Gennaro tells them he will surely die. Tytler offers to pay Gennaro if he will help Eustace.

“I am an Englishman. The English always do what they promise.”

“That is true.” It is astonishing how the most dishonest of nations trust us. Indeed they often trust us more than we trust one another. (18)

When Genarro sets Eustace free, Tytler is outraged and demands his money back.

“The ten lire are mine,” he hissed back, in a scarcely audible voice. He clasped his hand over his breast to protect his ill-gotten gains, and, as he did so, he swayed forward and fell upon his face on the path. He had not broken any limbs, and a leap like that would never have killed an Englishman, for the drop was not great. But those miserable Italians have no stamina. Something had gone wrong inside him, and he was dead.

In Eustace we see a transfer of Pan’s power from older Italian man to the young English boy who is capable of more classical refinement than the dandyish aesthete, the retired curate, and the bull-headed middle class buffoon.

But what seems quite clear is how both paganism and notions of indigeneity in late Victorian and Edwardian literature have been reoccupied within an otherwise “progressive” critique of the British Empire coded as a humble “return to the land.” The underlying eurochristian impulse here is yet one of erasure and a recoding of romanticized innocence by way of “golden age” children’s literature.

It appears that the conception of innocence embodied in the romantic notion of childhood as it appeared when mothering and nursing became fashionable, just as the nursery in Peter Pan prefigures the “Baby industrial complex” of “Babies ‘R’ Us,” is a a cypher for cultural renewal and a return to “innocence” that claims a kind of “indigeneity” by way of an embrace of paganism and classicism. This impulse, just as it arises in New Thought, Christian Science, and Spiritism of the late nineteenth century does the cultural coding work that is a precursor to Anglo-appropriation of Native American (and other Indigenous) practices or “spiritualities.”

Here we see, clothed in the supposed innocence of “childhood,” an ongoing genocidal impulse. To the extent that our children grow up with these beloved tales, they are engrained to accept the demise of Indigenous Peoples just as much as they are to feel entitled to adopt whatever “spiritual” practices they themselves advance as the symbolic capital of “Indigenous” and “pagan” religions and “recovery projects.”

Roger Green is general editor of The New Polis and a Senior Lecturer in the English Department at Metropolitan State University of Denver. He is the author of A Transatlantic Political Theology of Psychedelic Aesthetics: Enchanted Citizens.